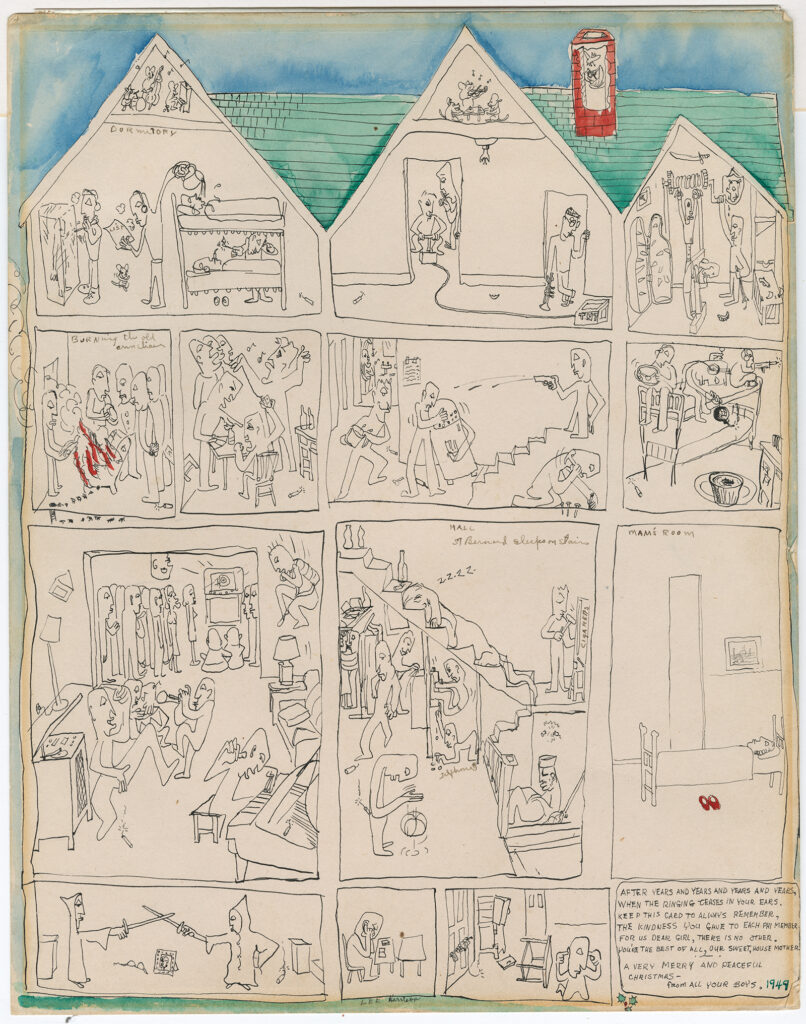

The hand-drawn card from 1949 interrupted, like a surprise party, what was an otherwise mundane day. A page-turn away from being tossed in the trash, it was placemat-sized and tucked within an old parcel map book as big as a cookie pan. The illustration featured a dollhouse-style cross section of a vibrant fraternity house.

I examined it. Each room of the precisely rendered four-level residence was teeming with people and action. Whoever drew it had fit entire stories into panels that captured the thrills of post-WWII college life in America: books, music, sex, cigarettes, TV, antics, senseless fun. A kind of idea explosion on paperboard.

Implied noise and motion were everywhere. A jazz trio was rocking on the main floor as a guy bounced on the couch; a St. Bernard was snoring on stairs, above a couple kissing in a cubby. Elsewhere, a dozen-odd awestruck students were huddled around a new mass-market device called the television.

Each of the 17 panels was its own mini-drama. Sword fights. A mock medieval dungeon (in the attic). A mouse string quartet. In the basement, beneath it all, one solitary student sat at a desk with a few open books, his fingers in his ears to drown out the noise. The panel was captioned “Lee Harrison.”

Holding it in the sunlight, I decided it must be a print. It was too well-crafted. But the watercolor blue skies and red brick chimney were hand-painted. The razor-thin lines capturing coeds were in real ink. Each joyous stroke was etched with intent.

Amid the clamor, one area was silent.

Near the bottom in a panel captioned “Mam’s room,” a woman was asleep in a bed. She’d neatly placed her red slippers underneath the bed and seemed blissfully unaware of the chaos surrounding her.

Beneath slumbering Mam was a handwritten poem:

After years and years and years and years,

A very merry and peaceful Christmas —

When the ringing ceases in your ears.

Keep this card to always remember,

The kindness you gave to each Phi member

For us dear girl, there is no other.

You’re the best of all, our sweet, house mother.

From all your boys, 1949

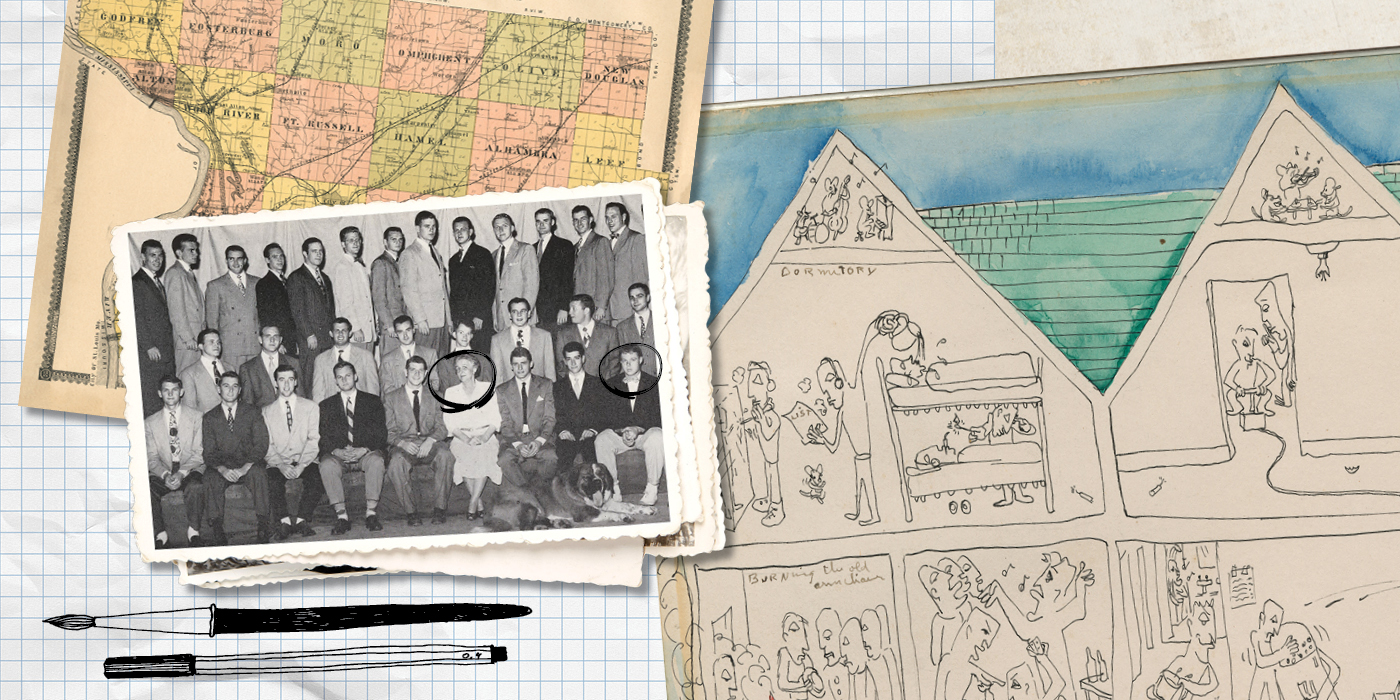

Mam was my great-grandmother, Juanita Berenice (Barco) Baird. I knew her as Grandmommy. And Lee Harrison, from just across the Mississippi in Belleville? Online sleuthing eventually led me to the artist, who had signed the card to “Mother Baird” on the back. A decade after drawing this for her, graduating with an art degree and returning a few years later for an engineering degree, Harrison, BFA ’52, BSME ’59, successfully embarked on a mission to revolutionize computer graphics.

You’ve seen the Emmy-winning innovator’s work. In the original version of Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory during the Oompa Loompa song, when the lyrics “What do you get when you guzzle down sweets?” zigzag across the screen to the sound of the music, Harrison’s invention, Scanimate, is animating the query. Once you know what it is, you’ll start seeing Scanimate action all over 1970s-era TV series, local news stories and highlight reels. The shimmering early-era HBO logo? Yep.

“Before we came on the scene, graphics, especially, were static,” Harrison told Washington Magazine in 1997. “We started animating openings for shows and were the first to use electronic animation to create distinctive logo packages for television stations.”

I was unaware of this at the time. But I certainly expected — or hoped — that after graduation this Harrison guy used the skills so evident in this astonishing card. I also wondered whether Mother Baird’s kindness had rubbed off on him and how she kept all her boys in line. I started poking around.

The ‘right kind’ of housemother

Keeping the students out of trouble was among the roles of housemothers (now called live-in housing directors) in the 1940s. Well, that and virtually everything else that mid-century patriarchy deemed mom jobs: cooking, cleaning and household stability included.

Comments on the job description sound laughably condescending today: “The housemother can be a real tower of strength in the purchase of provisions, in the planning of meals and in the regulating of dining room service,” one participant at the National Interfraternity Conference said in a 1946 speech called “Fraternities on the Postwar Campus.” It was the same year that Mother Baird, two years a widow, joined on at Phi Delta Theta fraternity as a housemother.

The speech described housemothers’ prerequisites as being “worthy of the name and who shall … add a motherly touch to an otherwise all-male establishment.”

Requiring full-time fraternity housemothers was hardly a foregone conclusion at the time, especially among privileged men. “There is so much emphasis on the feminine side, with feminine instructors and outside diversions, that we are getting away from something of the masculinity of the older eastern colleges,” one wary fraternity official observed at a late 1930s conference. If Nazi-killing soldiers didn’t need troop mothers on the front lines, why should young Midwestern men need them for studying?

Washington University Dean G.W. Stephens disagreed. At the annual get-together of the National Association of Deans and Advisers of Men in 1944, he proclaimed that “the housemother is most strongly to be desired,” submitting that “a boy who comes to the University has left a home in which there was a mother, and … the fraternity house should be the nearest equivalent to a home in the literal sense.” The dean felt inclined to include a caveat: “assuming that she is the right kind.”

Whether Mother Baird was “the right kind” is an open question. When her first husband, Homer Baird, died in 1944 of what she described in her diary as “a heart ailment,” she was a mother of two grown, married daughters, Anna Maria (my grandmother, whom everyone called Marie) and Judy (my great-aunt who insisted that her well-to-do husband drive her everywhere in a Cadillac limousine). Within two years of leaving the “housemotherhood,” Mother Baird had married a man in El Paso, Texas, only to divorce him six months later. Marie was often embarrassed by her mother’s outgoing nature — at least according to the first of her three children: my mom, Sue.

An idea hatched

Lee Harrison III didn’t know Mother Baird from Mother Superior when he arrived at Washington University in 1949. He’d grown up across the Mississippi River, born into a successful family of engineers in blue-collar Belleville, Illinois. His grandfather was the inventor of a P.T. Barnum-inspired machine known as the Jumbo steam engine. Majoring in art, playing football and becoming a member of Phi Delta Theta, the younger Harrison embraced his years at the university.

He picked a good time to be at the School of Fine Arts. A year earlier, the great German expressionist painter Max Beckmann had arrived to teach after being exiled and having his life upended by the Nazi regime. Records don’t indicate whether Harrison had Beckmann as an instructor, but the student’s assured hand on the Christmas card certainly suggests a precocious talent worthy of notice.

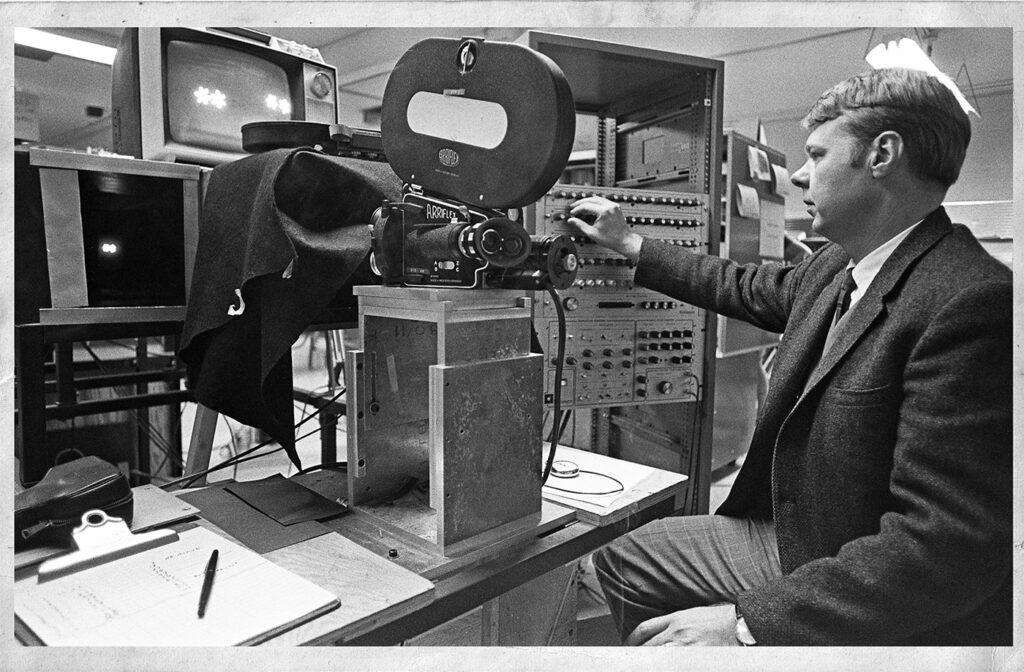

After his 1952 graduation and a two-year stint in the Coast Guard, Harrison traveled to Central America, he told Washington Magazine in 1997. While there, he conceived of what he called “a magic box” for graphic animation. Returning to the St. Louis area, he re-enrolled at Washington University to pursue an engineering degree.

This drive for a cross-disciplinary education at the university predated by decades innovative programs such as Arts & Sciences’ new Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures. “At first I wasn’t even sure that what I wanted to do could be done,” Harrison said of his idea. So he pursued knowledge that would build on his art degree and enable his invention. Harrison ended up with more than a dozen patents to his name.

“What he was doing was very experimental at the time. It was also very novel, the idea that he was able to take this idea and go mainstream. When he was starting, the notion of using computers to make imaging was still considered bizarre.”

— Tom Sito, author of Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation and professor of cinematic arts at the University of Southern California

Evidence of a rich life

By the time she arrived as a housemother in 1946, Mother Baird was a three-time grandmother. Born in 1888, she married Homer when she was 20. He was an Edwardsville dentist whose family lived in the bedroom community’s tony St. Louis Street district.

Though hardly a daily journaler, Mother Baird was dedicated to the idea of keeping detailed notes on her travels and experiences, even if in practice entire swaths of her dated diaries and calendars are blank. But she was uninhibited in what she kept and actively compiled evidence of a rich life within her belongings, tagged each piece with descriptions and scribbled asides as if someday they might help tell a story.

Mother Baird, too, seemed a little bizarre, at least judging by a few of the three dozen photos of her rescued from the same leather chest that housed the book holding the Harrison illustration. In one black-and-white image at an outdoor party in 1933, she’s standing like a stork doing the cancan, her front leg kicked high and left arm hooked over her head. She’s wearing a dress, and you can clearly see her underwear.

The “right kind” of woman might have burned this photo long ago. But she kept it in her photo box, not far from images of her sitting on a camel in front of an Egyptian pyramid and another of her posing in Florida with five parrots perched on her arms and head. A shot of her leading a group through a street in Italy is captioned, “I am telling Gertrude Duetmar how the Romans did it.” One photo, dated 1950, captures her posing at Washington University with two young men and a St. Bernard she identifies as “Scrubbie.” That same dog is snoozing on the stairs in Harrison’s drawing.

After Mother Baird died in 1974, my grandmother added further documentation when she could before piling everything into a dingy leather trunk. It sat in my grandparents’ basement until both passed in the 1990s after more than 60 years of marriage.

The physical evidence of Mother Baird’s life wasn’t much to look at: piles of photos, paperwork, ragged books, the lace collar from her 1908 Stix, Baer & Fuller wedding dress — the kind of stuff that you can’t just delete with a keystroke, especially when blood’s involved. The recent owner of a 10,000-square-foot four-family in St. Louis’ Benton Park, I unloaded the trunk and its belongings, including the Madison County Property Ledger, into my basement.

An idea takes flight

Harrison earned his engineering degree in 1959, moved to Denver and founded Lee Harrison Associates, which evolved into Control Image Corporation before becoming Computer Image Corp. in 1969.

Within a few years, his trio of machines, Scanimate, ANIMAC and CAESAR, were thriving in the graphic animation industry, offering jaw-dropping new possibilities for creatives, advertisers and filmmakers. The most successful of them, Scanimate, was much cheaper than traditional cell animation. Broadcasting Magazine reported in 1970 that old-school animation required more than 5,000 painstaking drawings and months of man-hours for similar results.

“Because the Scanimates produced output in ‘real-time,’ the clients could literally sit down and say things like, ‘Make it move a little faster,’ or ‘Can you make it more of a teal color?’” Dave Seig, a former Computer Image employee and an expert on Harrison and Scanimate, wrote in an essay on his website. “The animators would tweak it, get an approval, tape it, and the guy would walk out with his master.”

“Everybody was looking for a new look, a different way of looking at visuals,” says Moving Innovation author Sito, adding that media companies wanted “the Peter Max–style, very pop-art look that Scanimate produced.”

As Scanimate’s popularity soared in America, its influence began to spread globally. Artists like Ringo Starr and Todd Rundgren saw the potential for it to become a game-changing “visual equivalent of a Moog synthesizer.” TV producers eagerly embraced Scanimate for intros and effects in shows like The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, The Electric Company and The Pink Panther cartoon.

Michael Webster, a president of Computer Image in the 1970s, noted in a trade magazine interview that the system’s accessibility made it a creative tool for anyone with imaginative ideas: “The operator can produce an infinite variety of spectacular effects and put an image through an incredible range of movements by simply manipulating knobs and dials,” Webster said, adding that, with the technology, “graphic effects can be done that were never possible with conventional animation.”

It was as if Harrison had jolted to life the kinetic energy expressed in his holiday card to Mother Baird.

Curating a life

I don’t know whether my great-grandmother kept up with her former charge’s success in computer graphics. She was 84 and blind by the time Harrison got his Emmy in 1972, the first-ever awarded in the Outstanding Achievement in Engineering Development category. I was 6.

When she was living in a duplex next door to my grandparents in Edwardsville, I remember her as a joyous presence, quick to laugh. She seemed not just “the right kind,” but perfect. Her belongings bore that out. She was a brilliant curator of her own life.

She could often be found reading books written in Braille or listening to the radio. She’d quit being a housemother in 1950 and quickly took to traveling. Her six-month Texas marriage occurred in 1952, but other than a quick datebook mention, it barely registered. According to my mom, Mother Baird never discussed it.

Harrison sold his company in 1987 and eased into a Colorado retirement with his wife, Marilou. He passed away in 1998. Though he hadn’t painted since traveling to Central America in the 1950s, he picked it up again in his later years.

He did so, he recalled to Washington Magazine, for the same reasons he composed that card to Mam:

“To give myself an out from the partying that was going on around me. It was a way to record the places where I was staying, and some of the fun we had.”

— Lee Harrison

He succeeded.