Politics ain’t bean-bag, as the old saying goes. But, by any measure, the 2016 presidential campaign has been a particularly bruising affair.

The electoral contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton has offered a riveting, if sometimes dispiriting, window into the ways gender and power operate within American culture, said Mary Ann Dzuback, chair and professor of women, gender and sexuality studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Students have been talking a lot about gender and representation,” Dzuback said. “How do the candidates carry themselves? How do they interact? How are they portrayed? And what do the media focus on?

“Almost no one comes out and says that we shouldn’t elect a woman president. But people do speak disparagingly of Clinton’s ambition, as if ambition were not a key criterion for political success. You don’t change the world — or do much of anything in life — without a clear sense of your own goals and abilities. And yet in Clinton’s case, ambition is seen as a negative because it’s not considered attractive for a woman to be ambitious.”

Conversely, Trump supporters have actively celebrated their candidate’s braggadocio. “Trump plays into gendered associations of what it means to be a successful man in our society — especially a successful, middle-class white man, and, even more particularly, a successful, middle-class white businessman.”

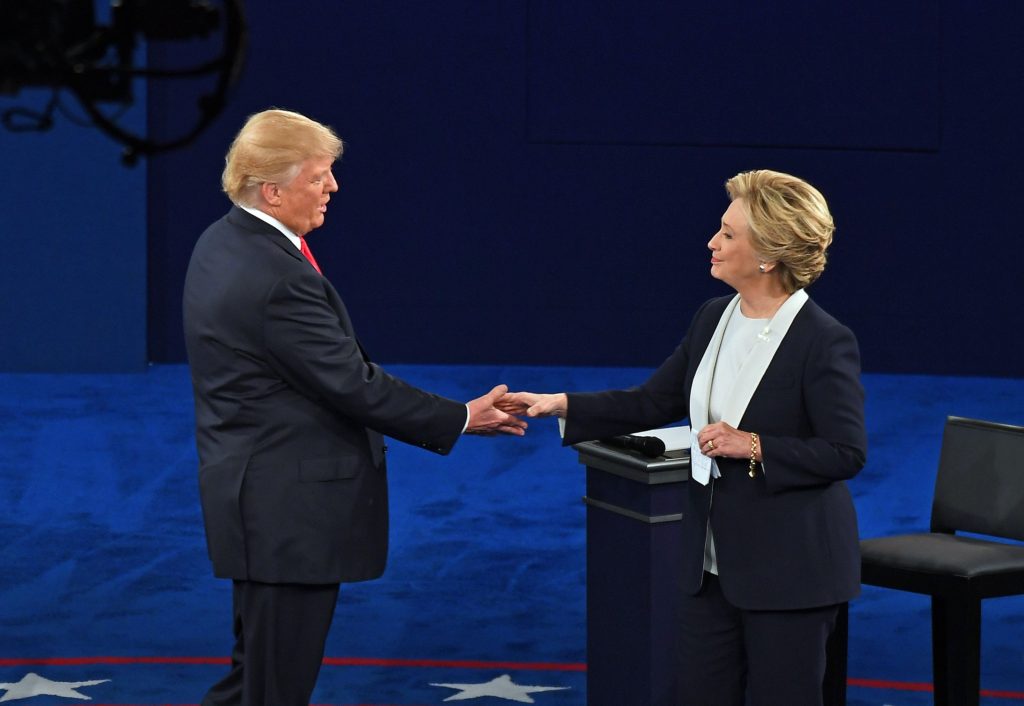

It is only in the past month, since the release hours before the second presidential debate of the Access Hollywood recordings — which Trump has dismissed as “locker room talk” — that “mainstream portrayals have grown more critical. The media have become much more willing to track how Trump became who he is, where he got his ideas of masculinity and power, and how those have developed over his lifetime.

“The debates were transformative,” Dzuback said. Though Clinton mostly stuck to substantive issues, she challenged her rival on precisely the grounds that he uses to define himself: his wealth, his combativeness, his treatment of women. “And Trump fell into the trap every time. There’s something so fragile there … He couldn’t take one poke without over-responding.

“It was very smart, very strategic,” Dzuback added. “Sometimes the best way to point out that someone is behaving badly is to step back and just let them talk.

“What remains to be seen is the extent to which the public discussion of sexual harassment — which has become more public than at almost any time since Anita Hill testified at the Senate in 1991 — will continue and perhaps lead to more lasting change in American workplaces, educational institutions, government offices and social spaces,” Dzuback concluded.