Kristen Johnson, AB ’00, and Catherine Stites, JD ’96, both work, as they say, “on the river.” The river in question pours through the southwestern landscape more than 100 miles from their offices in Phoenix and Los Angeles, respectively, but it’s never far from their minds.

Tens of millions of people across seven states lay claim to water from the Colorado River. Everyone wants their share, including the citizens and industries in Arizona and California that Johnson and Stites represent. But, as climate change encroaches, every year there’s less to go around.

“We’re in a very delicate dance right now when it comes to the river,” says Johnson, the Colorado River programs manager at the Arizona Department of Water Resources. “The seven states are in a very difficult position of trying to negotiate how to manage the river for the next 10, 20 years.

“When you have scarcity and are trying to determine who takes what hit and how big the hits are going to be — well, nobody wants to go first.”

For now, the lower basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — are dancing somewhat in sync, offering back-and-forth proposals for how to amend existing agreements to accommodate a future with less. But with a deadline looming, there’s widespread acknowledgment of how quickly that could change. The current operating guidelines for the river expire at the end of 2026.

“In the lower basin states, we’re working together cooperatively, but these things can often blow up,” says Stites, who is principal deputy general counsel with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. “Kristen and I are currently on the same side. It’s very collegial and professional, even friendly. We all work very well together on the river,” she says, before taking a momentary pause. “Even if we may end up suing each other.”

The law of the river

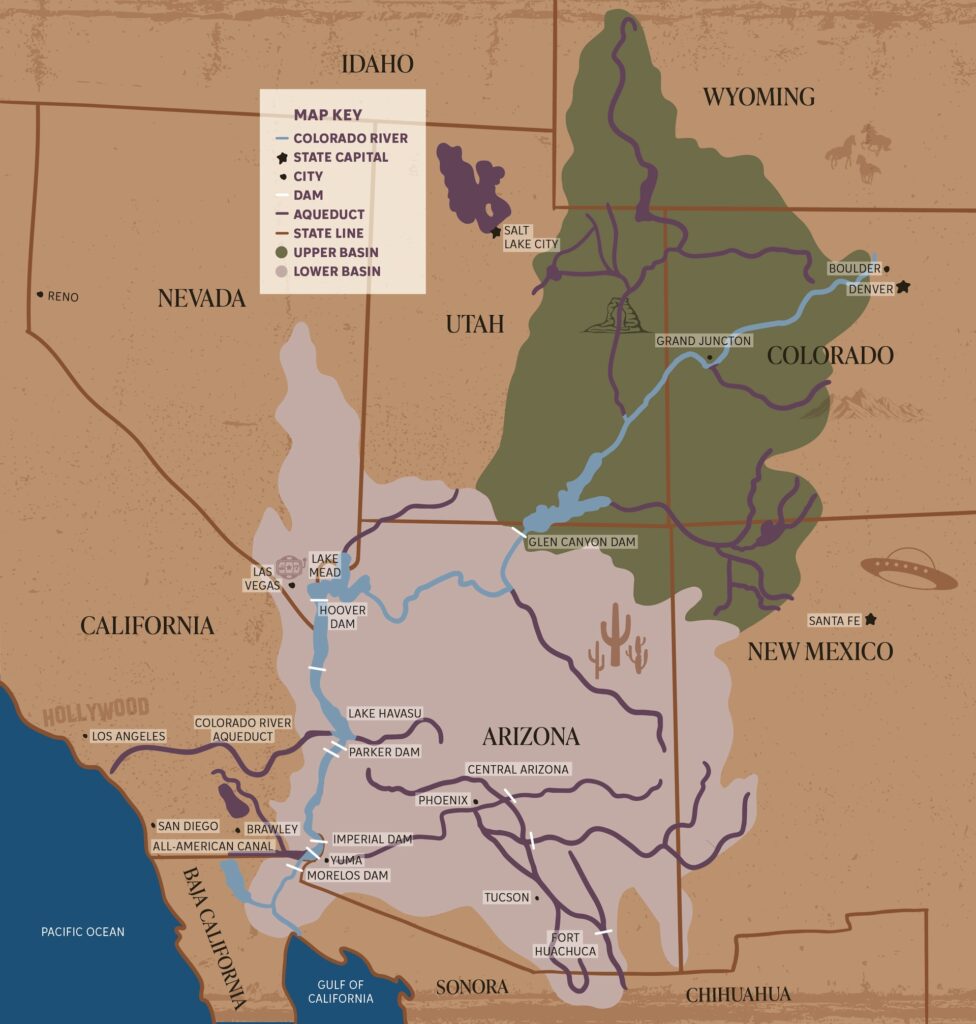

In 1922, for the first time in U.S. history, more than three states came together to divvy up a shared river resource. Per the Colorado River Compact, the upper basin — made up of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — and the lower basin would each receive 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually, with a smaller amount set aside for Mexico. (An acre-foot totals around 326,000 gallons, or the amount of water that it takes to cover an acre of land with one foot of water.)

There was a slight problem with the 1922 numbers, however, that over the course of a century-plus has added up to a major distribution headache. “We know now that the early 1920s was a particularly wet period,” Johnson says, with an average flow of around 16 to 17 million acre-feet per year. “Today, we’re looking at about a 12-million-acre-foot river. And in the future, as we’re dealing with climate change, we’re planning for an 11- or even 10-million-acre-foot river.”

That difference, as well as the explosive growth of population and water-intensive industries like agriculture, mining and hydropower, has meant the historic compact was just a starting point. Practically constant negotiations have been ongoing ever since among governments, Indigenous tribes, businesses, environmental groups and individuals vying for water rights.

Enter the Law of the River, the shorthand term for the web of laws, court decisions, agreements and treaties layered on top of the original 1922 compact. Under the Law of the River, groups have contracts with the federal government that entitle them to certain amounts of water. There’s also a priority system in place, with the highest priority assigned to farming areas like Yuma, Arizona, and Imperial, California, which together produce more than 90% of North America’s winter vegetables.

“Trying to understand how that body of law fits together to see where we are today, and how the river is managed, is a huge part of what I do every day.”

Kristen Johnson, AB ’00

“Trying to understand how that body of law fits together to see where we are today, and how the river is managed, is a huge part of what I do every day,” Johnson says, though she is not acting in a legal capacity in her current role. “Anything having to do with Colorado River entitlement, the quantity that comes to the state of Arizona and how we divide it, goes through me and my staff.” Some days that might mean talking with a farmer who wants to sell or divide his water rights; other times it’s looking over hydrologic models or considering requirements for endangered species preservation.

Across the state border in California, Stites handles the complex legal needs that come with distributing water to some 19 million urban residents. The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California includes major cities like Los Angeles and San Diego, and it’s constantly building or improving mass infrastructure to treat and move water. Stites handles environmental impact reports and compliance for the California Environmental Quality Act for these projects. In addition to her focus on Colorado River issues, she works on tribal claims for water rights.

“Without the Colorado River water supply, Southern California would not have been able to develop into what it is now,” Stites says. “If California were a country, we’d be the fourth-largest economy in the world.”

Today, around 20% of the district’s water still comes from the river. Other sources in Southern California include groundwater and water that’s been desalinated or recycled.

“One thing I’d say about water fundamentally: It’s heavy. It’s very expensive to move, treat and deliver water because it’s just so incredibly heavy. So just like with your retirement, we need to have a portfolio approach to water supply.”

The W.P. Whitsett Intake Pumping Plant is the starting point of the Colorado River Aqueduct, which delivers Colorado River water to Southern California. The intake plant pumps water out of Lake Havasu near the border of California and Arizona. (Photo: Metropolitan Water District of Southern California)

Negotiation and cooperation

From her vantage point as a longtime leader on the federal stage, Rachel Jacobson, AB ’80, understands the stakes when it comes to effective water management. “Water is becoming scarcer, and the need for water is becoming greater. That intersection creates potential security issues across the world,” Jacobson says.

Though quick to point out that she’s not a water lawyer by trade, Jacobson has held multiple governmental positions involving water management and policy. At the Department of Justice, she enforced the Clean Water Act. At the Department of the Interior, she worked on environmental conservation in the Everglades and led settlement negotiations with BP following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. At the Department of Defense, she provided legal counsel on environmental requirements and programs. Most recently, she served as assistant secretary of the U.S. Army for installations, energy and environment.

“In the Army, we were very, very cognizant of the need for water conservation,” she says. As assistant secretary, Jacobson managed physical infrastructure and natural resources for hundreds of military installations.

She points to Fort Huachuca in Arizona as a success story. Today, the base houses the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and is an important testing area for unmanned aircraft. The drought-prone area is also home to farmland and ranches. In the face of competing interests, supplying adequate water for military operations requires effective partnerships, Jacobson says.

“I think as a lawyer, the tendency is to advocate for 100%. But that isn’t conducive to success when it comes to managing water effectively.”

Rachel Jacobson, AB ’80

“Congress gives military departments funding to promote conservation practices off base when those in turn support military readiness,” she explains. That authorization allows Fort Huachuca to work with local landowners and agencies to protect groundwater. The base also has developed an extensive wastewater recycling facility. These efforts earned the base a Sentinel Landscape designation, meaning it serves as a conservation model for other military sites. Jacobson believes the outcomes there also hold lessons for the rest of the region and country.

“There must be a system of cooperation,” she says. “I think as a lawyer, the tendency is to advocate for 100%. But that isn’t conducive to success when it comes to managing water effectively. If the stakeholders aren’t working together, there will be litigation and fights. And you don’t really want a court deciding how much water should be released and where along the Colorado River, right? I don’t think policy leaders can ever take their eye off the ball here. Nobody’s going to get everything they want. There’s only so much water.”

Beyond the river

Those living outside the Colorado River Basin are not immune to the water shortages and challenges facing the region. Thor Larsen, BSBA ’98, has made his home in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in northern California, where he serves as water resources superintendent for the Nevada Irrigation District. The district covers nearly 300,000 square acres, and everyone from farmers to recreational boaters depends on snow melt and surface water to meet their needs.

“Balancing all the needs of water supply, those challenges were intriguing,” Larsen says of his decision to go into water management as a career. After a short stint in commodities trading after graduating from WashU, he moved back to his native California. Now, as superintendent of a large irrigation district, his team tracks water supply and movement through snow sampling, satellite imagery and more.

“We get a lot of variability between different water years,” Larsen says. “We can have two to three years of drought and then flooding the next year. The concern is reliability for our constituents.”

Looking at long-term climate change trends, he sees a need to build or expand reservoirs to store more water during those wetter seasons. “As warmer temperatures continue to carry on year after year, we’re seeing the snowpack diminish and rise higher in elevation. We’ll need to make up for it somewhere else,” Larsen says. “I don’t know if any new reservoirs will be completed in my lifetime, but increasing storage is a direction that needs to be sought and followed.”

While planning for projects beyond his lifetime, Larsen also faces more immediate challenges. This year, infrastructure managed by utility company Pacific Gas and Electric went offline for months, leading to water cuts. An invasive mussel species also recently appeared elsewhere in California’s waterways, requiring inspection and quarantine periods to prevent further spread.

The dizzying variety of tasks and partners makes the job compelling for Larsen, and both Stites and Johnson express the same sentiment. “It is such an intellectual challenge to try to manage the myriad stakeholders and get the messaging right,” Johnson says.

Stites has been doing water law ever since the summer after her first year at WashU Law, where she took environmental law courses and was part of the environmental law society. “It was very cutting edge at the time to have environmental law,” she says. She worked for several private law firms before joining Metropolitan in-house 20 years ago.

“When I joined, I thought what they did was fascinating,” Stites says. “We’re the largest wholesale water provider in the country, and the bulk of the people we work with are engineers. Intellectually, I love working with incredibly smart, talented people.”

Johnson, who majored in anthropology at WashU before earning a law degree at Southern Illinois University, was drawn to work in the western U.S. after a WashU fieldwork experience digging for fossils in Utah. A “suburban Chicago kid” at the time, she was entranced by the desert landscape. “If it weren’t for that field season and that experience, I would be living a very different life,” she says. A later summer legal internship at the Department of the Interior solidified her interest in water resource management.

“Ultimately, my specialization chose me,” Johnson says. “And I’m so thankful.”

Living with less

In the ongoing negotiations among the states, countless questions and scenarios are on the table: What minimum amount of water is required for human health and safety, including fire prevention? If severe drought requires diverting water from one place to another to ensure that minimum is met, who takes the cut? Under what scenarios do those with senior water rights, Yuma County included, have to cut back? And who gets paid what for all that water?

In each of these scenarios, people in the Southwest will live with less water than before. In fact, they already are.

“The current rules already have people getting cut,” Johnson says. “We’ve been in a shortage condition since 2022.” The region made headlines in early 2023 when Lake Powell dropped to its lowest-ever recorded height above sea level.

Luckily, water conservation efforts are well underway. “Per capita in the urban areas and Metropolitan’s service area, we’re using half the water we used to use,” Stites says. “Even though the population has increased dramatically since the 1990s, we’re not using more water.”

This decrease has come from low-flow toilets and appliances, the proliferation of grassless “California friendly” gardens, changes in building codes and more. Stites gives kudos to neighboring Nevada, which she says does an even better job than Southern California with water recycling and conservation — something many people overlook when strolling through flashy Las Vegas.

Across the board, there’s also increased investment in water treatment technologies to make sure every available drop is safe to consume. Metropolitan is devoting around $7 billion to construct a massive recycled-water plant in Los Angeles, part of a multistep process to make LA’s wastewater potable. This necessary dedication to water quality, as well as quantity, puts the region in conversation with efforts at WashU and around the country.

Daniel Giammar, the Walter E. Browne Professor of Environmental Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering and director of the Center for the Environment, has worked with Metropolitan to study the impacts of blending conventional water supplies with advanced treated water, examining the release of metals from household plumbing.

“We received regular shipments of this advanced treated water at our laboratory at WashU where we performed controlled laboratory experiments,” Giammar says. That research was supported by the Water Research Foundation. Last year, he was also chosen by the National Water Research Institute to serve on an independent science advisory panel that will review Metropolitan’s approach to direct potable reuse.

Through a project called Trusted Tap, supported by the National Science Foundation, Giammar’s research has the potential to help those living far outside the Colorado River Basin. With an interdisciplinary team of scientists and engineers, Trusted Tap is being developed to offer a simple approach to monitoring tap water for contaminants like lead and PFAS “forever” chemicals. In the approach, users send their existing water filters (like those made by Brita or Pur) to Trusted Tap for analysis. Importantly, Trusted Tap has the potential to help any water user, including the millions of Americans who rely on private wells.

Giammar also is one of more than a dozen McKelvey and Arts & Sciences faculty members affiliated with WashU’s Center for Water Innovation. The center facilitates partnerships and research that support sustainable water and wastewater management. Its director, Zhen (Jason) He, the Laura and William Jens Professor of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering, is an expert in the recovery of valuable resources from wastewater. The center’s regional partners include the City of St. Louis Water Division and the American Bottoms regional wastewater treatment facility.

Those working in water management see such partnerships as key to solving the ongoing issues in the West and elsewhere. Experts in policy, engineering, energy, law, the environment, communications and more are needed, as are professionals who devote their entire careers to the cause.

“I think it’s a privilege to work in this sector,” Johnson says. “We shouldn’t be undervaluing water anymore. It’s essential to everything we do.”