When Jason Green, AB ’03, was growing up in Gaithersburg, Maryland, he knew he’d go to college, but his mother’s only caveat was that he attend a college east of the Mississippi.

How he landed at Washington University in St. Louis — 7 miles west of that big river in the middle of the country — is a good story. So is how, at the age of 28, Green landed in the Obama White House as associate general counsel after serving as the campaign’s national voter registration director — while still managing to get a law degree from Yale. So is the story of how the White House lawyer became a tech entrepreneur and documentary filmmaker. And the story of how that documentary, Finding Fellowship, took more than 7 years to make and has now led him back to the community where it all started.

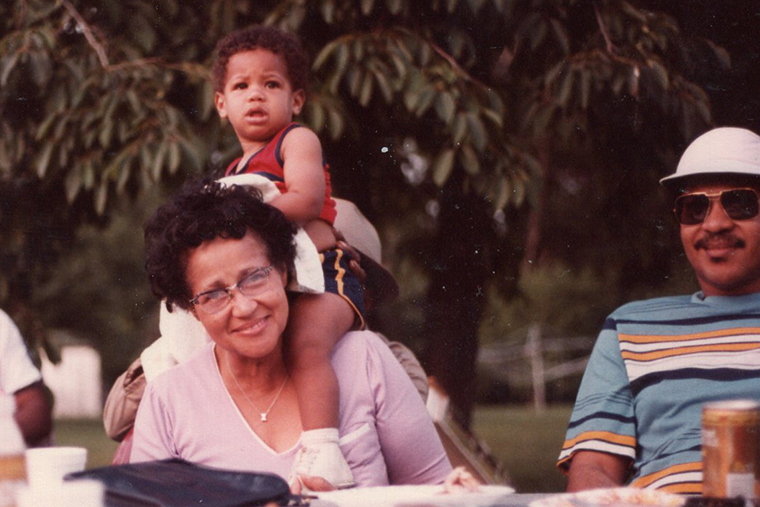

But Green’s story begins much earlier, in the early 1980s, when he’s a 5-year-old accompanying his grandmother, Ida Pearl Green, to the local hospital where she was a volunteer. It’s the origins of a story that in many ways has defined his life, a living example of the power of both words and deeds.

“He was … so concerned … his family understand his love and respect for them. It made the film a more profound experience.”

Wayne Fields, the Lynn Cooper Harvey Distinguished Chair Emeritus in English in Arts & Sciences

“She showed me how you can make someone’s life better, more equitable, more dignified simply by being present,” Green says of his grandmother, who is now 104. “And I just kind of knew that was the walk I wanted to be on. I don’t end up being an aide to President Obama if my grandmother doesn’t open my eyes to the capacity of service when I was 5, volunteering at a hospital with her.

“Fast forward many years, she happens to be 95 years old in that same facility, and we don’t know whether she’s going to come out,” Green recalls. “It just made sense that I come home to sit with her and hold her hand in the same way I saw her hold so many others’ hands. And in that time, she shares this story with me that, frankly, I’d been too busy to hear for 30 some years.”

A personal story

That story is the heart of Finding Fellowship, a 57-minute documentary film of how three racially segregated churches — two white congregations and one Black — came together in rural Maryland in the late 1960s in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and how the three churches have stayed together for more than 50 years.

It’s a story inspired by the community in which Green grew up, and it stars the cast of characters that molded him and his sisters, including his grandmother; his parents; and members of the rural Maryland community connected with his family’s church, Fairhaven United Methodist.

But before there was Fairhaven, there were three other churches. And this was the story Jason Green, the White House aide, finally slowed down long enough to hear: By the late 1960s, it was becoming apparent that these three rural, segregated congregations lacked the financial resources to survive on their own, and the very night the Black church gathered to discuss a potential merger was April 4, 1968. One of the film’s many dramatic moments occurs early on with the description of how the news of the King assassination was disseminated, a report on the radio that many were hearing just as they were arriving to the meeting. At a loss for what to do, the community members did the only thing they knew for sure how to do: pray.

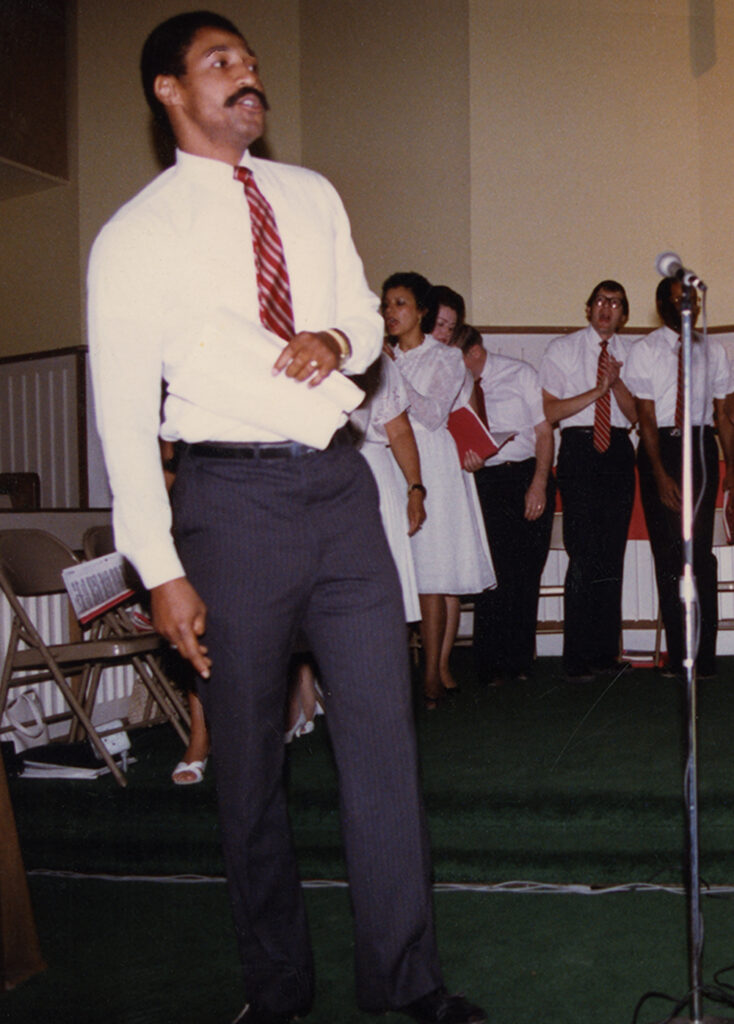

Green’s father, the Rev. Dr. Gerard Green Jr., was 17 at the time and remembers the white pastor who facilitated the gathering leading the prayer with tears streaming down his cheeks. “And in that moment,” Rev. Green says in the film, “I realized Dr. King’s death wasn’t about Black folk or white folk. It was about relationships between human beings.”

It’s one of many poignant scenes in the documentary, which has threads both universal and deeply personal for Jason Green. “At its core, it’s a film,” says Wayne Fields, the Lynn Cooper Harvey Distinguished Chair Emeritus in English in Arts & Sciences, “anchored in honoring his family.” Fields served as teacher and mentor to Green as a student and continued to maintain close ties through his White House years and up to the present. With the idea of the documentary still germinating, Green visited Fields at his Iowa home to workshop a script and talk through its themes.

“Jason wasn’t just somebody who found a good subject and did the research and produced a film,” Fields says. “He was so deeply involved, and so concerned that his family understand his respect and love for them. It made the film a more profound experience in the end.”

After that fateful night in April 1968, the three congregations eventually merged into one and became known as the Fairhaven United Methodist Church. The community known as Quince Orchard, however, became a victim of suburban sprawl, remembered mostly by the name of a road that remains and a high school incorporated in the late 1980s.

The story about the fight to keep the name “Quince Orchard” alive in the naming of the school is yet another facet to this tale — and another reason why this documentary came to be. In the wake of his White House experience, Green was invited to share his story with students at Quince Orchard High School. When the students, who had never known the origin of their school’s name, expressed interest in helping him discover more about the history of the community, he says he told them of his plan to write a book. “Do you guys want to help?” he asked them.

“And they said, ‘Absolutely not.’

“They asked, ‘What about a film?’ And I said, ‘Sure,’ thinking they’d forget about it over the summer,” he says. They didn’t. “By the time the fall semester came around, they had recruited some 50 students to be part of a club that was committed to uncovering and preserving community stories through history.”

The past, the present and the future had converged to uncover the history of a dirt road in rural Maryland — by way of WashU.

A WashU story

Green’s story as an Ervin Scholar and a political science major in Arts & Sciences, who also studied finance, has been well-documented at WashU. But how he found his way to the university is a good story, too.

As a young high school student in Gaithersburg, he remembers going to a college fair unprepared and overwhelmed. “But I was smart enough to know who would be prepared,” Green says. So he followed those three or four folks around the college fair; every booth they visited, Green was just steps behind. And one of them was WashU, to which Green happily turned over his home address for swag.

Admissions did its thing, so by the time Green was applying for college, WashU was a household name. His acceptance as an Ervin Scholar prompted him and his parents to make the visit — even though his mom was still insisting on the “east of the Mississippi” rule. What made the difference for him and his family: meeting a man named Jim McLeod, who served as vice chancellor for students and dean of the College of Arts & Sciences.

What McLeod did for Green while he was a student was life-changing. “He was that person who could lift your head up a little bit,” Green says of McLeod. “So you were always setting your sights higher than you’d set them yourself.”

But it was the community that the late-McLeod had created at WashU for generations of students — even decades before Green matriculated here — that also played a role in the creation of Finding Fellowship. It was McLeod, Fields says, who had championed a community on campus that had many of the same characteristics of a church community — one of care and concern for one another, and the idea that if an individual succeeds, all succeed. McLeod’s mantra, knowing students “by name and by story,” is immortalized on a walkway, which bears his name, into the South 40.

“Jim McLeod never talked much about his own origin story, but he, too, was the son of a pastor at a church in Alabama not far from where the Birmingham bombings took place,” says Fields, who became close friends with McLeod after years of working together. “He would talk about his family, but he never went back and revisited that turmoil of growing up Black in the South in the 1960s. Instead, he put all his energy into creating a community on campus much like a congregation, where you know everyone and you look out for each other.”

McLeod’s influence was very much part of the WashU experience when Green arrived in the fall of 1999, not knowing a single person, but jumping into a contained environment that felt somewhat familiar. And one in which Green ultimately thrived.

“Jason had already been brought up in that tradition in which you take care of one another, a product of churches and schools in a community served over and over again by the family unit,” Fields says. “That’s representative for all of us, as a kind of model for how things come together. I think, in some small part, this documentary could also be a tribute to Jim McLeod and the story he was trying to draw out of all of us, so that we know one another better.”

A universal story

There’s that word story again. What Green has done with Finding Fellowship is take a story that is so deeply personal for him and turn it into one to which we all can relate — and need during our current times. “Ours is a legacy of the possible,” Rev. Green says to the Fairhaven United Methodist congregation in 2018 at the church’s 50th anniversary celebration depicted near the end of the film.

“Storytelling takes time. It takes proximity. It takes place,” says Jason Green, who, for now, is maintaining close ties to his Maryland community. In addition to being a co-founder and senior vice president of a firm called SkillSmart, a technology company working to ensure infrastructure development is equitable and inclusive, he is also leading an effort to raise money for the Pleasant View Historic Site, the only church that remains of the original three churches. That has also led him to join and chair a commission in Montgomery County, Maryland, focusing on the region’s history with racial terror lynchings and promoting greater community understanding to lead toward reconciliation.

“Storytelling takes time. It takes proximity. It takes place.”

Jason Green

Green is essentially collecting more stories. “We don’t have time or proximity or place anymore,” he says. “Generations aren’t living close enough to one another where we can sit at the knees of our ancestors and hear their stories. And when I talk about time, these stories take multiple tellings to resonate. We don’t have the capacity to hear the stories from the elders over Sunday dinner anymore.”

So Green is doing his best to use the methods available now, in 2022, to impart a message. The film ends with a simple placard that reads, “The cost of liberty is constant vigilance/The cost of community is the same.” A charge to keep going?

“It would be a shame to have gone through all of this and learn the skills and not tell more stories,” Green says. “I’m really moved by this idea of place-based reconciliation. So we’re working on the early stages of a project where we can source more stories that highlight the storytelling ability of ordinary people.

“You know, in 1967 Martin Luther King wrote a really prophetic book asking, ‘Where Do We Go From Here? Chaos or Community?’ And I think we’ve seen a lot of examples of the chaotic — so many years of mayhem. We haven’t necessarily put forward enough examples of the community. But they’re out there. And now it’s our responsibility to lift up these community-based stories because they help remind us of who we are and what we are capable of.”