When Elzbieta Sklodowska, PhD ’83, began her WashU teaching career in the early 1990s, she mostly taught sprawling survey courses that led students from pre-Hispanic culture up to contemporary literature. This fall, she’s guiding undergraduates through a similar range of eras and materials, but with a delicious twist. Her fall 2024 course “Not a Piece of Cake” centers on culinary encounters throughout Latin American history.

“I’ve been here forever,” Sklodowska, the Randolph Family Professor of Spanish in Arts & Sciences, says with a smile. “In recent years, we switched towards more topical approaches. For me, it’s a kind of a repackaging. Under perhaps a more attractive guise of topics — such as cities or food or love or mystery — you still get a lot of the historical overview of how literature, visual arts and film have evolved.”

Sklodowska came to appreciate the history of food through her own research. Her most recent book focused on Cuba in the 1990s, a moment of economic crisis when the Soviet Union withdrew its support from the smaller socialist country. Sklodowska devoted two book chapters to food, cooking and hunger in this so-called “Special Period.”

“It was something that I wanted to incorporate into my courses,” Sklodowska says. “I thought that this is something that students will relate to, and, at the same time, it’s a topic that is really interdisciplinary.”

Most of the 20 students in “Not a Piece of Cake” are seniors minoring in Spanish. The focus on food allows them to bring their knowledge from other subject areas like sociology, psychology, political science, economics, pre-med and anthropology into class discussions — all while honing their language skills. The course is held entirely in Spanish, and students lead many of the group activities.

Lauren Fulghum, a senior majoring in genomics and computational biology, enjoys the topical focus. “I wasn’t quite sure what to expect before beginning the class, but in the past few weeks we have been able to learn so much about the rich and complex histories of corn, cacao, and sugar (among other foods) and their influence on Latin American culture,” she says. “I recommend this course to anyone looking to learn about Latin American culture through a new and exciting perspective.”

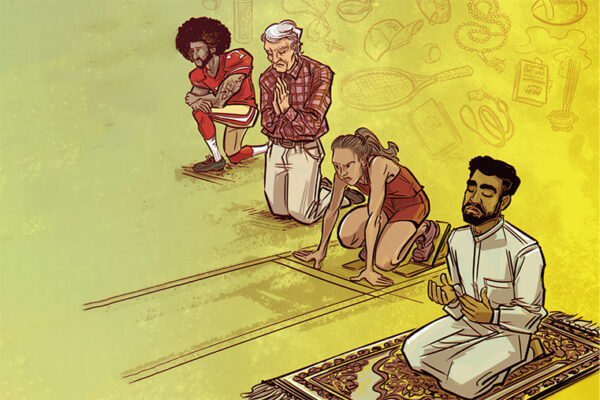

Rather than proceed chronologically, weekly topics focus on themes like “foods of violence and oppression” and “food rituals, superstitions and taboos.” While some of the themes appear lighthearted, many point to darker histories and experiences.

“The title ‘Not a Piece of Cake’ is a content warning,” Sklodowska says. “It’s not all going to be about love and chocolate and eating ice cream and feeling good. Food can be power, and it can be used and abused in many ways — from hunger, to withdrawing food, to shaming about food. The important thing for me was to see a whole range.”

Chocolate isn’t left off the table entirely, however. In the third week of the course, students were surprised to learn about the significance of the cacao bean in native Mesoamerican cultures, long before the invention of the chocolate bar in the 19th century.

“It’s not all going to be about love and chocolate and eating ice cream and feeling good. Food can be power, and it can be used and abused in many ways.”

Elzbieta Sklodowska

“Chocolate beans were used as money because they were so valued,” Sklodowska explains. “The ritual of drinking chocolate, the original form in pre-Hispanic societies, is still the practice in contemporary Guatemala or Mexico.” Alongside articles about the history of chocolate, students watched the film Como agua para chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate) and examined advertisements for chocolate products from the 20th century onwards.

Sklodowska intentionally brings in a range of source material to all her courses. Assignments in “Not a Piece of Cake” include reading poetry and short stories, viewing an online exhibition about bananas, and even watching cooking videos from a Mexican content creator on YouTube. Each source offers a new way for students to deepen both their analytical skills and their Spanish fluency, Sklodowska says.

Informed by close readings of these diverse materials, students will create their own personal food story for their final projects. Sklodowska encourages them to flex their creativity through writing, performance, multimedia creation or a range of other formats. However they choose to use and interpret their new knowledge of Latin American food, their Spanish skills will be on full display.

“It is important that this is still a language course,” Sklodowska says. “The progression in terms of their vocabulary and their self-confidence is very important — and it’s something that’s very tangible to me as instructor.

“For a lot of students, whether they’re pre-med or business, Spanish will be a tool in their professional lives. Perhaps they will forget about chocolate having been a coin in the 15th century, but I know they’ll have solid language skills combined with intercultural competence.”