Physician turned internationally renowned biochemist and pharmaceutical executive P. Roy Vagelos, MD, never planned his career path. “Each step led to the next,” he says. “Recognition was never my motivation. I wanted to work where I could be productive and make important things happen.”

Following a decade at the National Institutes of Health, Vagelos joined the faculty of Washington University School of Medicine in 1966 as head of the Department of Biological Chemistry, now called the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics. During his nine years at WashU, he founded two pioneering programs: the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP), combining elements of the MD and PhD programs into a rigorous curriculum for future physician-scientists; and the Division of Biology & Biomedical Sciences (DBBS), a transformative model for interdisciplinary education and research across the life sciences that united WashU’s main and medical campuses. He also was instrumental in recruiting a cohort of Black medical students from historically Black colleges and universities to diversify the student body and advance racial equity in health care.

Vagelos left WashU in 1975 to direct research at Merck & Co., where he eventually became CEO and chairman. Since then, both MSTP and DBBS have risen to top ranks nationwide. Graduates of these lauded programs are advancing medicine and improving health across the globe.

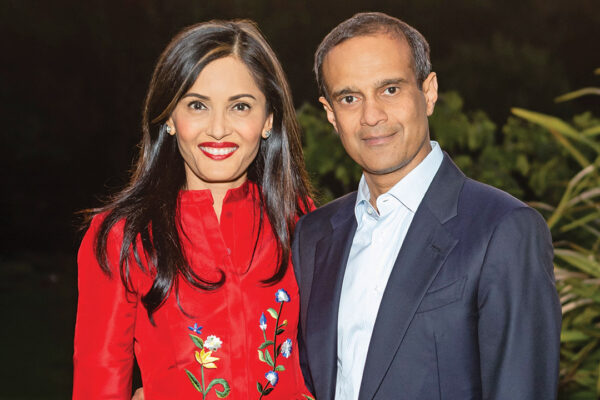

In 2021, Vagelos and his wife, Diana, contributed $15 million to DBBS to fund graduate fellowships and bolster undergraduate programs. Their gift honors the late Chancellor Emeritus William H. Danforth, who recruited Vagelos to WashU, supported his visionary ideas and became a longtime friend. The university renamed DBBS the Roy and Diana Vagelos Division of Biology & Biomedical Sciences in recognition of the couple’s generosity.

How did you become a scientist?

After I graduated from medical school in 1954, I was assigned to the National Institutes of Health to complete two years of required service to the federal government. There, I met Earl Stadtman, a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, who was one of the outstanding biochemists of the world. Although he had never worked with an MD and I had never worked in a laboratory, he agreed to take me on. For two years, he led me through biochemistry. With his encouragement, I stayed at the NIH eight more years, conducting research independently and starting my career as a scientist.

Every successful scientist has had a mentor like Earl, who turned him or her on to science. Colleagues at the medical school and I introduced the idea of giving training and research opportunities to undergraduates through DBBS for this reason. Getting these students into laboratories so that they can participate in real experiments, not just learn from a textbook, is so important. This access sparks an interest in the sciences early on in a young person’s life and helps build the pipeline of future scientists.

How does basic science advance health care?

Nearly every improvement in health care in the last 50 years began with a basic science breakthrough. When a scientist makes a discovery at a molecular level, others leverage that knowledge to learn even more, as we recently saw with messenger RNA and the development of COVID vaccines. Answering fundamental questions about the body and disease is key to identifying therapeutic approaches.

The critical importance of basic science to medicine underlies the role of the physician-scientist, who is both investigator and clinician. Physician-scientists are aware of the potential applications of the science. At the same time, clues from studying disease can open new avenues for research. The two realms are stronger together than alone, which was the impetus for establishing the Medical Scientist Training Program.

Why did the programs you founded at WashU succeed?

We had the world’s greatest faculty — people who were terrific scientists themselves and worked well with students.

In the case of MSTP, WashU was not the first to offer the combined degree program. But we were able to take the lead very quickly because few medical schools had the level of basic science expertise in their clinical departments that we did.

When I arrived at WashU, the six basic science departments recruited their own graduate students with varying degrees of success and did their own teaching. I was confident that we would be more effective together and that undergraduates would benefit greatly from taking courses led by basic science faculty from the med school. Within one year of its creation, DBBS greatly enhanced the quality of the undergraduate and graduate programs in the life sciences. The division also gave grad students the chance to complete their first year before choosing a discipline. To my astonishment, this structure became known as the WashU model, and it remains the standard for biomedical education today.

What impact did WashU have on you?

I come from a very humble background. My parents were immigrants from the small Greek island of Lesbos who only completed sixth grade. I learned everything along the way, beginning with English as a second language so I could go to elementary school.

At WashU, I gained the confidence to implement new ideas and lead an organization. I was able to continue building the strong biochemistry department and to start several programs that were new and different. Although I didn’t know it then, what I learned and accomplished at WashU prepared me for leadership.