In the class “Innovating for Defense,” WashU students are putting their entrepreneurial skills to the test by solving problems for the U.S. Department of Defense. This classroom crucible, where students confront real-world scenarios, develops their leadership skills and, in the process, reveals the common threads underlying any high-level organizational challenge.

“Innovating for Defense,” or “I4D,” is co-taught by Peggy Matson, program director of graduate studies in Engineering Management and Project Management in the McKelvey School of Engineering, and Doug Villhard, professor of practice in entrepreneurship and academic director for entrepreneurship in the Olin Business School, and requires students to team up and address four pressing DoD projects. These students, primarily from the McKelvey School and Olin, benefit from the wealth of experience Matson and Villhard bring to class, even if working in the area of defense is new for both of them.

Matson’s expertise includes electrical engineering and software development, and she spent 30 years at Motorola leading technology strategy. “I come from that innovation space,” says Matson, who has four patents. Villhard, after working at Disney, has become a successful serial entrepreneur, starting, advising and investing in a variety of companies. “There are always opportunities to innovate and improve,” Villhard says. “That’s where I come in, because entrepreneurship is about looking for new ways to solve problems and to create a culture of solving problems.”

Complementing this dynamic teaching duo is Jake Laktas, part of the government-funded National Security Innovation Network (NSIN), which has launched similar courses across a select group of universities. Laktas is the liaison between WashU and the DoD, sourcing the projects and department sponsors and contributing to the course design.

So how exactly do entrepreneurship and defense intersect? “When people think of the Defense Department, sometimes they go right to bombs and missiles, warships and drones, all that stuff,” Villhard says. “But the truth is we don’t do anything that’s classified. It’s basically as if the Defense Department was a big company, and they have all kinds of inefficiencies, just like all large organizations.”

“It’s about putting down hypotheses, then going out to test them.”

Peggy Matson

The course is built around the lean startup methodology, an entrepreneurial model developed at Stanford. “It’s not about creating a big, fat proposal — which would be the traditional business plan — with a bunch of detailed financials you don’t know enough about and are investing all this time in,” Matson explains. “It’s about putting down hypotheses, then going out to test them.” Each week, I4D students engage in five or more interviews. “We encourage them, force them really, to go out and talk to people, ask open-ended questions, and look for the nuances to really get to the bottom of it,” Villhard says. “I think that’s a particularly nice takeaway for this next generation — the value of the interpersonal.”

From there, each team creates a prototype, changing and adapting their original hypotheses based on what they’ve learned. In I4D, first taught in Spring 2021, this has resulted in effective, often complex, innovations for the DoD; in entrepreneurship, this can reveal a startup’s ideal business model, well before major investments have taken place.

And just as the DoD projects are demanding, so are classroom expectations. As stated in the syllabus, students receive “relentlessly direct feedback” on their prototypes and presentations. “The course instruction yields an incredible balance of caring,” says Matson, “and at the same time, a laser focus. Our goal is that students find an opportunity that really sings.”

Up to the challenge

While I4D’s students, many of them adults already employed by companies such as Boeing, may not go on to found their own businesses, one thing is clear: To become successful leaders, they must first become high-level problem-solvers, whether it’s in the defense or civilian sector. Matson and Villhard are not only teaching about entrepreneurship (as well as the increasingly critical concept of intrapreneurship within an established company), they are teaching students how to enact an idea, preparing them for any organizational challenge to come.

In one of I4D’s challenges this past spring, WashU students addressed a flooding problem in a hangar at nearby Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. Villhard describes how, for many years, the hangar had flooded during severe storms, posing a risk of delay for critical missions and classified flights. Previous efforts and expenditures hadn’t fixed it, so five WashU students took a turn, addressing the issue from an engineering and financial standpoint.

“In talking to all these folks, there were three potential solutions … And the students put those together for the base commanders to make a decision.”

Doug Villhard

“In our process of helping them solve it,” says Villhard, “we were introducing people to each other on the base that hadn’t met before, hadn’t sat down in the room at the same time to consider this. Sometimes innovation projects at large companies come down to just saying ‘this is a priority, let’s put our best people together.’ In talking to all these folks, there were three potential solutions right under their nose: one pretty cheap (a berm/dirt barrier along with a deployable water barrier and flood sensors), one medium-priced (a reinforced concrete barrier plus deployable water barrier and flood sensors), and one high-priced (an underground water storage basin that holds water until it can be dissipated into a nearby creek). And the students put those together for the base commanders to make a decision.”

“They were very happy with the result,” Matson adds. “The solutions were top-notch.”

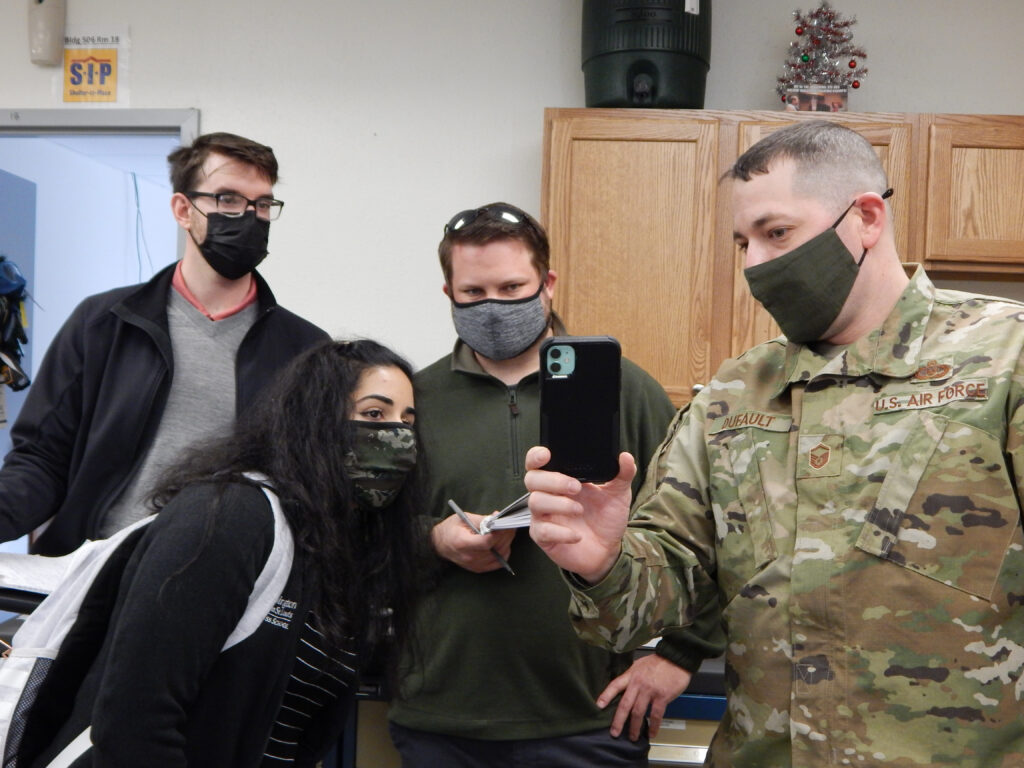

In another project for Scott Air Force Base, students focused on flight-simulator training software that wasn’t keeping up with the iterations of cockpit redesigns in planes. “Pilots are getting in and finding this button is now over here, or under here,” Matson says. “Our students were presented with the dilemma of how to get the appropriate training.” Yet during an interview with an Air Force official from another base, students discovered that the training gap had already been addressed at that location, so the problem then became how can the innovation scale be expanded so the issue was addressed across bases. “They totally reformulated the problem, so how that evolved was quite a thing,” Matson says.

During a project with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), students looked at fresh approaches to analyzing disparate data. “For example,” says Matson, “say an armored caravan was moving through a country like Iraq, and suddenly they see a crowd around them. How do you understand the difference between being attacked and accidentally going through a festival that’s going on at that time? How do you gauge hostility caused by driving through that?” By aggregating data from many applications and sources, even local news, weather and multimedia, into a central point that can yield intelligence, students helped make sense of such area-specific conundrums.

Ingenuity with vision

A central principle of the course is that the solutions students propose can also carry over into civilian use. “If we can create a solution that could sell in the DoD, and also sell in the commercial world, doesn’t that double the opportunity? So we teach that as a concept, and try to choose problems that open students up to a solution with potential dual use,” says Matson, who has lectured on entrepreneurship to different communities around the world. This “dual-use” concept emerged in the prototype for the NGA project, where students also envisioned its use with the St. Louis Police Department. “It could help in understanding what’s going on in certain neighborhoods at certain times and when those are good times for police presence, or maybe not. Just helping to understand the community a little bit better based on data,” Matson says. “That’s an example of doing something for the NGA, both as a defense purpose and a domestic purpose as well.”

“If we can create a solution that could sell in the DoD, and also sell in the commercial world, doesn’t that double the opportunity? So we teach that as a concept, and try to choose problems that open students up to a solution with potential dual use.”

Peggy Matson

Not only do students’ innovations reach beyond the project at hand, so do the lessons learned. Again and again, students found that the answers were always there, it was a matter of finding the right combination to unlock them. In the Scott Air Force Base flooding project, WashU students brought together groups who hadn’t talked before, focusing broader areas of expertise toward a specific goal. In the flight training scenario, a gap between training systems and actual flight systems was addressed, with implications for streamlining future technology implementation. And for the NGA, channeling multiple levels of data helped lead to new ways of understanding situations.

A common thread that emerged in these projects — that assembling the right team is key to overcoming organizational challenges — was a revelation precipitated by I4D’s class structure itself, where McKelvey School and Olin Business School students worked side by side. For both professors and students, this combination of engineering and business opened up new possibilities. “It’s interesting, even within WashU, how teaching a class can help us better collaborate,” Villhard says. “Olin Business School is now partnering with the School of Medicine for the class ‘Innovating for Health Care’ as well. We’re getting a problem set from BJC HealthCare, and medical students and MBA students are working together. So not only is this class good for our Defense Department collaboration, it’s been good for WashU too.” Matson and Villhard will teach I4D again in Spring 2022, and both are looking forward to the entrepreneurial discoveries that await.