When teaching about cognitive illusions, Henry “Roddy” Roediger, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences in Arts & Sciences, often begins by asking students to read the following sentence while counting the number of times the letter F appears.

Try it yourself:

Finished files are the result of years of scientific study combined with the experience of many years.

How many times did you see an F?

If you answered three, you’re in good company. More than 60% of respondents spot the letter F in the words “finished,” “files” and “scientific.” The correct answer, however, is six. Most people’s brains skip the letter F in the word “of.” In a separate exercise, students who see a list of 15 words including “bed,” “yawn,” “dream” and “slumber”will reliably remember viewing the related (but absent) word “sleep.”

“We’re inference machines,” says Roediger, constantly taking mental shortcuts as we navigate the world. In most cases, this tendency helps us quickly make decisions and solve problems, but it also creates some uncomfortable realities about the fallibilities of perception and memory.

Humans see things that are not there. We remember events that never happened. And even if everyone sees the same thing, we may all be wrong.

In the seminar “Selected Topics in Learning & Memory: Cognitive Illusions,” Roediger walks a small group of advanced students through each of these phenomena. In addition to leaning into his expertise on the science of memory, he also assigns articles covering the latest research on other cognitive illusions — including studies he hasn’t yet read — and asks students to present on the material. Learning together is a powerful teaching tool, Roediger believes.

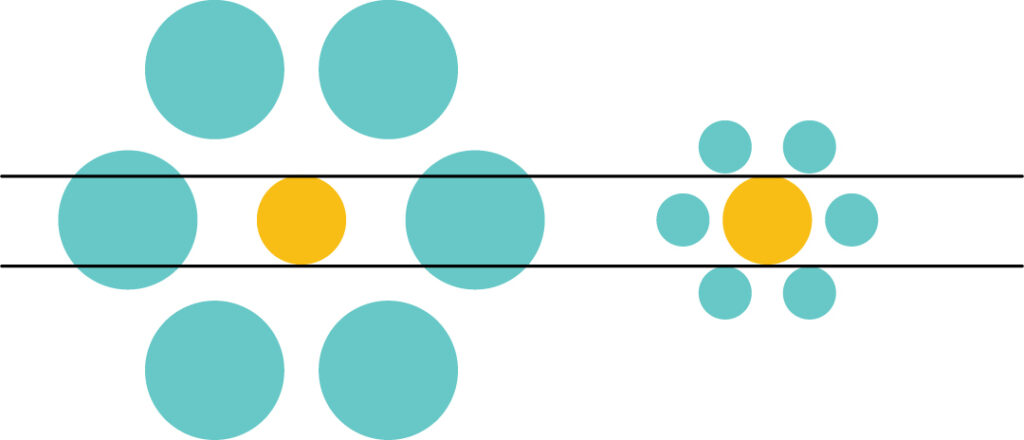

Tricks in visual perception can seem like little more than a fun group activity. Viewers’ reactions range from incredulity to delight when viewing the classic Ebbinghaus illusion, for example, in which it seems impossible that two spheres of equal size are truly the same. In Roediger’s course, students learn about the more serious consequences of such cognitive errors.

The justice system provides salient, and sadly common, real-world examples. Since 1989, the Innocence Project has used DNA evidence to exonerate 375 wrongfully convicted prisoners, 21 of whom served time on death row. Nearly 70% of the cases involved eyewitness misidentification.

“The legal system often has unrealistically optimistic assumptions about cognition,” Roediger says. “Perceiving and remembering often seem easy and error-free, but they can actually be difficult and error prone.” Environments of high stress and low lighting, like some crime scenes, can further increase the likelihood of mistakes in perception and recall.

Of course, illusions are not all bad. Roediger points out that the motion we see in movies and television shows is an illusion. When you watch a show on your computer, the changing images are simply pixels appearing and disappearing, creating an illusion of movement that drives us through the show.

Most of Roediger’s students do not intend to work in the criminal justice system or pilot airplanes (another field in which cognitive illusions can lead to deadly outcomes). However, he believes that professionals in all fields can benefit from awareness of such illusions — even if, or perhaps because, they’re so inevitable.

“I’ve seen some of these illusions hundreds of times, and I still see them the same way,” Roediger says. “It doesn’t matter that you know it’s not true. You can even tell people about the illusion ahead of time, and it’s still there.”

In the same way, Roediger says, humans will always make inferences and go beyond the information given. It’s one of the reasons a group of colleagues can go to the same meeting and come away with very different understandings of what was discussed. Our background knowledge and beliefs can shape our comprehension.

Understanding the ubiquity of cognitive illusions, coupled with in-depth knowledge about how and why such errors arise, can provide students empowerment through humility. Especially when approaching a major decision or when tempted to discount the experience of another person, Roediger says it’s advisable to occasionally reassess thinking, reexamine evidence or just stop and consider the possibility that, just maybe, it’s your mind that’s been tricked.

Recommended reading