Skyler Field was having a terrible day. She was set to be discharged from the hospital after a routine hip surgery but fell while unattended in her room. The new injury nullifies the discharge plan that had been carefully crafted by her surgeon, nurse, occupational therapist and pharmacist, and now they must assess the patient and create a new one.

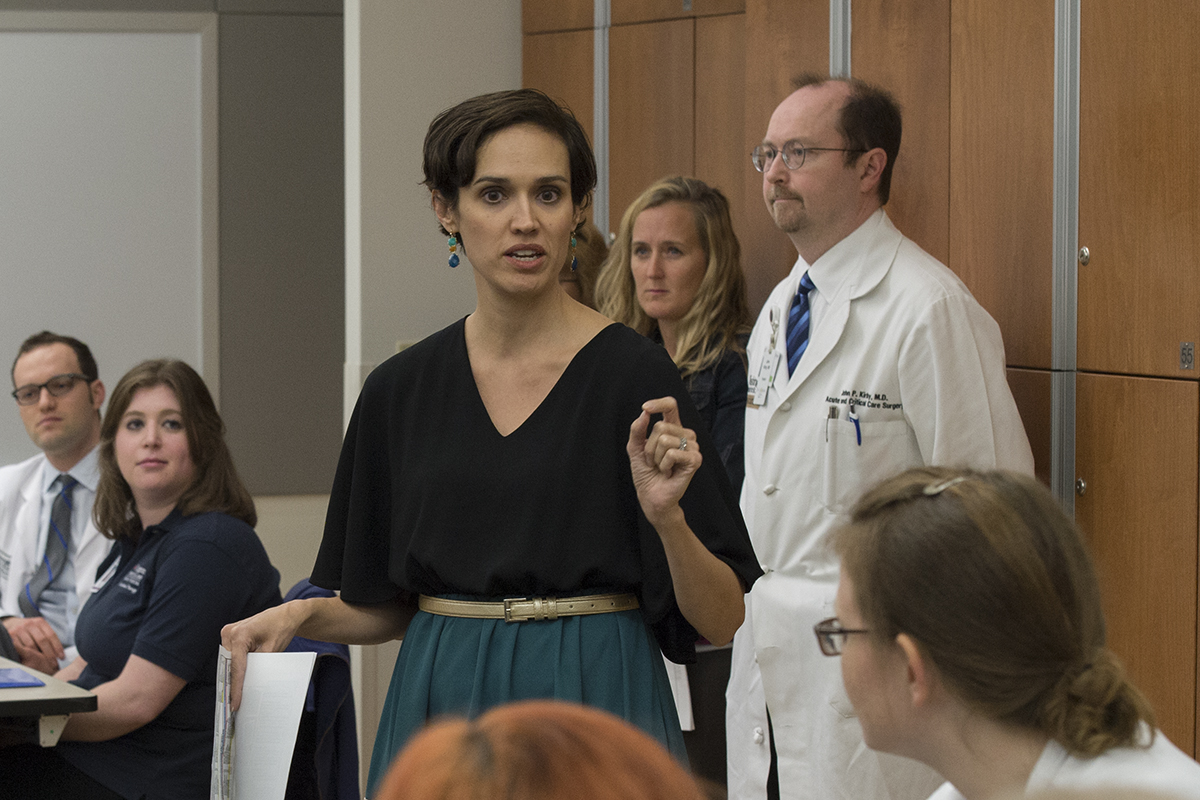

That was the simulation scenario confronting 110 students taking part in the new “Interprofessional Education” event, which draws its student participants from Washington University’s Department of Surgery and Program in Occupational Therapy in the School of Medicine, and from the neighboring Goldfarb School of Nursing at Barnes-Jewish College and St. Louis College of Pharmacy. They are all deep into their training, with some disciplines ready to graduate the next month.

“The skill of working together needs to be taught. Often, we have to start by developing a common language that all the disciplines understand.”

Dehra Glueck

“While working together in small interdisciplinary groups to care for the same patient, the students come to understand the differences in their knowledge and expertise, and how they complement one another in patient-centered care,” says Dehra Glueck, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and medical director of the standardized patient program in the School of Medicine. “The skill of working together needs to be taught. Often, we have to start by developing a common language that all the disciplines understand.”

Another goal is to alleviate apprehension the students may feel when transitioning from student to practicing clinician. “I hope they gain confidence and learn from mistakes in this supportive environment,” says Monica Perlmutter, OTD, assistant professor of occupational therapy in the School of Medicine.

Seven members of the red group stand outside Skyler’s simulation room door. For now, they’re still students, asking about one another’s schooling and post-graduation plans. One casually observes, “Every time we come in the room, we ask the same questions.” The statement hangs in the air. How will they remedy that during the exercise? A moment later, the instructors give the signal to begin, and the students’ demeanor changes. The students become practitioners.

With the precision of a military operation, the one-time-only class has been meticulously planned over the last year by representatives from each of the four programs. It’s the first time ever the simulation exercise has crossed so many institutional and disciplinary boundaries. It’s a welcome addition to a growing list of opportunities students have to develop their interprofessional skills, says Gloria Grice, PharmD, associate professor of pharmacy practice and interim director of the Office of Experiential Education at St. Louis College of Pharmacy. Added to inter-institutional alliances such as the thriving Health Professions Student Leadership Council and the Center for Interprofessional Education currently in development between the three schools, she says, they “all point to a growing collaboration.”

“Seeing how each other work, students will gain trust and respect for their colleagues, which will translate when they’re practicing clinicians.”

Gail Rea

Drawing on each area of expertise, the planners crafted the Skyler Field scenario to require a contribution from each student representing his or her discipline. This realistic clinical experience allows the students to observe each discipline’s processes and learn how they function along parallel paths.

“Seeing how each other work, students will gain trust and respect for their colleagues, which will translate when they’re practicing clinicians,” says Gail Rea, PhD, RN, associate dean of undergraduate programs in the Goldfarb School of Nursing. “This is breaking down barriers.”

The red group’s medical and nursing students enter the room first. Led by the medical student, they question and examine Skyler, a trained actor portraying the patient, about her fall. As they exit, the occupational therapy and pharmacy students enter. They test Skyler’s range of motion and question her about her pain and home accessibility. Finally, Skyler meets with the medical and pharmacy students to hear the news: Discharge is delayed until they can do some X-rays, and her pain medications will be closely monitored in case she needs increased relief.

“We created this simulation to be intentionally different than the real world,” Glueck says. “We wanted to find out what happens if you see the patient together rather than at different times and in different settings, which can be the norm in hospitals.”

And with the rise of patient-centered care, health-care professionals’ circles are increasingly intertwined; more than ever that means that excellent verbal and nonverbal communication skills are a necessity. “An emphasis on interpersonal communication is part of the culture in the medical school,” says John Kirby, MD, associate professor of surgery and course master for surgical clerkships in the School of Medicine. “It’s important that we pass that on to our students during surgical training, too.” Kirby says the medical school is a national leader in training both future and current physicians in a culture that highlights improved interpersonal communication, conflict resolution, leadership building and patient safety. “When communication breaks down, it affects the patient,” he says.

When the simulation concludes, the students gather with their teams to reflect on their experience. “It was interesting to learn about the different priorities of the different disciplines,” one medical student offers. A nursing student adds, “We came to the same conclusions but from different angles.” Kirby polls the room: “How many of you feel this was worthwhile?” Every hand in the room shoots up.