On any given day, the Danforth Campus of Washington University in St. Louis campus offers an opportunity to revel in its rich poetry tradition, if you know where to look.

Places such as east of Olin Library, where an allée of ginkgo trees stands and that once inspired Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov to write “The Consent.”

Or in University Libraries’ Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, where you can find a blue book that displays the scribbles of a young T.S. Eliot.

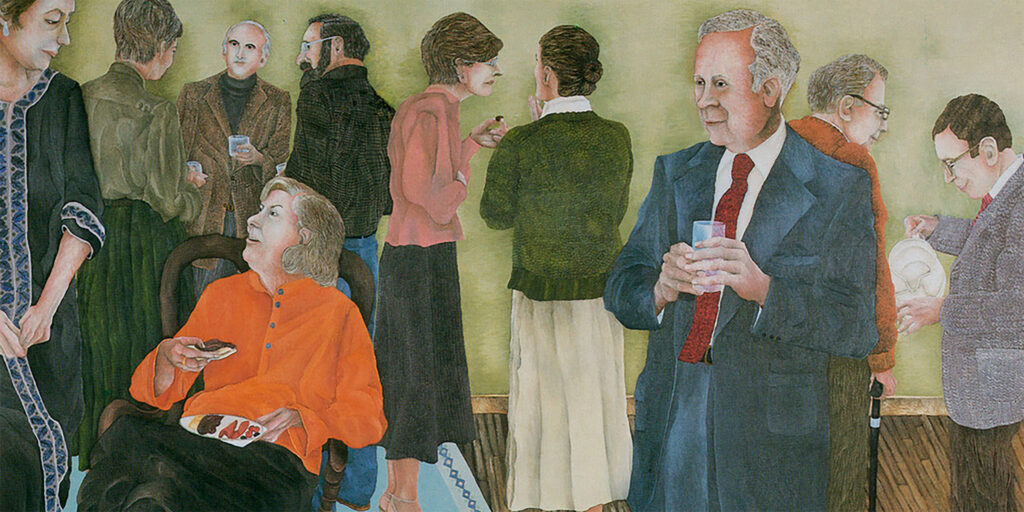

Or in a faculty meeting room of Duncker Hall, where a painting by Joan Elkin, called “Jarvis Thurston and His Circle,” features literary power couple Thurston and Mona Van Duyn, the first female U.S. poet laureate, holding court with Donald Finkel, Stanly Elkin and Richard Stang — a snapshot of late 20th-century literati.

The trees murmur. The walkways retain long-faded footprints. The halls echo sounds of literary giants past and present, all of which makes the Danforth Campus a rich place to study poetry.

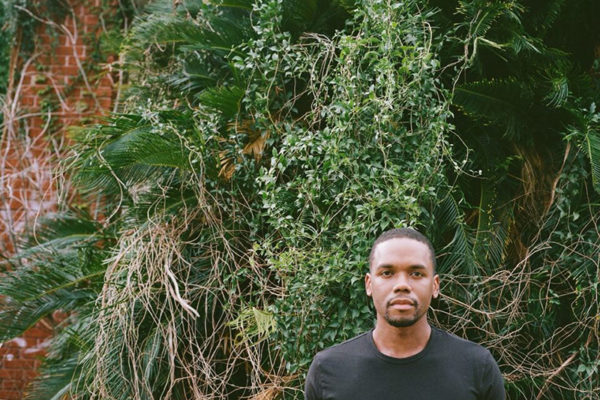

“People talk about poetry as being superfluous to life, but everybody has a quote or a song lyric that’s dear to them,” says Aaron Coleman, a 2015 graduate of the MFA program in poetry and a PhD candidate in comparative literature on the international writers track, both in Arts & Sciences.

“Poetry creates new spaces in language. New space for complex emotion, reflection and imagination,” says Coleman, who has published two books of poetry since earning his MFA: Threat Come Close (Four Way Books, 2018), winner of the Great Lakes Colleges Association’s New Writers Award, and St. Trigger (Button, 2016), winner of the Button Chapbook Prize.

Coleman is also a Fulbright Scholar and a Cave Canem Fellow who has had essays and poems appear everywhere from the New York Times Magazine to the Boston Review and Callaloo, among others.

And for the past seven years, he has called St. Louis his home as he’s been writing, studying and earning his doctorate under Ignacio Infante, associate professor of comparative literature. It’s a relationship fostered while Coleman was earning his MFA, and one prompting him to continue his graduate education at Washington University to study the poetry of language in translation.

“Poetry creates new spaces in language. New space for complex emotion, reflection and imagination.”

Aaron Coleman

“Poetry aims to express the intangible, and that’s perhaps why it’s hard for people to get a grasp on it,” Coleman said in March, just a few weeks before he turned in his dissertation. “Intangibility doesn’t undercut its value, but it is intimately valuable to help people understand their experiences, emotions and identities.”

For Coleman, that’s an identity as a poet and a Black man seeking to understand his heritage and racial disparities in this country. It’s an identity he has forged from his days as a college football player, when he put down his helmet after two seasons at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, and picked up words. “Poetry,” he says, “became my language to talk not just about American culture and football’s strange place in it, but to process my own life experiences.

“I realized I wasn’t being fed by football in the way I was being fed by poetry.”

That he later found himself at WashU studying poetry under acclaimed contemporary poets Carl Phillips and Mary Jo Bang, and alongside Justin Phillip Reed, a fellow 2015 MFA in poetry who would go on to win the National Book Award for Poetry in 2018, was fortunate for him and the university. It was a program he was attracted to, he says, for its “diversity of poets and approaches to poetry,” after finishing his undergraduate and spending time living and traveling overseas.

“I wanted to go to a place that was going to give me the time, space and resources to work with people who are masters of contemporary poetry,” he says. “I don’t think that’s an overstatement. Carl and Mary Jo are historical figures who continue to shape the possibilities of poetry today. As their student, I was overwhelmed with the way they were able to bring together their imagination and lived experience to create poems that didn’t look like anybody else’s poems.”

Mentoring from contemporary literary giants is just one of the reasons WashU’s MFA in writing has become nationally renown. It is now one of the university’s most selective graduate programs.

“The people I met in the program when I visited, and the people who were in my cohort, we weren’t the same [type of] writers at all, yet we all loved poetry,” Coleman says. “We’re all trying to carve out a new way to use language.”

And share those words, too. “In poetry, as with all writing, there’s this deeply individual, personal ‘me’ on the page, but I’m on that page because I want to speak to someone else,” Coleman says. “It’s always my hope that someone will read it and have value or perspective added to their life.

“Sharing poetry changes your experience of space and time,” Coleman says. “It slows things down.”

To celebrate poetry at WashU, four celebrated poets shared their work as only they can, in their own voice. In a series of videos presented below, Phillips reads “Dirt Being Dirt,” a poem which explores the idea of “refusing to change the self”; Coleman reads his poem, “American Football,” which captures the beauty and violence of the game. Bang recites “All Through the Night,” a poem originally published in the New Yorker and inspired by the Cyndi Lauper song of the same name. And Paul Tran, a 2019 graduate of the MFA program and Chancellor’s Graduate Fellow, reads “Copernicus.”

Tran, who is also a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford University, returns to campus this summer to teach “Autobiography & Poetry” in the Summer Writers’ Institute. “Teaching is my form of activism,” Tran says. “It’s how I dismantle received ideas and investments. It’s how to pay forward the gifts given to me — the gift to think critically, to speak boldly, to dare imagine something else.”

For Coleman, who will earn his PhD this semester and then begin a postdoctoral fellowship in critical translation studies at the University of Michigan next fall, he’ll always be grateful for his time at WashU, in both the writing and comparative literature programs.

And for the poet, where place can be transformative, he recalls a particular space on the Danforth Campus: Hurst Lounge in Duncker Hall — that venerable building on the northwest corner of Brookings Quadrangle where legends have taught, learned and shared.

“That building has been there more than a century,” Coleman says, smiling as he recalls Thursday night readings with Reed and his MFA cohort. “So many different writers, of different styles, of different gravities, have all shared that space. I feel echoes of those moments whenever I’m inside that room.

“I’ll always walk through that door with gratitude for how I grew in there.”