Often referred to as an “education within an education,” the Assembly Series lecture program remains one of the most fondly remembered aspects of the Washington University experience.

For 70+ years, the Assembly Series has welcomed leaders and visionaries, pioneering scientists, public intellectuals, genre-breaking artists and performers, Nobel Laureates and Pulitzer Prize winners, Supreme Court justices and entrepreneurs. Moreover, these lectures have been recorded, going as far back as 1949, preserving the ideas shared on campus for future generations and resulting in a one-of-a-kind archival collection. But in recent years, the very survival of this academic treasure trove had been in question.

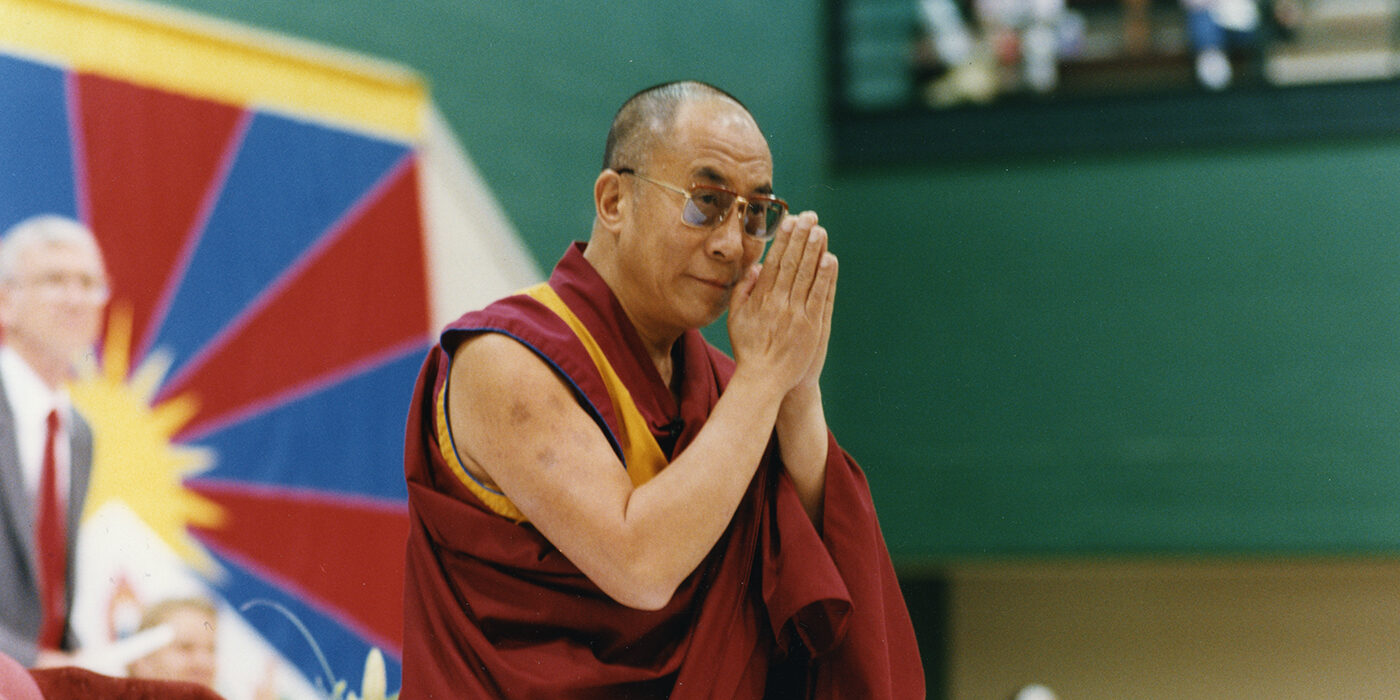

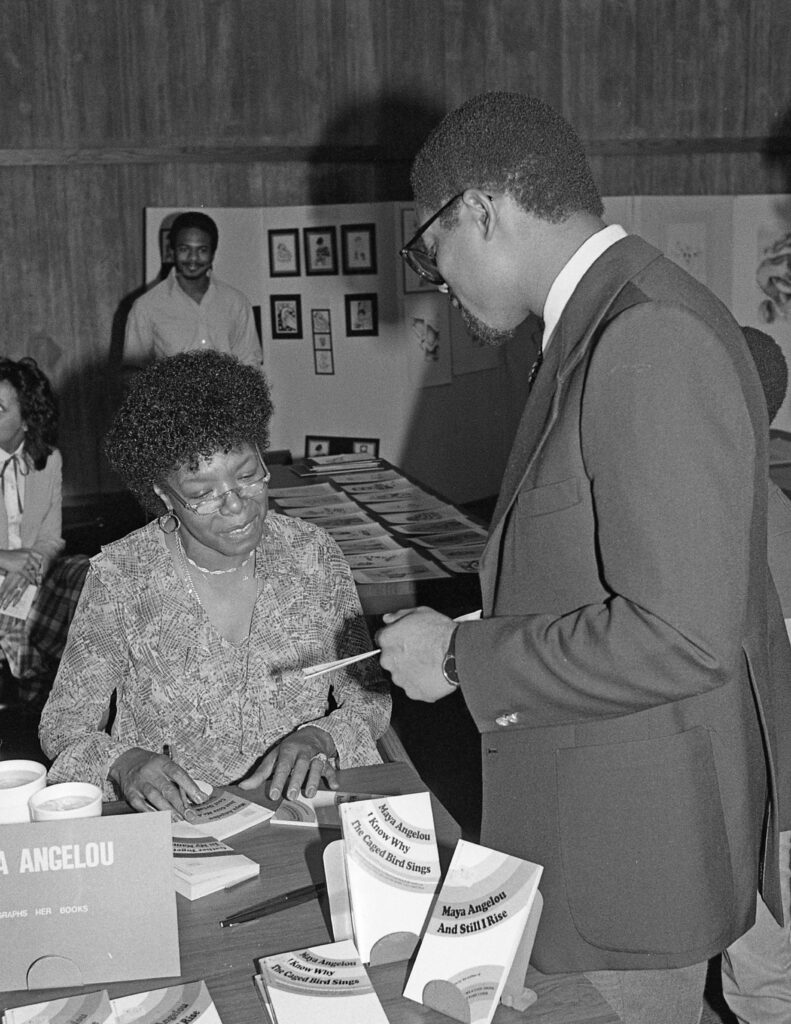

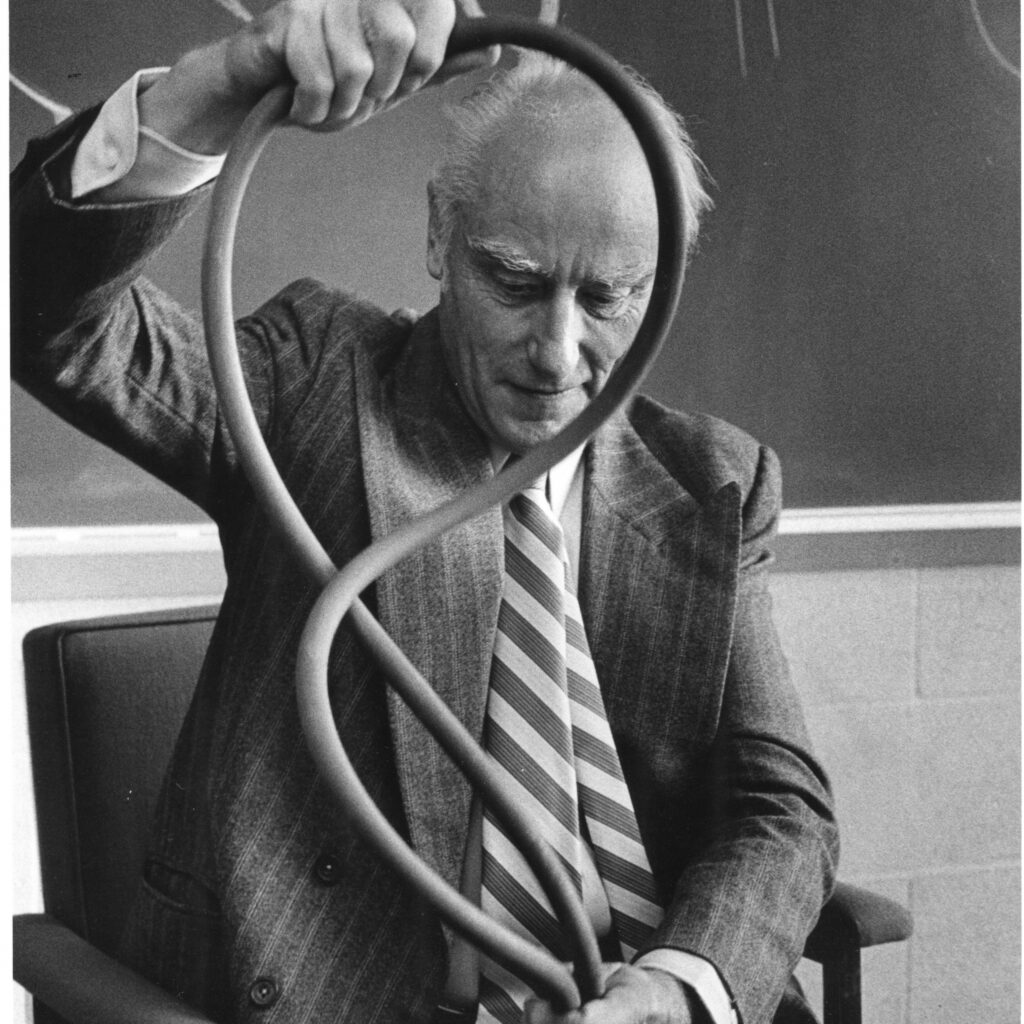

Like a fading memory, earlier lecture recordings, on magnetic reel-to-reel and cassette, were deteriorating. Despite University Archives keeping them in a vault, where temperature and humidity were strictly monitored, some of the oldest tapes were giving way to vinegar syndrome — where acetic acid and a vinegar-like odor are given off as acetate decomposes. Impartations from the likes of Maya Angelou, Jimmy Carter, Arthur C. Clarke, Francis Crick, the Dalai Lama, Jesse Owens and hundreds of others would inevitably be lost to time. In total, more than 1,400 recordings on magnetic media were largely inaccessible to the public.

“The thought of losing this tremendous collection that impacted generations of students was devastating,” says Sonya Rooney, university archivist. “Not only would this mean losing the documentation of this university tradition, but it would also mean future researchers would not be able to experience the historical snapshots the Assembly Series lectures provide.”

Archival aspirations become reality

From the outset of her tenure as university archivist in 2005, Rooney had wanted these historical recordings made accessible to the WashU community through digitization, but it was going to take a huge, and costly, effort. “With the older reel-to-reel tapes, we couldn’t play the originals because we were worried about their condition,” Rooney says. “It’s been an ongoing question of how researchers could access this material more broadly.”

“CLIR’s grant helped us digitize them all at once, preserving them and removing the barrier to accessing these recordings.”

Sonya Rooney

In 2022, Rooney’s archival aspirations became a reality, thanks to a $34,520 award from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) and thanks to numerous University Libraries’ staff involved in making the project a success. Over the course of the grant, the original recordings were sent in six batches to Preserve South, an audiovisual digitization lab based in Buford, Georgia. And all surviving Assembly Series lectures up to 2008 — when digital audio became the standard — were brought into the present, and the foreseeable future. “CLIR’s grant helped us digitize them all at once, preserving them and removing the barrier to accessing these recordings,” Rooney says. (After 2008, lectures were on CDs and DVDs, and University Libraries also digitized these recordings to make the entire collection accessible.)

Now that the lectures are digitized, University Libraries can also move forward with publicizing this unique collection. An online exhibit, “Echoes of Voices Past,” will celebrate the grant by highlighting the Assembly Series and the impact it had on those who attended. “If you look at the breadth and the number of speakers and the different topics that are covered,” says Rooney, “it’s so diverse and interesting to so many different people.” When it opens, the exhibit will include 15 speakers (with audio excerpts) as snapshot examples and will provide the entire list of recordings in the archival collection, underscoring the significance of the grant — part of CLIR’s Recordings at Risk initiative — in preserving this crucial aspect of WashU history and tradition.

In addition, a one-hour virtual event at 4 p.m. (CDT) Nov. 3 will focus on the impact Assembly Series has had on the WashU community across the years. Henry Schvey, professor of drama; alumnus Rob Wild, AB ’93, associate vice chancellor for student affairs, dean of students and chief of staff; and others will share memories of the Assembly Series, and the grant’s importance will be discussed.

Looking back, looking forward

These archival recordings also yield exciting prospects for future research. As both graduate and undergraduate studies increasingly allow for multimedia resources to complement text-based sources, these recordings offer insight into not only speakers’ subject matter, but also their voices, the conviction and passion by which their ideas were conveyed, and the audience reactions to their lectures. Going far beyond what a transcript can provide, each recording is the reflection of a person and a moment.

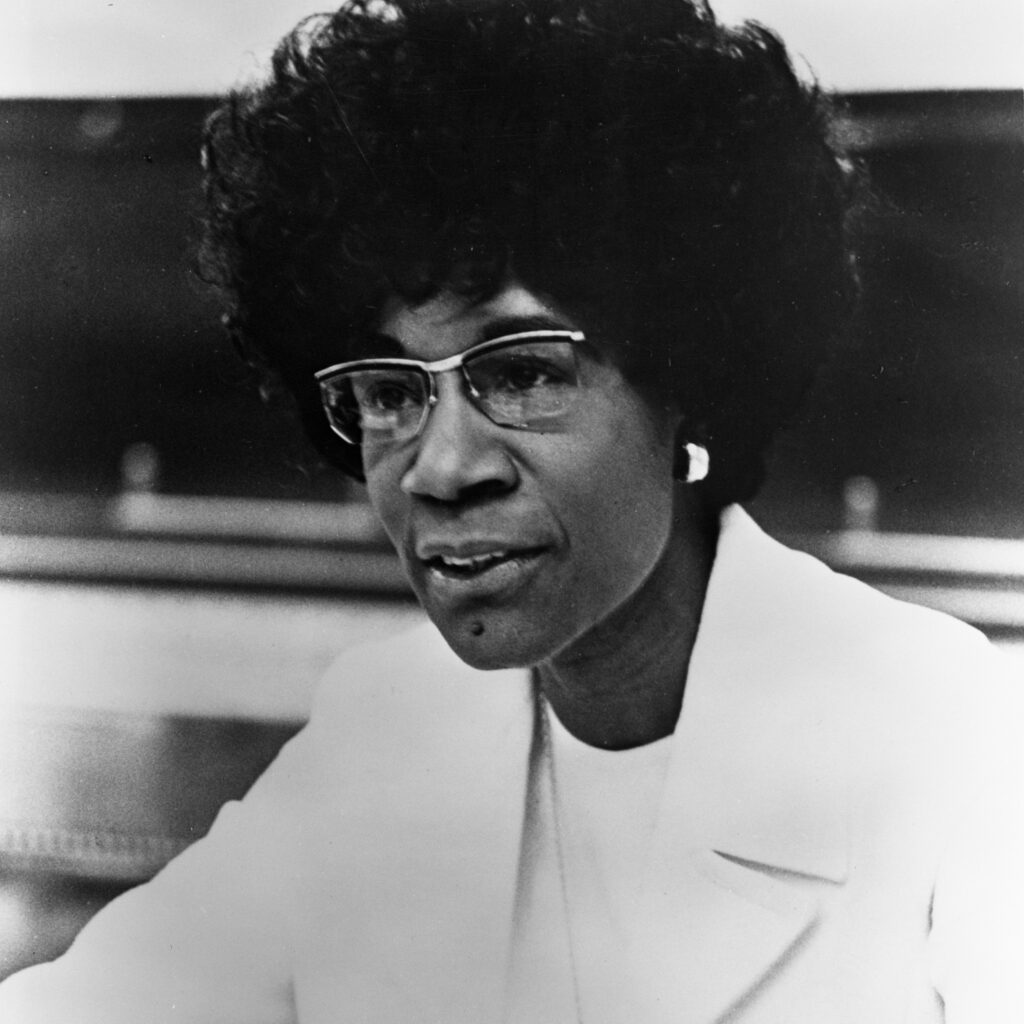

The lectures also illustrate how ideas progress over time. For example, perspectives on the topic of gender equality can be gained from the WashU lectures of Betty Friedan, bell hooks, Mae Jemison, Barbara Jordan, Sandra Day O’Connor, Eleanor Roosevelt, Gloria Steinem and many others.

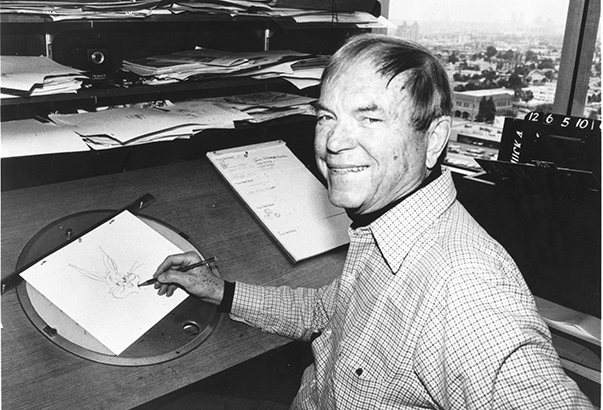

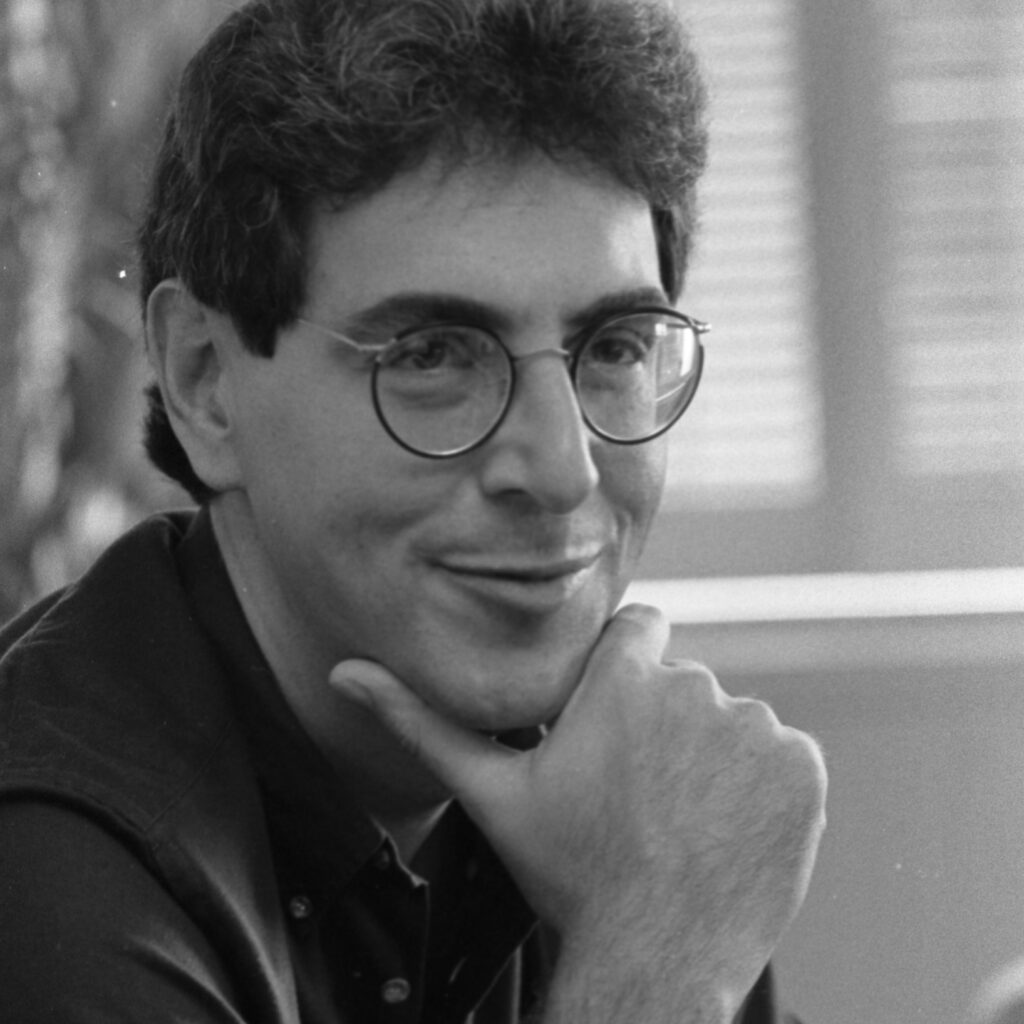

This newfound access to seven decades of lectures also opens a window into university history, as the Assembly Series frequently included addresses by WashU chancellors, from Arthur Holly Compton and Thomas H. Eliot to William H. Danforth and Mark S. Wrighton. WashU faculty past and present, such as religious scholar Huston Smith; authors William Gass, Wayne Fields and Gerald Early; biologist Ursula Goodenough; economists Murray Weidenbaum and Nobel Laureate Douglass North; and political scientist Lee Epstein, among others, are part of the collection as well. Alumni such as Harold Ramis, A.E. Hotchner and Mike Peters also delivered Assembly Series lectures.

Joy Novak, AB ’03, head of Special Collections in University Libraries, can attest to the revelatory impact these recordings can have. As a student, Novak attended feminist author Rita Mae Brown’s lecture in 2002, which explored gender dynamics and patriarchy rooted in the history of the English language. “As an English and history major focusing on gender studies, Brown’s talk made me realize how these issues were so deeply embedded in everything around me, inspiring me to dive deeper into my own studies,” says Novak, a presenter in the upcoming webinar. “Listening to the recently digitized lecture in 2022, it was fascinating to realize how much the conversations about gender have changed and what issues have persisted over 20 years.”

Having this collection readily available will certainly bring back memories to the WashU community, as students, faculty and staff have all played a role in carrying on this revered WashU tradition. “It was always a collaborative event across the university to bring in these speakers,” says Rooney, “and now having the lectures digitized, we have a wonderful opportunity to serve the university community well into the future.”

“The Assembly Series exposed me to people and ideas I would never have had contact with otherwise,” says alumna Phyllis Wilson Grossman, AB ’66. “Often the things you experience outside the classroom as a student make the biggest difference in your education.”

*Regarding Harold Ramis: “The titles of two of Harold Ramis’ Assembly Series lectures, ‘The Semiotics of Comedy in the Post-Modern Era: Towards a Hermeneutics of Humor’ (2000) and ‘Existentialism, Post-Modernism and Deconstructionism: Will This Be on the Test?’ (2009), speak volumes about the man. He was funny, irreverent and deeply sensitive to the intellectual currents and pretensions of his time. Harold was a dear friend and a great friend to the university, which he graduated from in 1966 and continued to serve as a trustee. Although Animal House, Caddyshack, Vacation, Groundhog Day and other films remind us of his body of work as one of America’s great filmmakers, for hundreds of Washington University students and faculty, it was his Assembly Series talks and the intimate classes he gave to aspiring actors and directors in the Performing Arts Department that define his legacy. Harold was living proof that fame and worldwide recognition need not come at the expense of one’s core values; through all the years I knew him, he remained steadfast in his care of others and to the university that gave him his start as an artist.”

— Henry Schvey, professor of drama