Lydia Paar has spent the better part of four decades in the American workforce, beginning as a 14-year-old “sandwich artist” at Subway and leading up to her current position teaching writing at the University of Arizona. In between, she worked as a Blockbuster video clerk, bartender, waitress, factory worker, hostel cleaner and the human behind a chatbot — to name a few.

In all, Paar, MFAW ’19, has held some 30 jobs across eight states, all of which has put her in a unique position to understand what it’s like to live paycheck to paycheck. The jobs also gave her insight into human behavior, from bosses who berated her to coworkers who became friends or romantic partners, to friends who became strangers. In short, her itinerant work life has given her a front-row seat to class mobility (or the lack thereof) in the United States, as well as a goldmine of material.

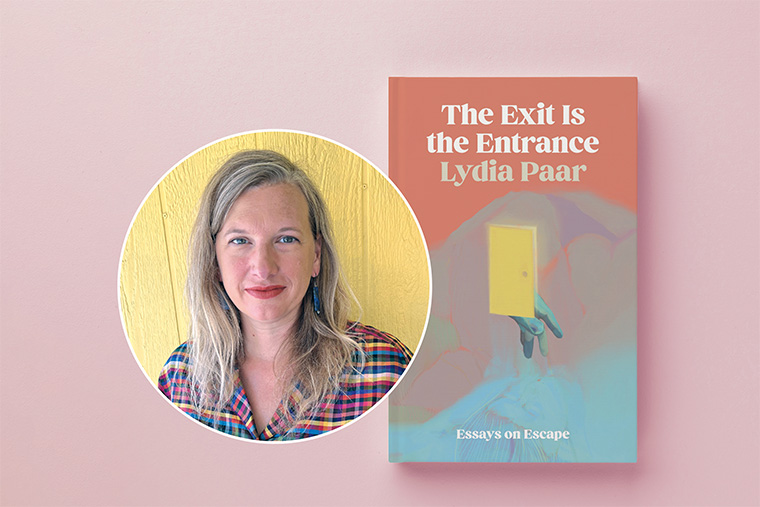

She began writing her memoir in the form of essays, some of which have been published in literary journals or collections. She deepened her storytelling skills at Prescott College and Northern Arizona University, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in writing, respectively. But it was while she was a student in WashU’s MFA Program that the idea crystallized for The Exit Is the Entrance: Essays on Escape (University of Georgia Press, September 2024), a book that traces her life from that Subway shop to teaching. Each essay could stand alone, but taken together they give the reader a road map on how to keep moving forward in the face of tremendous obstacles.

“If I’m brave enough, I write my own experience how I remember it, and put myself out there on the plate.”

Lydia Paar

One of the essays, “The Cockroach Prayer,” is about her brief time in the military, which ended with her decision to go AWOL in the middle of basic training at Fort Jackson in South Carolina. Understandable when you learn she was forced to do military drills despite complaining of pain, only to find out later — in a hospital — that she had a broken femur, two broken ribs and a fractured pelvis. “Joining the Army Reserves,” she writes, “was reminiscent of a feeling that you wanted an adventure, you called it down upon yourself, but maybe you opened the door a little too far.”

“The Cockroach Prayer” was one of the essays she submitted with her application to WashU. As an MFA student, she recalls struggling with how to structure her memoir. “I felt as if I was always writing about violence,” she says. “I figured the book was going to have less ‘me’ and more researched material about military violence, economic violence, class violence, emotional violence.”

But two WashU professors and her classmates helped define the book, through workshopping with a close-knit cohort. “It was a classmate, Gwen Niekamp, who told me, ‘You’ve had so many weird jobs. Why don’t you make this themed around work?’ I loved that inspiration.”

And she cites Kathleen Finneran, senior writer in residence, and Edward McPherson, associate professor of English, both in Arts & Sciences, for pushing the book from pedestrian reporting into art. “They demanded precision,” she says. “They’d say, ‘OK, you’re talking about this character who’s a real person and making a claim about their behavior or what you think their motivation was, but can we see that? Can we see it demonstrated?’”

She has demonstrated that and more with The Exit Is the Entrance, becoming a writer without fear. “I have a lot of things in my life that I remember,” she says. “But instead of trying to shift it into fiction — which many writers do so much better than I — if I’m brave enough, I write my own experience how I remember it, and put myself out there on the plate.”