When a patient comes into an emergency room with a gunshot wound, the No. 1 priority is to save a life, by whatever medical procedure necessary. But the impacts of violence go beyond what emergency medical care can address, and treating physical injuries alone does little to disrupt the cycles that perpetuate violence within communities.

The Life Outside of Violence program (LOV), launched in 2018 by Washington University’s Institute for Public Health, offers comprehensive support to people who’ve experienced violence, and it aims to decrease incidences of retaliation, re-injury and death. LOV takes an individualized approach for those who’ve been harmed by offering mental health services and connecting participants to resources and agencies for education, employment, medical and housing assistance.

Born out of the university’s Gun Violence Initiative that began in 2015, LOV is the first city-wide hospital-based violence intervention program in the nation. The program collaborates with four trauma centers (BJC HealthCare’s Barnes-Jewish Hospital and St. Louis Children’s Hospital and SSM Health’s St. Louis University Hospital and Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital) and three research universities (WashU, Saint Louis University and University of Missouri-St. Louis). The joint effort has broadened the reach of assistance and has allowed LOV stakeholders to get a bigger picture on how violence and its aftereffects impact the city.

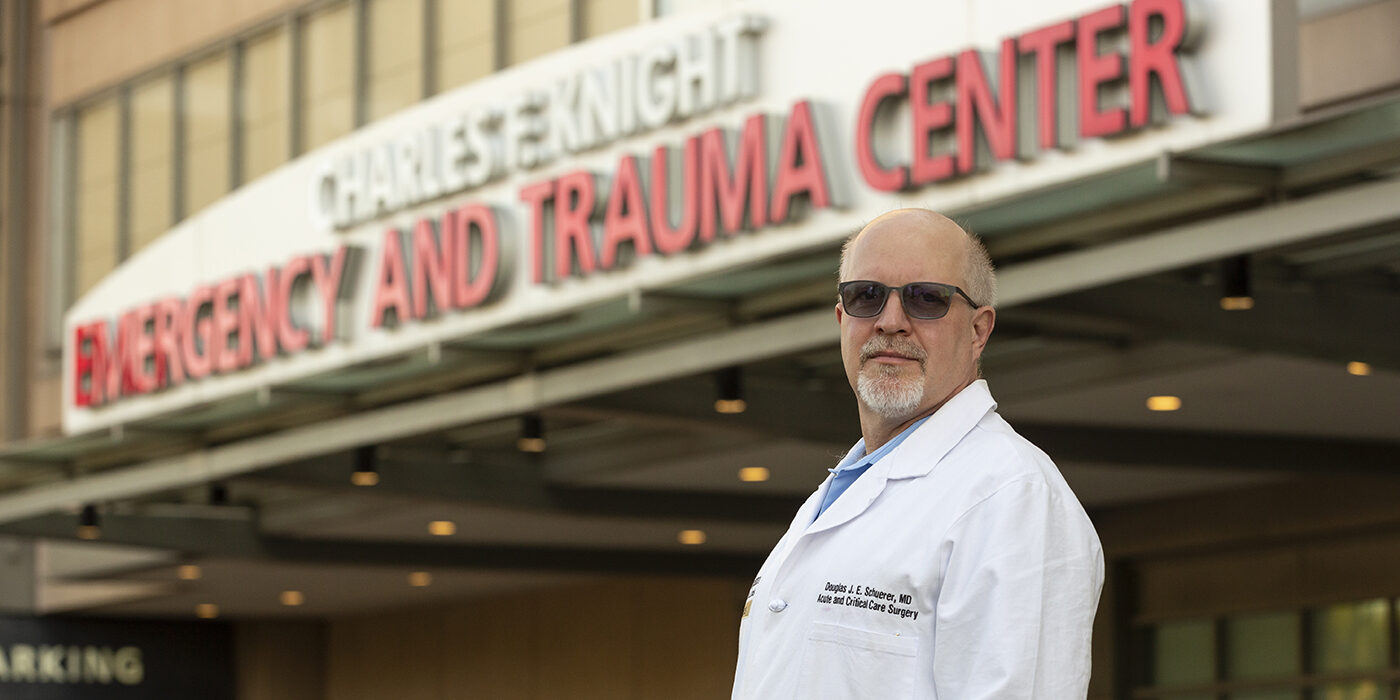

“By collaborating among hospitals citywide, we have a more robust program, and we’re able to track and understand the patients and outcomes a lot better than any single institution,” says trauma surgeon Douglas J. E. Schuerer, MD, professor of surgery at the School of Medicine, director of trauma at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and a founding board member of LOV. Those numbers include not just how many people are subject to violence in the city, but how often they end up back in the hospital following another violent incident.

“By collaborating among hospitals citywide, we have a more robust program, and we’re able to track and understand the patients and outcomes a lot better than any single institution.”

Douglas J. E. Schuerer, MD

By some estimates, nearly 60% of people who have experienced violence-related trauma in the U.S. wind up returning to the hospital, known as recidivism, following subsequent encounters with violence. Incidents of retaliation are a major driver of recurrent violence, and mortality rates may be as high as 20% within five years for those who initially survive violent trauma.

LOV has seen dramatically lower rates for patients who have received the program’s comprehensive support, achieving its goal of less than 10% recidivism within its first three years of operation. And in an extraordinary mark of the program’s effectiveness, there have been no incidents of retaliation or mortality among the enrolled participants.

“The LOV program has been very important to us as providers because we’re finally starting to affect injury prevention in and around the area of interpersonal violence,” Schuerer says. “That’s been one of the hardest areas to address.”

Meeting patients in the moment

LOV is available for patients between the ages of 8 and 30, and the program works with participants for up to a year. The LOV team receives real-time alerts when people who have experienced violence are admitted to St. Louis–area hospitals, and the intervention process begins soon afterward. Connecting with patients and their loved ones in the moments immediately following a violent trauma is crucial to the effectiveness of the program.

“There’s an important window of opportunity when you’re seeing someone who has maybe survived a near-death experience, and the psychological impact of that,” says Kateri Chapman-Kramer, LOV project manager. “We want to engage people in services at that moment and offer comprehensive support that goes beyond their stay in the hospital.”

“There’s an important window of opportunity when you’re seeing someone who has maybe survived a near-death experience … We want to engage people in services at that moment and offer comprehensive support that goes beyond their stay in the hospital.”

Kateri Chapman-Kramer

Members of the LOV team begin by offering patients and their families help with their immediate needs, including safety concerns and managing the mental health impacts and other ripple effects of a violent trauma. LOV’s team are from the communities being served, and members have direct experience with violence, either personally or from the loss of a loved one. “They can take the approach of saying, ‘I’ve been where you are,’” Chapman-Kramer says.

Those who enroll in the LOV program are connected to a case manager, who becomes their point of contact for comprehensive support, including managing continued medical care and helping build a life outside the cycle of violence. LOV case managers meet with participants in their homes or wherever they feel most comfortable, developing a relationship and building trust. “From a therapeutic standpoint, rapport building is key,” says Brown School alum Melik Coffey, who earned an MSW in 2011 and is an LOV clinical case manager at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital. “We also work to normalize the crisis piece of it, assuring patients and their families that what they’re experiencing is to be expected.”

Support beyond healing

LOV provides participants with resources needed to forge a path toward recovery, which includes consideration for the psychological impacts of experiencing violence. “Our participants are connected from day one with mental health support, and we utilize a trauma-informed approach,” Coffey says. “Whatever the situation, whether we’re trying to get them housing or be their advocate, they have somebody who can help them navigate these different systems,” says Coffey, noting that special attention is paid to how trauma has impacted their mental well-being.

The first three months of the program are typically focused on building rapport with participants and assessing what is needed to make a comprehensive recovery. Once an individual’s physical injuries are managed, the next phase generally involves more intensive therapeutic support, providing participants with tools and coping mechanisms to move forward, including connecting them with tutoring or resources to assist with college or job applications.

Perhaps most important for long-term recovery, LOV case managers aim to help participants recognize that the impacts of trauma are complex and take time to work through. “We want to help them understand what’s going on with their mental health, normalize that, and put coping tools in place,” Coffey says. “In order to disrupt this cycle of violence, we have to wrap our arms around that person and their support network.”

A future for violence prevention

After a three-year pilot funded by the Missouri Foundation for Health, LOV has secured additional grants, including from the U.S. Department of Justice, and has commitments from participating St. Louis–area hospitals to sustain the program for at least another two years. The future of LOV depends on continuing to demonstrate its benefits to the city’s medical systems and to the people within the communities it serves.

“We’re trying to show that it works and that it’s cost effective,” says Schuerer, of the program’s significant success rate, which has clear benefits for participants and also saves hospitals resources by driving down recidivism. “The hospitals themselves can support the program with the return on investment,” Schuerer says.

Encouraging more individuals who experience violence to enroll in the program will also be key to its longevity. “It’s important for us to demonstrate the benefits of the program to the community, to foster more trust toward the medical system,” Schuerer says. That means continuing to build partnerships with community leaders and organizations to spread the word about the LOV program and its lasting impacts on participants.

“We’re pushing to help people understand that other futures are possible,” Coffey says, “and that they can be agents for positive change in the community. But we need to have these conversations.”

“We’re pushing to help people understand that other futures are possible, and that they can be agents for positive change in the community. But we need to have these conversations.”

Melik Coffey