When you think about creative professions, painter and designer might come to mind, while engineer and network analyst might not. But creativity is actually inherent in nearly every type of problem solving.

“The creative process at its best seeks solutions to problems that improve the condition of the world and ourselves,” says Bruce E. Lindsey, the E. Desmond Lee Professor for Community Collaboration in the School of Architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

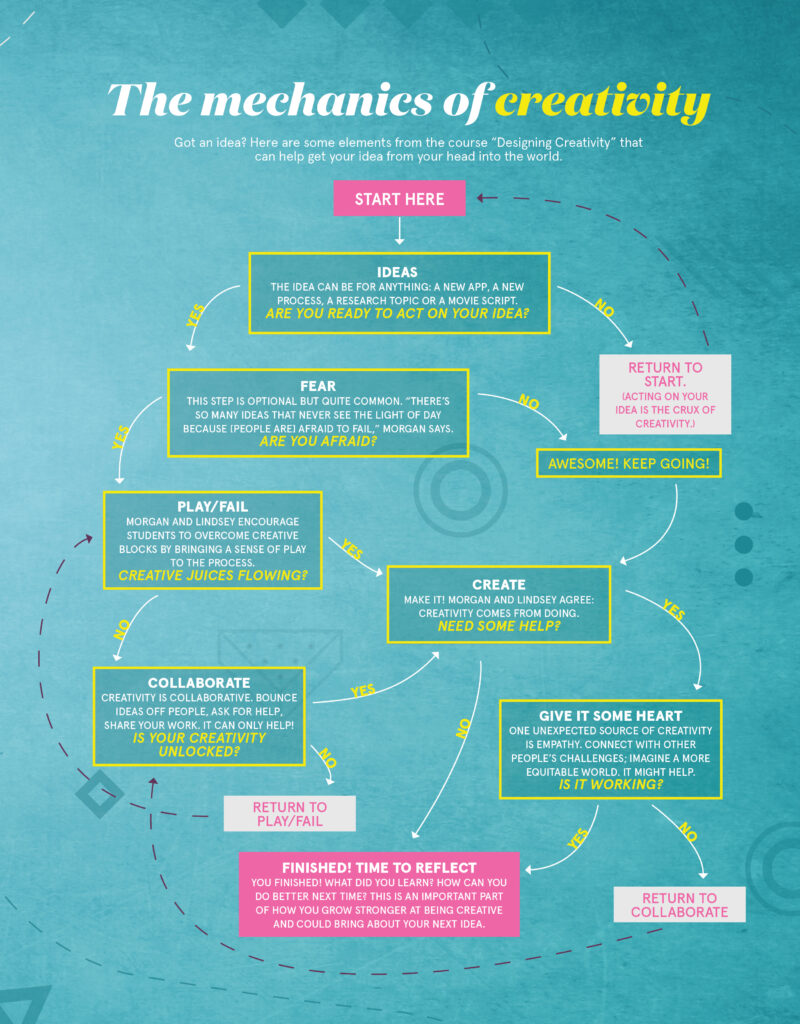

Lindsey co-teaches the course “Designing Creativity: Innovation Across Disciplines” with Robert Mark Morgan, teaching professor of drama and director of the Beyond Boundaries Program. Morgan and Lindsey launched “Designing Creativity” in 2015.

How do Morgan and Lindsey teach creativity? Well, they don’t exactly. They provide students with the tools to understand the creative process better. One way they do that is by bringing in guest speakers, such as actors, comedians and writers, as well as anthropologists, real-estate developers, chefs, athletes and chancellors.

The class also emphasizes the importance of acting on your ideas. “You’re more apt to act yourself into thinking than think yourself into action,” Lindsey says.

Course projects change each year, but in the past students have designed stools out of cardboard; made an instrument and then written a 30-second jingle with it; created a device to protect an egg when dropped two stories; and built Rube Goldberg machines, complex machines that do a simple function, which they call WUbe Goldberg machines.

Almost all projects are done collaboratively. “Collaboration allows you to be creative in ways that you can’t be by yourself,” Lindsey says.

Collaboration is actually a course unit. And since the course is open to all first-year undergraduate students, regardless of school, it is a chance to hear really different perspectives.

“That diversity is one of the course’s greatest strengths,” Morgan says. “I’ve had students in their fourth year say, ‘Your class was one of the only ones I took that involved students from other divisions.’”

Lindsey and Morgan also teach a course unit called Play/Fail. It’s designed to get students comfortable with the idea of failing and with generating creativity through play.

“Failure is inherent in every aspect of life,” Morgan says, and it’s part of the creative process. Morgan’s favorite photographer, Norman Seef, wrote about his creative process. “His second of seven steps is fear and resistance,” Morgan says.

But as kids, it was different. To highlight this, Morgan asks students to draw their neighbor in class in one minute and then exchange portraits.

“More often than not, when they share that sketch, they apologize,” Morgan says. “But the underlying theme of the exercise is the fact that when they were third graders, they didn’t apologize. They said, ‘Look at this!’ They had this courage as children to be creative and share their creativity with others.”

“Play really gets to the beginner’s mind,” Lindsey says. “We forget how rewarding playing is as a way of exploring ideas.”

Students — who are invited to come back as TAs after they finish the course — are also asked a new question about themselves. Instead of, “How intelligent are you?” (which is implied in traditional education’s constant testing), the course asks, “How are you intelligent?”

The question, Morgan says, “is really the crux of the class. What we want students to do is see themselves in a new light and understand what unique characteristics they bring forth.”