Train — a tireless and dedicated Chesapeake Bay retriever — never had an official faculty or staff position at WashU, but he took his research work seriously. This July, the Ministry of Ecology and Renewable Natural Resources in the province of Misiones, Argentina, will be unveiling his statue, a testament to his amazing life and contributions to conservation.

A rescue dog who was adopted from the Humane Society, Train passed away in September at the age of 16 (give or take). Still, his legacy continues. In April, the scientific journal PLoS ONE published the latest results of his labors: a study led by his companion and research collaborator, Karen DeMatteo, senior lecturer in environmental studies in Arts & Sciences.

Train’s ability to sniff out key carnivores in the forests of northeast Argentina was crucial for a study of wildlife habitat, DeMatteo says. The study underscored the resilience and adaptability of the carnivores — important indicators of ecosystem health — and helped identify the areas in most critical need of protection. “Train is responsible for 100% of the data,” she says.

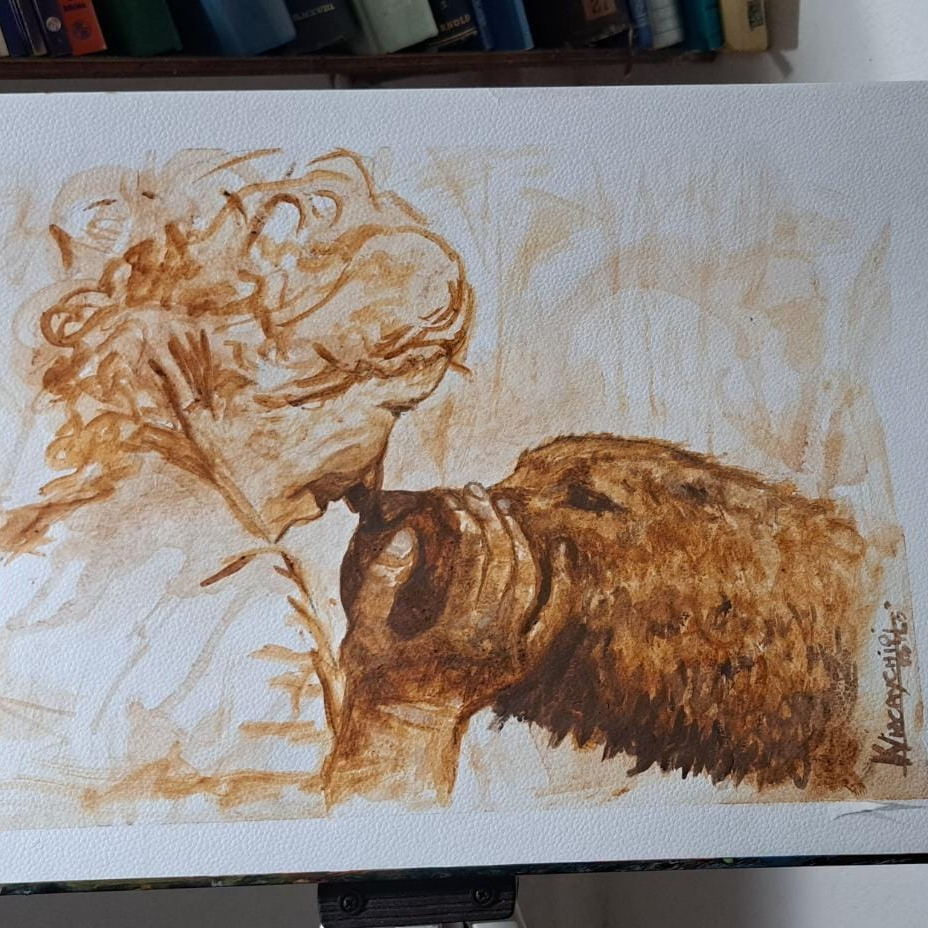

The stocky, shaggy, chocolate-colored dog had a nose for poop. Train and DeMatteo would walk through the forest, DeMatteo with her eyes on Train, and Train with his nose to the ground. He was taught to seek out the scat of five carnivores — pumas, ocelots, jaguars, southern tiger cats and bush dogs — while ignoring the many other smells of the forest. “I never got tired of watching him work,” DeMatteo says. “He was a big, brown machine.” Fittingly, the statue to be unveiled in Argentina shows him sniffing a small pile of animal droppings.

The five carnivores on Train’s list are truly amazing animals, DeMatteo says. Jaguars, pumas and ocelots are familiar to most big cat fans. Southern tiger cats are spotty, sleek and diminutive; a large adult might tip the scales at five pounds. Bush dogs are in the same family as foxes, wolves and domestic dogs, but they have short tails, bear-like faces and squat bodies. They spend half of their days in underground dens and are rarely seen by humans. All five of the target species are vulnerable to habitat loss, and all five are worthy of protection, she says.

The latest study includes data from five research trips between 2009 and 2018. (A planned trip in 2020 was cancelled because of the pandemic.) In that time, DeMatteo walked about 1,000 miles down dirt roads, natural animal corridors and illegal hunting trails cleared by machetes. GPS readings showed that Train traveled about three times as far; in typical dog fashion, he couldn’t follow a straight path.

Train always wore a bell around his neck. The jingling helped DeMatteo find him as he wandered away from the trail, and it served as a warning to the local wildlife. Still, DeMatteo knows they had some close calls. “Sometimes Train would freeze and refuse to go near a riverbank, and I just knew he was trying to tell me that something was down there,” she says. “We’d check it out later, and there would be a giant paw print or a fresh pile of jaguar scat.”

When Train found droppings, DeMatteo would collect a sample for DNA analysis. Very occasionally, the DNA results would point to a fox or another animal outside their scope, but that’s likely because the other animal had contaminated the droppings before Train arrived. “He was never wrong,” DeMatteo says. His reward for a job well done? A belly rub and a little time with a tennis ball.

Detection dogs like Train are an efficient and effective way to find and count elusive animals over large areas — something like a camera trap with legs. His sharp senses identified animals in surprising places. He was able to prove that jaguars were using habitats disturbed by farming, illegal logging and other human activities. “We thought going in that jaguars would stay away from these areas,” she says. Train’s discovery was good news. “It shows that we don’t have to restore thousands of hectares of forest to save the species. But there are some key areas that need to be restored, and we need to protect what’s already there.”

A collapsing economy in Argentina has added new urgency to DeMatteo’s work. She has been working in close partnership with the Ministry of Ecology and Renewable Natural Resources to identify the most critical areas of habitat. With support from the National Geographic Society, she’s also reaching out to another important group in the quest for conservation: local landowners. “We’re trying to find ways to encourage them to not shoot pumas and jaguars that walk through their backyards,” she says.

DeMatteo says that the methods she uses to track wildlife in Argentina could be effectively employed elsewhere. Train himself had six separate trips to northwest Nebraska looking for signs of mountain lions. Because he already knew the smell of the South American puma (the same genus and species), he didn’t need to be retrained.

Train’s last work trip was in Nebraska in 2019. He spent the next few years in contented retirement, enjoying lots of swimming and all the tennis balls he wanted. DeMatteo is currently looking for another dog who can continue his research, but she knows Train can never be fully replaced.