On Feb. 22, 1853, Missouri Gov. Sterling Price signed a Charter that brought Eliot Seminary, the institution that became Washington University, into existence.

With the following 17 decades came new names, the construction and near-constant improvement of multiple campuses, and dazzling growth in size, prestige and productivity. Our history also happens to include many moments in which the number seven plays a starring or supporting role. Discover a few significant sevens as a window to WashU’s many milestones from the last 170 years:

17 directors

Washington University’s founding document included a list of 17 names. Alongside Wayman Crow, the state senator who dreamed up and wrote the Charter for the new institution, and William Greenleaf Eliot Jr., the Unitarian pastor who served as its educational visionary and long-term president, the first directors of Eliot Seminary included a wine manufacturer, a wholesale grocer, two lawyers and a railroad president, among others.

As the WashU and Slavery Project documents, several of the directors’ business interests benefited from racial exploitation. Just two of the group, Eliot and U.S. District Judge Samuel Treat, held college degrees. But they all shared a vision for creating educational opportunities in St. Louis. Treat called the fast-growing West “a seething caldron into which so many ingredients have been thrown.” Through their efforts, the group hoped to bring skills and civility to the region.

17th and Washington

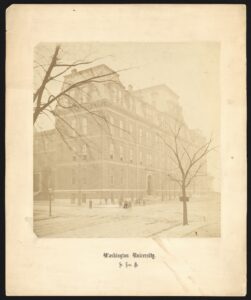

Before relocating to what is now the Danforth Campus in 1905, Washington University took shape in downtown St. Louis. The first university building, called Academic Hall, opened for classes at 17th Street and Washington Avenue in September 1856. Before that point, evening classes were held in a building owned by St. Louis Public Schools.

Rather than educating college-age students, instructors at Academic Hall welcomed boys as young as 10 years old. Following an eight-year program of study that included Latin, Greek, German and French, the students would be prepared to enter Washington University’s collegiate and scientific departments, which were then in development under the guidance of William Greenleaf Eliot.

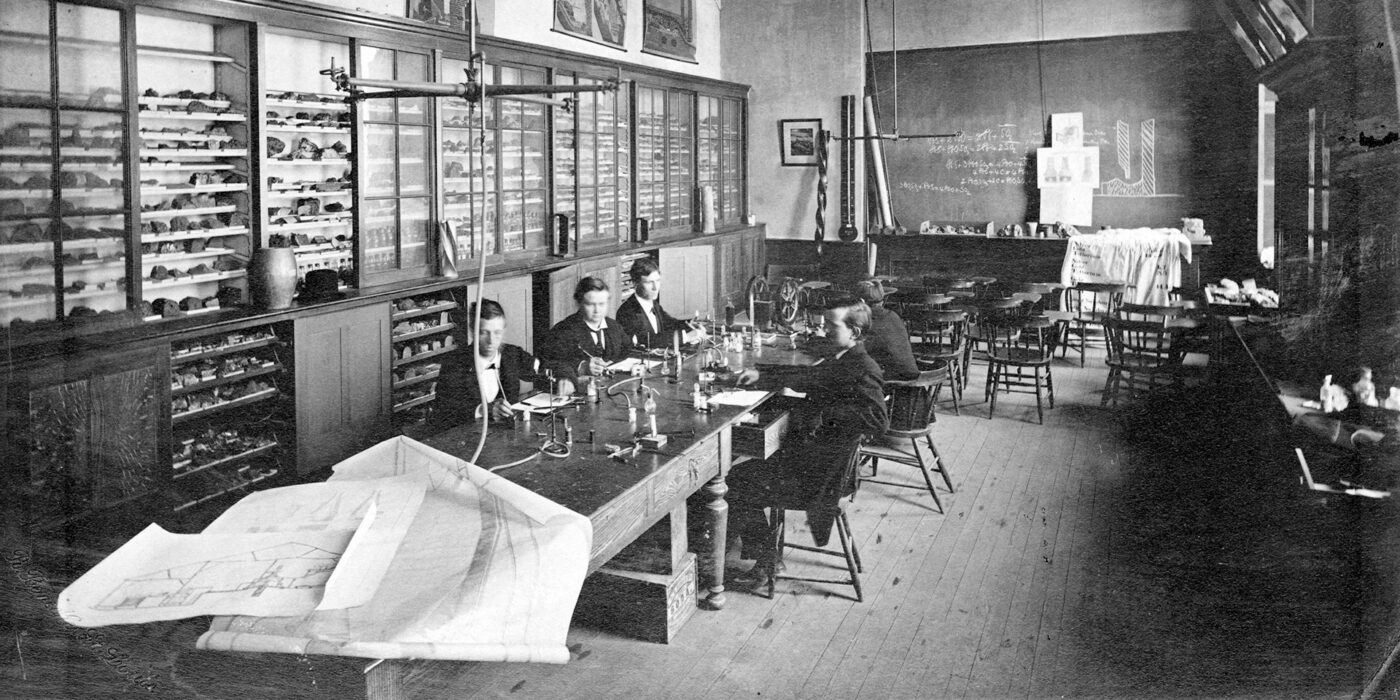

The university’s second building, also at 17th and Washington, housed a laboratory for the scientific department’s first faculty member, Abram Litton. A mile away, the St. Louis Medical College at 7th and Clark would eventually become the medical department of Washington University.

A ladder to Room 107

When William G.B. Carson, AB 1913, AM 1916, performed in the drama group Thyrsus his sophomore year, he had more to worry about than memorizing his lines. Thyrsus’ first theater, Room 107 of Cupples II, had no men’s dressing room. In order to enter the 16-foot stage, Carson and his fellow performers had to dress down the hall, run outside, climb a ladder and crawl through a window — a feat that became even more challenging in the rain.

“There was mud on every rung of the ladder,” recalled Carson, who later became a WashU faculty member. “As I descended to the earth after my brief act, the tails of the dress-suit (my first) in which I was arrayed suffered damage from which they never recovered.”

In addition to monthly performances at the so-called Thyrsus Theatre in Room 107, Thyrsus held elaborate annual productions at the 1,200-seat Odeon Theatre on North Grand Avenue. In 1916, they produced the film “The Maid of McMillan,” which is now available online thanks to the preservation efforts of Washington University Libraries.

Thyrsus still performs today, making it one of the oldest student theater groups west of the Mississippi.

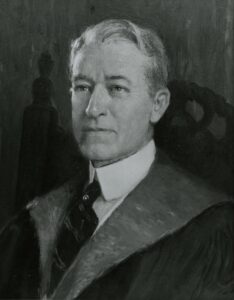

Herbert Hadley, seventh chancellor

Washington University’s 15 chancellors have each shaped the course of the university over its 170 years, and Herbert S. Hadley was no exception. Though Hadley only led the university from 1923–27, several notable programs began during his tenure.

In 1927, shortly before stepping down due to his heath, Hadley presided over the founding of the George Warren Brown Department of Social Work. The Graduate School of Economics and Government, which eventually became the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., also started under Hadley. The same goes for the departments of economics, political science and sociology.

As the former governor of Missouri, Hadley had a particularly glowing view of WashU’s home city, St. Louis.

“Ours is the typical American city…that belongs neither to the East, West, North, or South, but which exemplifies American life as a whole,” he said. “Here are to be found the culture and refinement of the East, the courage and vigor of the North, the frankness and freedom of the West, and the courtesy and chivalry of the South.”

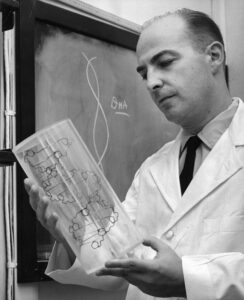

The seventh (and eighth) Nobel laureate(s)

An impressive 26 Nobel laureates have ties to Washington University. The seventh WashU-affiliated Nobel, however, is a bit of a toss-up. In 1959, Arthur Kornberg and Severo Ochoa shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work discovering the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). Both scientists held affiliations with WashU’s School of Medicine.

In the early 1940s, Ochoa served as an instructor and research associate in pharmacology, where he worked with future Nobel winners Carl and Gerty Cori. Kornberg chaired the Department of Microbiology from 1952–59.

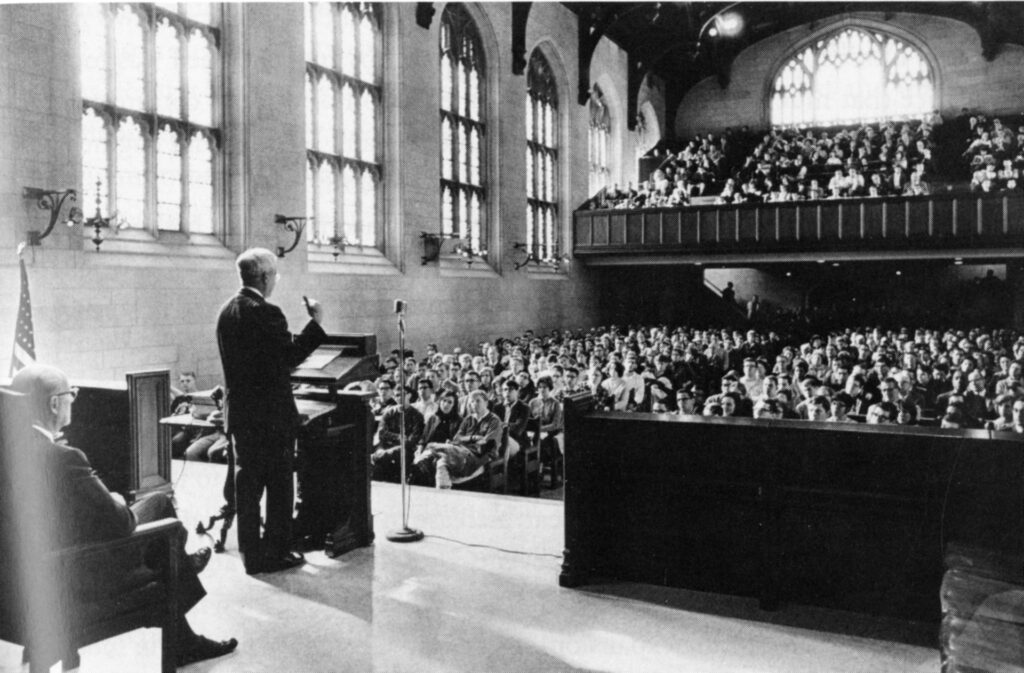

“Seventy by Seventy”

On a cold afternoon in February 1965, a crowd gathered in Graham Chapel to hear Chancellor Thomas Eliot make an announcement “of great importance to the university.” At the convocation, Eliot officially opened the “Seventy by Seventy” Campaign. As the name suggested, the fundraising initiative aimed to raise $70 million by 1970.

In the years leading up to the campaign, growth in faculty numbers and academic programs had already led to major increases in university spending. Eliot understood that such growth required substantial fundraising, and he sought to balance the books and “complete the emergence of Washington University as a major national center of higher learning.”

The campaign was ultimately successful in hitting its $70 million goal, but there were bumps along the way. Unrest over the Vietnam War arose at WashU and around the country in the late 1960s, capturing the attention of students and administrators. And the $70 million raised still left the university in substantial financial need, a cause that would be taken up by Eliot’s successor, William H. Danforth.

Double wins in 2017

Including the men’s track and field title earned last year, WashU has scored 24 NCAA national championships in its history. The women’s track and field team earned two of those titles in 2017, when the Bears proved victorious at both the indoor and outdoor D-III championships. The same year, WashU goalie Lizzy Crist was named NCAA Woman of the Year on the heels of the women’s soccer team’s 2016 national championship.

Female scholar-athletes have a notable history of success at WashU. The women’s volleyball team holds 10 national titles, including an unbroken streak of championships from 1989–96.

An Apollo 17 connection

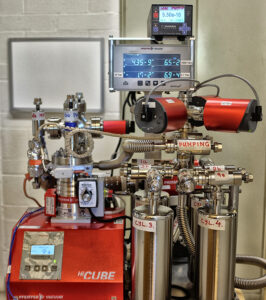

WashU’s research activities span the globe and even go beyond Earth’s atmosphere to outer space. As part of the Apollo Next Generation Sample Analysis initiative, scientists in the departments of physics and Earth and planetary sciences are helping to recover gases from a container of lunar soil that Apollo 17 astronauts collected on the surface of the Moon more than 50 years ago.

The WashU researchers designed and built the extraction manifold apparatus used at NASA’s Johnson Space Center to carefully open the vacuum-sealed containers in 2022. Information gathered from the samples will help inform NASA’s Artemis missions, an effort that Brad Jolliff, the Scott Rudolph Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences and director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, sees as essential for the next generation of space exploration.

To learn more about the history of Washington University in St. Louis, see “Beginning a Great Work: Washington University in St Louis 1853–2003” by Candace O’Connor and “Washington University in St. Louis: A History” by Ralph E. Morrow.