Manchild in Wonderland

“Think about it, Gerald. In the 1950s, you saw the rise of the dark-skinned Black man in American popular culture: Jackie Robinson, Miles Davis, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Sidney Poitier. That ought to tell you something.”

—A conversation I had with the late Stanley Crouch

In 1960, when I was 8, my mother took me and my sisters to see a Sidney Poitier film called All the Young Men, a Korean War drama. (The Korean War was the first war we fought with an officially desegregated military thanks to President Truman’s 1948 executive order, an important fact to know to understand this film.) As I was watching it, I had no idea that this was the same actor [Sidney Poitier] I saw in Porgy and Bess [a year prior]. Naturally, this film, about conflict, combat heroism, chivalry, patriotism and leadership, was more appealing to me as a boy than it was to my sisters and obviously more appealing than Porgy and Bess, which I did not even understand. Unlike Porgy and Bess, Poitier was the only Black actor in All the Young Men, and this was to be the template for the heyday of his film career, a Black person mostly surrounded by whites.

(This formula worked well for him — he won his Academy Award for Lilies of the Field, where he played a handyman who helps a group of German nuns build a chapel — until the late 1960s when Black Power and anti-integrationist aesthetics dominated Black thinking, and this sort of hero was no longer acceptable. Black performers like Sammy Davis Jr., Jimi Hendrix, Poitier, Johnny Mathis, the Supremes of Motown — all integrationist inspired — adjusted to this profound shift, but it cannot be said that there were no adverse effects for them or that they were made truly “authentic” by the change. Authenticity was the thing, as the existentialists used to say, and for Blacks by the late 1960s, the turn was from what is now called respectability politics to the cult of criminality — the criminal as hero and artist; crime as creative resistance. The late Stanley Crouch [culture critic, novelist and columnist] told me that the Black bourgeoisie and Black intellectuals had become infected with what he called “the Romanticizing Macheath Syndrome.” [Macheath is the chivalrous highwayman who commits crime but abhors violence from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.])

In All the Young Men, Poitier was a tough Marine sergeant who was placed in charge of a small company by the dying white lieutenant, over a more experienced white sergeant played by Alan Ladd. (Ladd had been a major star in the 1940s and 1950s, starring in Shane, considered by many one of the finest westerns ever made. By 1960, his day was done. It was a sign of how each actor’s fortunes were tending that they were given equal billing. Poitier’s star was definitely rising.) One member of the company (played by Paul Richards) is an outright racist who sows seeds of doubt about Poitier’s character’s ability. It is, in its way, a film that anticipates the drama over affirmative action. Poitier, as it turns out, is better than any man in his company, smarter, braver, tougher.

I loved the movie. I absolutely adored Poitier’s character. I went back by myself to see the movie again.

“I now knew who Sidney Poitier was, and I would, for years after, see any movie he was in.”

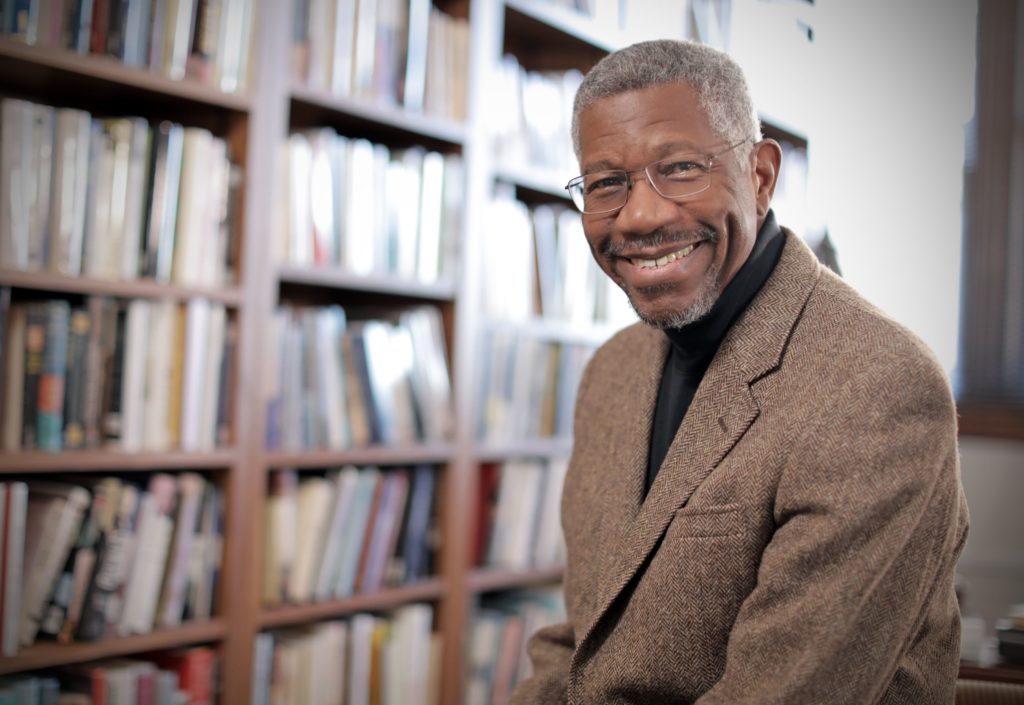

Prof. Gerald Early

I wanted to walk like Poitier, talk like Poitier, act strong and dignified like Poitier. Because he was from the Bahamas, although born in America, and my mother’s father was a Bahamian, I felt an even deeper connection to him.

All the Young Men became my equivalent of Burt Lancaster’s The Flame and the Arrow, the Black boy’s fantasy movie about an impossibly heroic person, an impossibly competent person, who fights for king and country. Poitier’s character made me proud to be an American, made me feel as if I was an American without any hesitation or crippling doubt. The movie had more “swashbuckling” than a Black hero had ever done before. The only thing that was missing was that Poitier did not get the girl. He could have been given a girl. I knew white heroes in war movies got the girl even in the most contrived ways. But Poitier was still everything for me. In the years that followed, for most of the decade of the 1960s, whether I liked or disliked his movies, Poitier was this one thing for me: The Flame and the Arrow in American films.