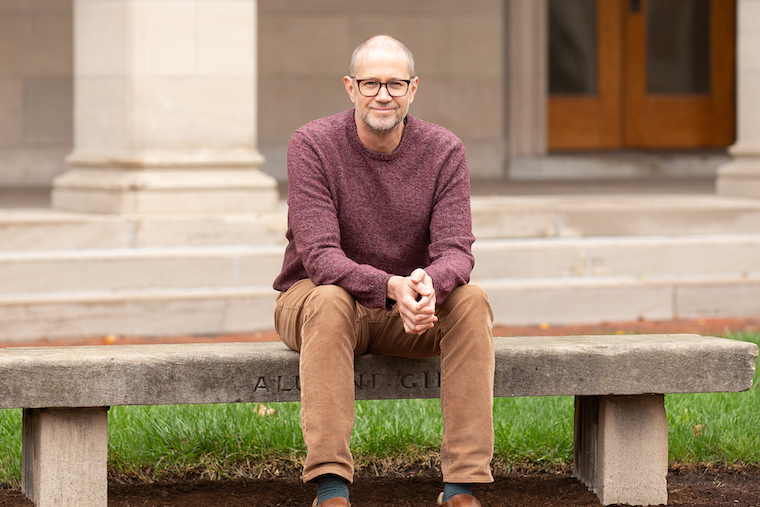

“The key was the voice,” says Martin Riker. “I’ve had the idea of writing a book that takes place over the course of a single night for probably 15 years. But until Abby’s voice came into my life, this book wasn’t possible.”

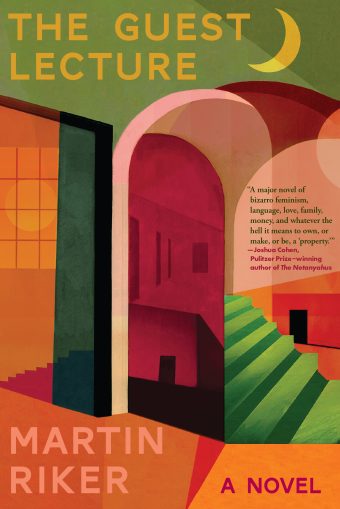

Riker, who directs the new publishing concentration in the Department of English in Arts & Sciences, is discussing his second novel, The Guest Lecture. Released by Grove Atlantic, the book is among the best-reviewed of the year, with glowing notices in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New York Review of Books and many others.

The story centers on Abby, a young scholar preparing, if not sufficiently prepared, to deliver a talk on economist John Maynard Keynes. In her hotel room, lying still beside her sleeping daughter and husband, Abby organizes her thoughts while wandering the memory palace of her mind.

The “memory palace,” sometimes known as the “method of loci,” is an ancient system of memorization that pairs information with specific imagined spaces. The device can lend Abby’s ruminations a stream-of-consciousness urgency. And yet, says Riker, “this is a highly plotted book. Before I started writing, I had a schematic of all the different rooms and all the topics and anecdotes that would come up in each.”

Accompanying Abby is the daunting figure of Keynes himself. With his dry humor and push-broom mustache, Keynes is at once guide and destination — the Virgil and Beatrice to Abby’s tenure-less Dante. He’s also critic and review committee, offering advice and chiding Abby’s procrastinations.

“Abby’s not good at public presentation,” Riker says. “But she is courageous, and she has a strong sense of the imagination, which I think gets to the heart of the book. The struggle is in her mind. She’s fighting fear with creativity.”

Biographical details emerge slowly, through flashbacks and asides. What unifies The Guest Lecture is the seriousness with which it explores Abby’s thinking and the respect it accords to her scholarship. For example, though Abby’s talk about Keynes gets off to a comically bumpy start, at its core is an engaging argument about the nature of economics, the privileged role it plays in measuring success and the importance of maintaining space for utopian ideals.

“Economics contains some of our most powerful cultural narratives,” Riker says. “When we ask, ‘How are we doing as a country?’ we often outsource the answer to a number like GDP. But there’s nothing magical about GDP. It’s just based on criteria that economists set.

“Abby is less interested in what people think than in the way they think,” Riker says. “The book is largely about the stories we tell ourselves — especially the stories that we don’t even realize are stories.”