It’s a rite of passage growing up: One day, you will read a book that has no pictures. Not even a line drawing. Even those who greet this milestone with excitement feel a twinge of loss.

Picture books bring the world of letters alive for us for the first time. They are the books we learn to read with. They mark the end of each day, as a beloved adult reads them to us at bedtime. Long after we’ve given them up, they still evoke nostalgia.

But what does it take to craft those cherished picture books? A lot of effort, ingenuity and imagination, it turns out.

“I think people think it’s easy until they try to write one,” says award-winning children’s author Anne Wynter, AB ’06.

Fortunately, two programs at Washington University are preparing students for the field. The Communication Design program at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts teaches students about the world of commercial art by having them learn design and illustration.

“Design and illustration are really interconnected,” says John Hendrix, the Kenneth E. Hudson Professor of Art at the Sam Fox School and a New York Times–bestselling children’s book author himself (The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler; Miracle Man: The Story of Jesus; and Drawing Is Magic, to name a few). “Illustration is the relationship between text and image; illustration does not exist separate from the act of reading. In the world of children’s books, it is also a design problem. It is the illustrator who decides where text and images fit on each spread.

“At the Sam Fox School, we treat an illustrator not as someone just waiting for the phone to ring to get an assignment, but as an author and the person who can also write the ideas and the stories they will then illustrate,” says Hendrix, who is also founding chair of the MFA in Illustration & Visual Culture program.

Over in Arts & Sciences, the Children’s Studies minor is helping students learn “what has been done in literature for children,” says Amy Pawl, the program’s director and a teaching professor in English. One thing students learn is to see how young readers of color have long been ignored in children’s literature.

“The minor helps students feel the imperative to create really good, representative, inclusive, powerful literature for all children now,” Pawl says.

The results are children’s books that have won awards, inspired birthday parties, paid tribute to trailblazing historical figures and increased representation. And they have been the stars of many, many bedtimes.

Magic in a book

Adam Rubin, BFA ’05, is something of a play expert. He’s a partner at Art of Play, where he makes real-life optical illusions. One such illusion pairs two dishes that seem to grow and shrink when laid next to each other.

He has also crafted magic tricks for the likes of David Blaine and Derek DelGaudio. He founded the long-form improv group Suspicious of Whistlers at WashU, and during the pandemic, he created Bizarre Brooklyn, a “magical mystery and history tour” of the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood.

“Some people lose their connection with the childlike sense of wonder they had when they were young,” Rubin says. “I try very hard to hang onto that.”

It definitely shows up in his writing as the author of children’s books including the juggernaut Dragons Love Tacos and its sequels. Dragons Love Tacos has sold more than 5 million copies and inspired legions of devoted fans (as well as a few birthday parties).

“It’s very exciting for kids when things go haywire if there’s no actual danger,” Rubin says. In the book, dragons accidentally burn a house down.

At WashU, Rubin wasn’t sure what he would study. He had always loved writing, but he was also interested in art. His willingness to take classes in both led him to work in advertising and then later to create, with illustrator Daniel Salmieri, his first picture books.

Another WashU alum, Corey Mintz, BFA ’05, introduced the duo, and their first effort was Those Darn Squirrels, about a man battling squirrels at his birdfeeder. It was based on Rubin’s dad.

“It was fun to watch a grown man engage in a battle of wits with a bunch of rodents and lose,” Rubin says. “Now that I’m grown, I’m having the same problem.”

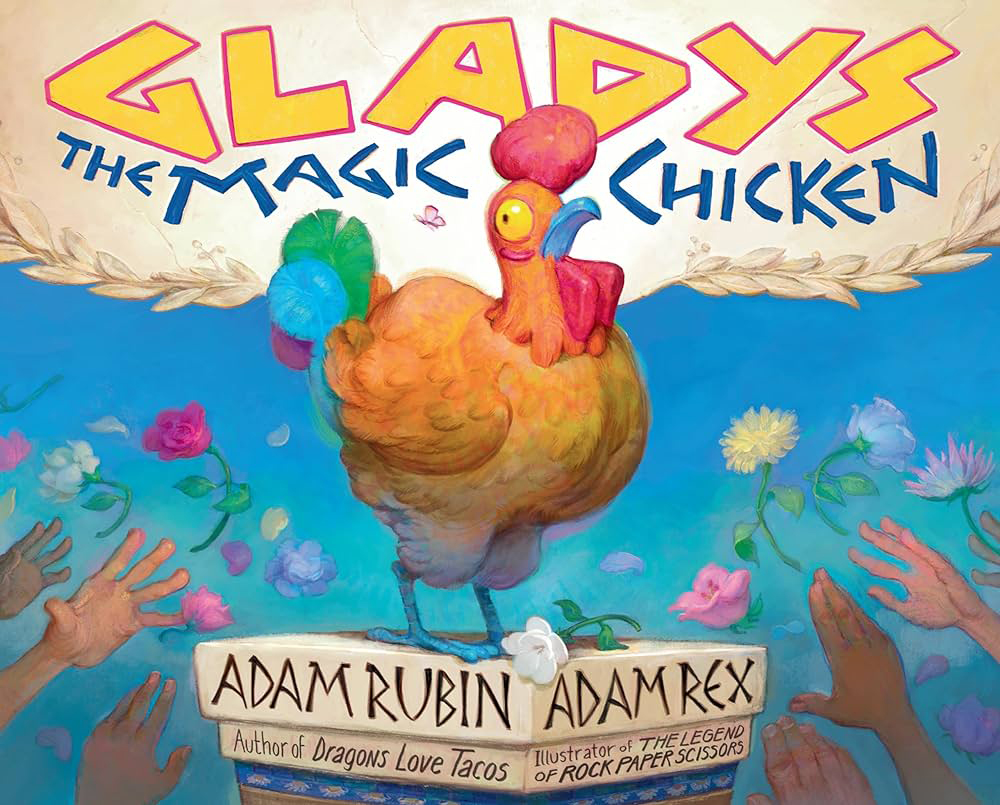

Rubin and Salmieri later got agents and created a bunch of other books including Robo-Sauce, which turns into a robot at the end. Rubin has also worked with other artists, such as Adam Rex, who illustrated Gladys the Magic Chicken.

After years of creating picture books, Rubin recently pivoted to middle school readers with his books The Ice Cream Machine and The Human Kaboom. Each book contains six stories with the same title. Both became New York Times bestsellers. And in each one, he encouraged young readers to mail him stories that riffed on the book titles.

The result: Rubin received hundreds of stories for each book and selected six to appear in the paperback versions. The idea was to encourage kids to be not just readers, but writers, too.

“It’s so important to encourage creativity in kids,” Rubin says. “A kind word from an authority figure goes a long way. That was something that inspired me as a young writer and what I’m trying to do for as many kids as possible now.”

Planting the seed

To make Rubin’s point, Anne Wynter, AB ’06, studied drama at WashU, but she took a course on writing for children and remembers getting an encouraging note from the professor on her portfolio. “He wrote that I should keep writing, and that I have what it takes to be a professional writer one day,” Wynter says. “That was really, really encouraging.”

The professor, Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in Arts & Sciences, planted a seed that by 2017 had grown into a full-blown picture book.

“What made me decide to work on picture books specifically was when I had my children and we were reading a ton of picture books,” Wynter says. She wrote Everybody in the Red Brick Building about a baby in an apartment building who cries and starts a chain reaction, waking up one neighbor whose noise then wakes up another.

“I was definitely inspired by the fact that we lived in an apartment, and my second child had a really loud cry,” Wynter says. The book landed Wynter an agent and an Ezra Jack Keats (EJK) Award Honors in 2022. Each year, the EJK Foundation recognizes early career illustrators and writers who create “books that reflect our diverse population, the universal experience of childhood and the strength of family and community.”

“It was amazing seeing people’s reactions, and it’s a really fun book to read aloud,” Wynter says.

Wynter also has written a series of board books about a mischievous toddler. “One of the most fun times I have writing is when I’m writing board books,” she says. “I enjoy creating a rhyming scheme and a story that will appeal to all ages.”

Her second picture book, however, was not as fun. “It was my hardest book to write,” Wynter says. “It went through a lot of iterations and a ton of drafts. But early one morning, a pattern of the words just hit in the right way. And I was like, ‘This is it. I’ve finally found it.’”

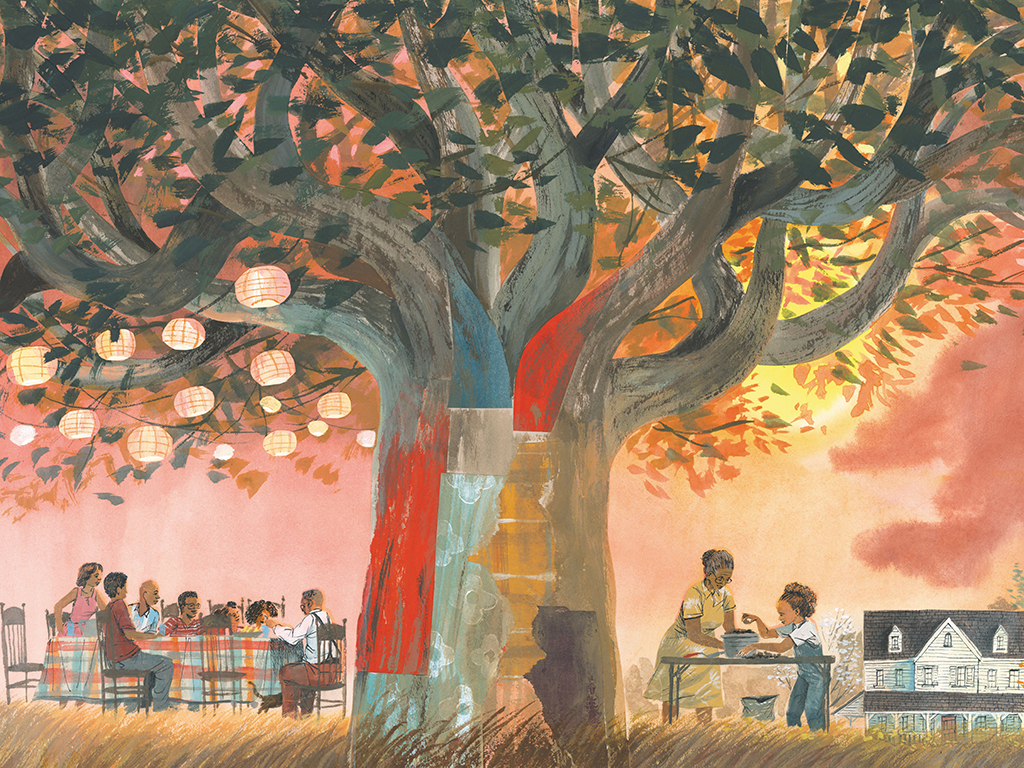

The result is Nell Plants a Tree, a book about a young girl who plants a pecan tree that she then gets to watch her grandchildren play under and climb.The book, which recently earned Wynter an Ezra Jack Keats Award for writing, features an African American family, as do Wynter’s toddler books.

“I wanted to write children’s books because I wanted to see characters who look like me and my friends and family,” Wynter says. “When I was young, and I was reading a ton of books, I felt like I almost never saw books with protagonists who were Black. So, I wanted to write books that were more representative. It’s really important to me, maybe the most important thing.”

Adding to the tapestry

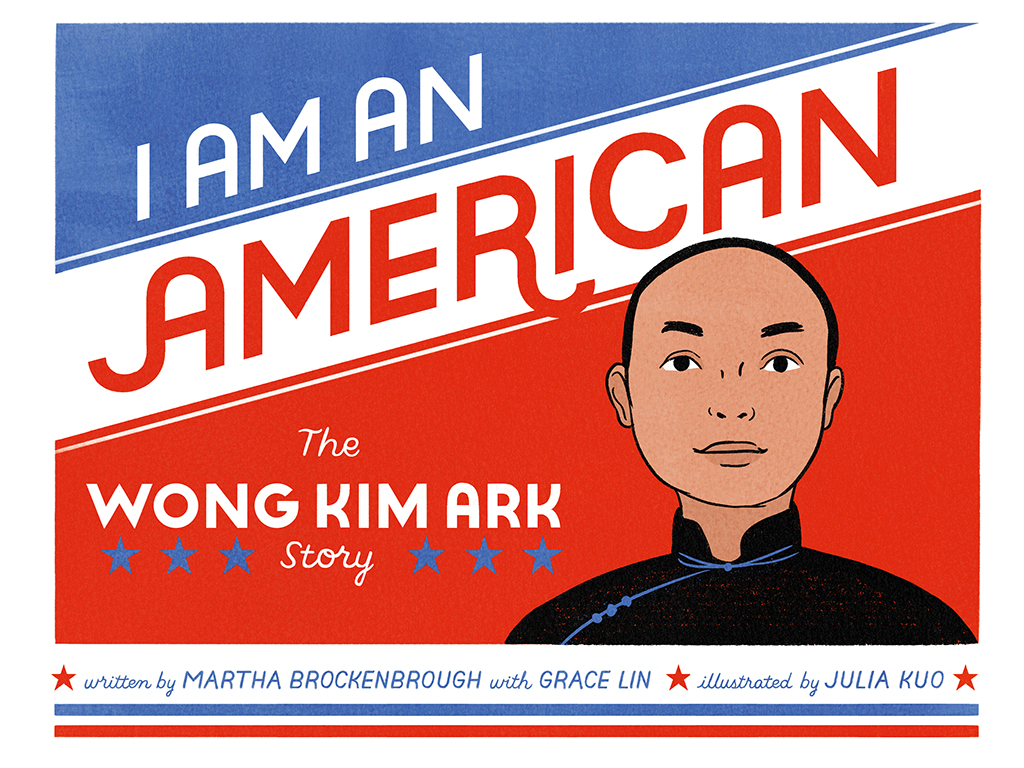

The first book that Julia Kuo, BFA ’07, illustrated was Clara Lee and the Apple Pie Dream by Jenny Han. You know, the Jenny Han of To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and The Summer I Turned Pretty fame, both now Netflix series.

Kuo, who found her agent through that project, was brought on by Little Brown editor Alvina Ling, who is known for pioneering Asian American authors, illustrators and other creatives.

As a Taiwanese American, Kuo has a similar aim for her own work, which includes illustrations for I Dream of Popo, about a young Taiwanese girl who moves away from her maternal grandmother (Popo) in Taiwan, and I Am an American: The Wong Kim Ark Story, about a Chinese American man’s fight to have his U.S. citizenship recognized.

“While I’m working toward representation in a basic sense — simply portraying Taiwanese Americans and Asian Americans existing — my goal is specificity: We are not a monolith, and so every additional story that shows nuance and diversity makes a difference,” Kuo says.

Kuo came to WashU because she wasn’t sure if she wanted to major in business or art. Able to study both, she started leaning toward art. The Communication Design program teed her up for a career in art, and through Linda Solovic, a Sam Fox School senior lecturer who owns her own studio, Kuo landed a job at American Greetings right after graduation.

In 2010, Kuo found freelance work with such outlets as The New York Times while continuing to create public art, run a paper goods shop and do illustration.

“I was pretty open to whatever opportunities came my way,” Kuo says of her career.

She recently published two show-stopping picture books that she also wrote: Let’s Do Everything and Nothing and Luminous: Living Things That Light Up the Night.

Let’s Do Everything and Nothing is about a girl and her mom doing, well, everything and nothing together. “It juxtaposes the beauty of going on these fabulous adventures with the experience of being still and being at peace and at rest at home together,” Kuo says.

Both books have Asian protagonists, and Kuo often hears from fans that they’re excited to see themselves in a book. “It’s a novel thing for many readers,” she says. “So every additional story told by a person of color adds to the richness of who we are — not only for ourselves, but also for others to see and to know us a little bit better.”

Drawing history

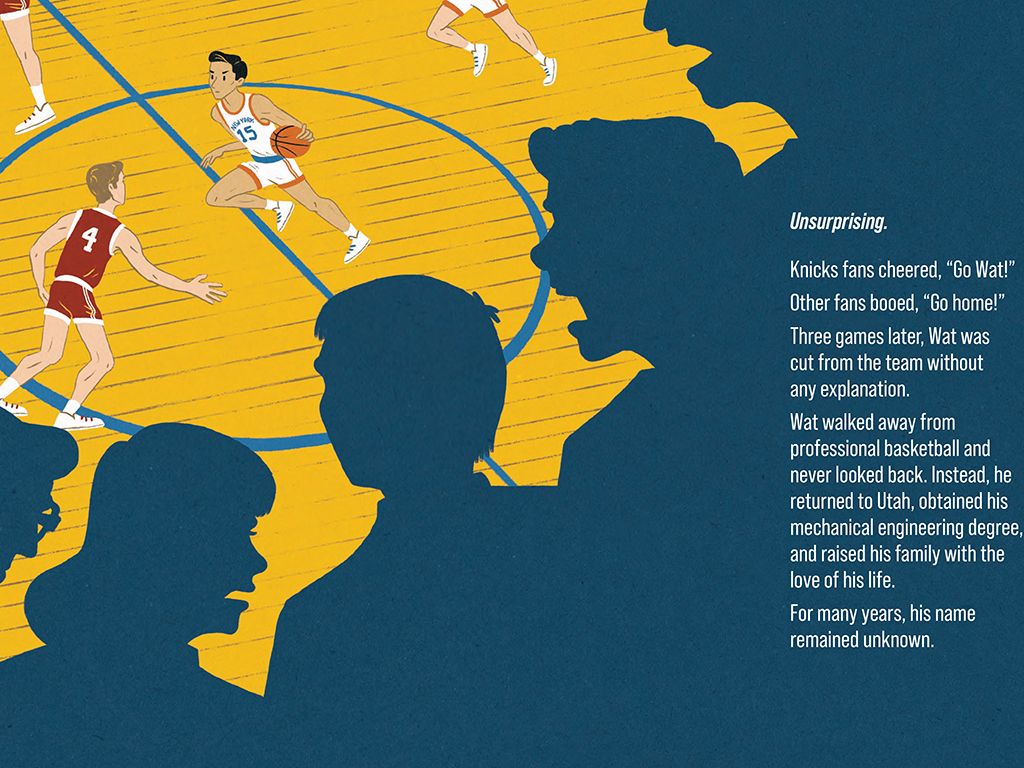

When Naomi Giddings, BFA ’16, received her first children’s picture book commission, she wasn’t familiar with her subject, Wataru “Wat” Misaka, a Japanese American who broke the NBA’s color barrier. But she knew someone who was.

“My grandfather actually remembers back in the 1940s reading about Wat in the Japanese American newspapers of the time,” Giddings says. Misaka played for the New York Knicks during the 1947-48 season. Anti-Japanese sentiment was so high, though, that the team let him go after just three games.

This was a post-Pearl Harbor America, where Japanese people were interned in camps for years if they lived on the West Coast, losing all of their personal possessions in the process.

“My grandparents were actually incarcerated during that time,” Giddings says. The experience was so harrowing that their families (her grandparents were kids at the time) didn’t return to California, but instead moved to Chicago. So illustrating Rising Above: The Wataru “Wat” Misaka Story by Hayley Diep was “deeply personal.”

The project was personal for Misaka’s kids, too, who enhanced Giddings’ illustrations by sharing personal details about their dad. “They said, ‘He was really good friends with this one athlete, so if you could feature him on this page, that would be great,’” Giddings recalls.

Giddings had only four months to do the illustrations (a normal timeline is six), but she says she was up for the challenge after her time in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

“The Communication Design program was really wonderful for me because it was so geared toward becoming a professional by working with clients while also getting to do creative things,” Giddings says. “There was a point where I got to do a mock-up of a spread for a picture book. That work influenced the picture book that I just did.”

Telling the story of a forgotten trailblazer of color also resonated with Giddings. At WashU, her thesis project involved adding diversity to children’s books — mostly chapter books, such as Matilda or Esperanza Rising. Sometimes she’d just depict the characters of color in the book, but when a book didn’t have any, she would “reimagine other characters” to “add diversity to the literary canon.”

The Misaka story didn’t require a reimagining. “The idea of adding to our history of people of color in sports and more largely just people of color being trailblazers and barrier-breakers was really exciting,” Gidding says. “I felt honored to be chosen for the project.”

A family story

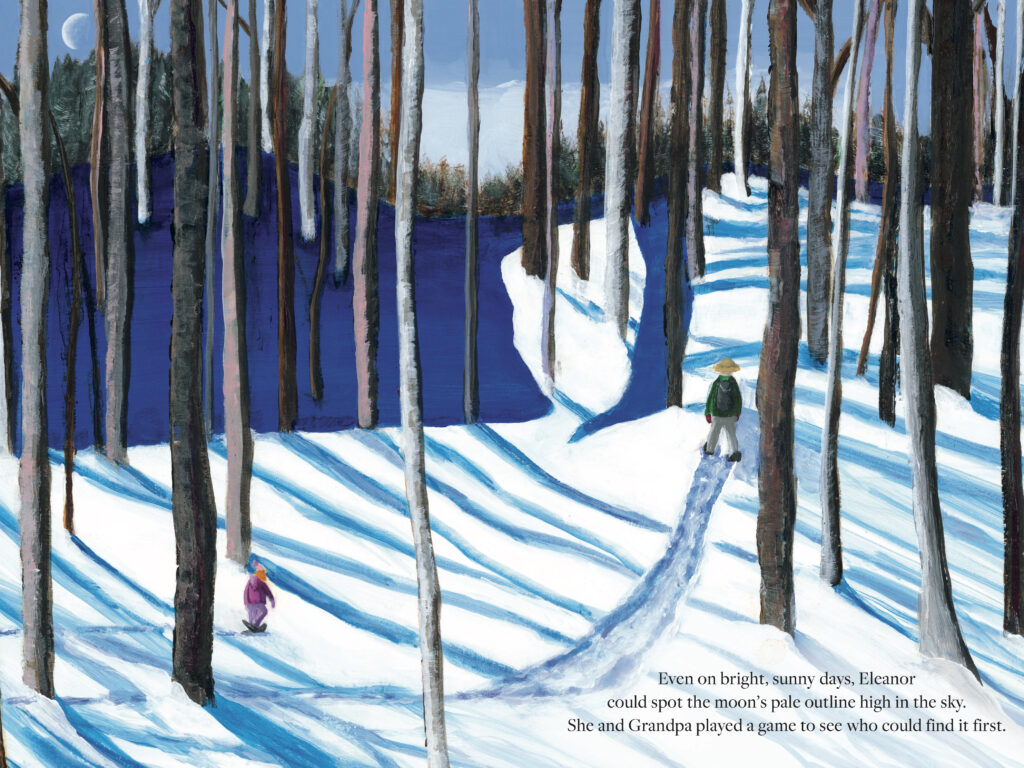

Twenty years ago, Maggie Knaus, MFA ’95, wrote a children’s story about her first child, Eleanor.

“My daughter and my father were really close,” Knaus recalls. And when Eleanor was still young, she and her family moved from Washington, D.C., where Knaus’ father lived, to Canada. But he’d given young Eleanor something to remember him by: the moon. Their shared love of the moon was the touching connection that inspired Knaus to write a story.

“When we moved, a lot of things in the world reminded Eleanor of the moon and of my father,” Knaus says.

Her father and daughter both loved the story, but Knaus never had any plans to make it into a book, much less publish it. She was a photographer by trade. In Washington, D.C., she’d operated an art studio that was open to the public. Through people strolling in off the street, Knaus had met her husband and gotten a job at the White House Historical Association.

She focused on photographing White House staff, such as the woman who was in charge of the White House mail and the gardener who took care of the Bushes’ dogs. “It was so much fun,” Knaus says.

After the family’s move to Canada, an accident made Knaus reconsider the story she’d written.

“I had a 110-pound dog, and I used to take him for walks and throw a Frisbee for him. One day, I went to reach for the Frisbee, and he came charging into me to get it and, unfortunately, gave me a concussion,” she says. For months after, she couldn’t read or look at screens.

“The only thing I could do was paint,” Knaus recalls. “So, I started painting. And when the concussion got better, I joined a board at the Toronto Public Library. A lecture by a visiting author made me think, ‘That’s what I can do with my painting now. I can illustrate that old story.’”

Knaus shared her story with another author, who said it had to be published. “She got me in touch with her agent, and it took off from there,” Knaus says. The result was Eleanor’s Moon, about a young girl who has a special connection with the moon and her grandpa.

Knaus says that she “did everything backward” with her children’s book. Typically an editor will greenlight a story and then find an illustrator. But Knaus’ agent wanted to sell the illustrations and book as a package, and it worked.

But the book also left Knaus with a small debt to pay. “I’m working on a new book now for my second daughter, Jane,” she says with a smile.

From cards to books

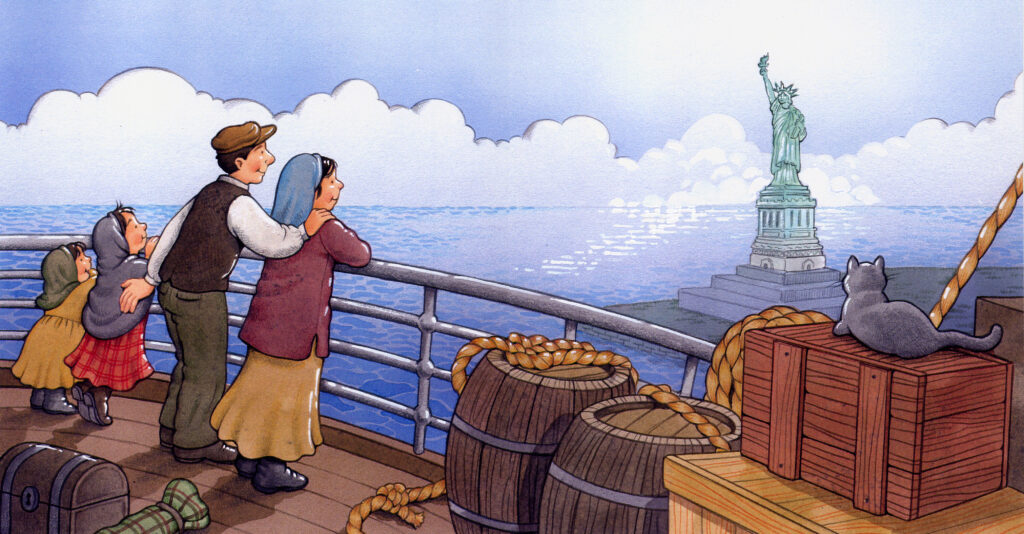

After graduating from Washington University, Dana Gustafson Regan, BFA ’83, landed at the Midwest’s mecca for artists: Hallmark.

At the time, “There were 800 artists working there,” Regan recalls. “That was bigger than my hometown.”

Working at Hallmark, where Regan designed stuff for kids like Advent calendars and birthday cards, was like a master’s program in being an artist. But after five years, she was ready to fulfill her lifelong dream of being a children’s book illustrator.

“In second grade, I wrote an essay titled ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ And in it, I said I was going to write and illustrate children’s books,” she says.

So Regan traveled to New York from Kansas City to show publishers her portfolio. But she soon realized she was never going to book enough jobs to make it as a freelancer that way. So Regan found an agent.

“On my fourth trip, I finally decided to make all my appointments with agents instead of publishers,” she says.

And that decision paid off. Today, after 30+ years’ experience, Regan has published 70+ books and illustrated titles such as the Messy Bessey series and the ASPCA Kids Pet Rescue Club series. And her Night Before Christmas board book has been her longest-selling book, in print since 1992.

One of Regan’s favorite jobs over the years has been creating the hidden pictures for Highlights Magazine, where an image that looks perfectly normal has a dozen or so hidden items in it. “I love doing hidden pictures,” she says, “but it’s hard.”

Early in her career, Regan wrote her first book: Monkey See, Monkey Do. She also illustrated it with rosy-cheeked monkeys. The story rhymes, a feature that Regan likes in books for early readers.

“My dad was the high school band director,” she says. “So I was writing in four-four time. It helps kids get the words because kids can hear rhymes even before they can read them.”

Regan tapped into that rhyming scheme again for her latest early reader series, Mike Delivers. It’s about a delivery hedgehog that lives in a friendly small town.

“I was thinking about my small town in northern Wisconsin,” Regan says, “how everybody knows everybody, and everybody helps everybody.”

Unlike Monkey See, Monkey Do, Regan didn’t illustrate the Mike Delivers series. Instead, the publisher suggested an artist from Spain. “I loved it because she brought a whole different sensibility to it,” Regan says. “I’m picturing Wisconsin, and she’s got sidewalk cafés and fountains and scooters. I thought, ‘You’re leveling this up.’”

For more titles for young readers by alumni