For Mary Bartling, MLA ’10, DLA ’18, banned books serve as thought catalysts. “All books make you think,” she says, “but banned books make you think the most.”

Bartling’s website, ThisBookIsBanned.com, was established in the spring of 2021. It functions as an online literary community, extending beyond any superficial, plot-centered approach toward books and “into the art” of reading.

“Books are written for a myriad of reasons,” she says, and while entertainment is one of them, for Bartling, it is not the most important. “Reading is about expanding our idea of what the world is and how we can go about changing it,” she says.

By providing a close analysis of books that have been banned from schools or libraries, Bartling’s website highlights the contexts necessary for understanding certain texts on a deeper level. For example, “A female writer in the 18th century is going to hold a different perspective than a female writer in the 1970s,” she says, noting that that shift in perspective can yield entirely different meanings and interpretations of a given text.

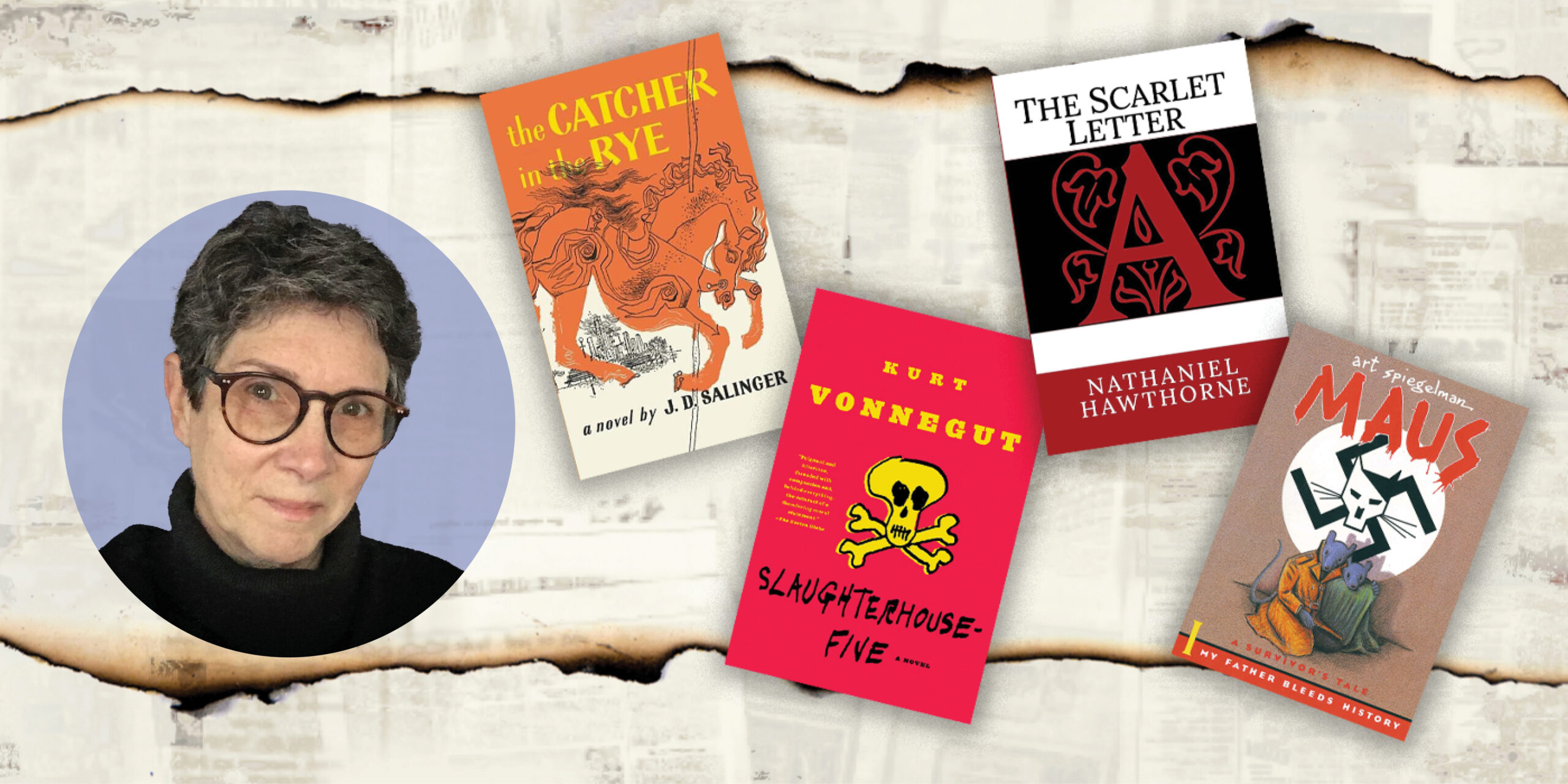

A recent essay by Bartling speaks of a notoriously banned book, The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger’s work contains no innately dangerous ideas, but “it challenged the status quo in an era defined by conformity,” Bartling says. Salinger critiqued patriotism, the education system, and religion, not because he neglected these ideals but because he cared enough to improve them — extending the barrier of what was previously thought imaginable.

Often banning a book means increased sales. (As Mark Twain famously said to his publisher after The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was banned, “That will sell 25,000 copies for us, sure.”) But banning any book remains dangerous, Bartling says, because “the people who most benefit from reading it are denied that possibility. Art may be subjective, but our ability to see it shouldn’t be.”

Toni Morrison, an inspiration for Bartling, once said that banning books is an “elementary kind of censorship designed to appease adults rather than educate children.” Bartling adds to this sentiment: “When parents ban books,” she says, “they feel like they’re being protective, but they’re just restricting thought and limiting a child’s ability to navigate in the world.”

“I might not be able to live in a different neighborhood or a different country, but I can read books that address those things. It’s through these new insights and perspectives that we can become better global citizens.”

Mary Bartling

Ultimately, Bartling hopes her site will be utilized as a teaching tool for middle school and high school teachers, reinforcing her belief that “access to a top-tier education should always be free and accessible.”

At the heart of Bartling’s site is perspective itself. Exposing ourselves to other people’s perspectives is “just being an empathetic human being,” she says. “It’s how we come into contact with things we’ve never thought about before. But the practice of banning books inhibits constructive conversations about the most relevant issues of our day.

“I might not be able to live in a different neighborhood or a different country,” Bartling says, “but I can read books that address those things. It’s through these new insights and perspectives that we can become better global citizens.”