As a teenager growing up in rural Massachusetts, Carl Phillips would wander trails with his dog. “The house [was] surrounded by cranberry bogs, and I spent a lot of time observing the changes in the landscape, the two swans that lived on one of the bogs, that sort of thing,” Phillips says. From this experience, he crafted his first poems.

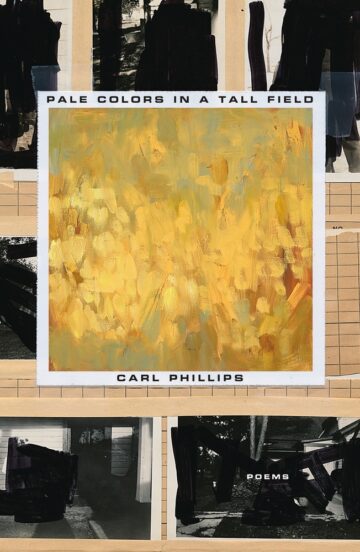

Throughout his career as a poet, which now stretches across 14 books, Phillips, professor of English in Arts & Sciences, has intertwined nature — wind, clouds, bees, foxes, horses — with ruminations on love, vulnerability, doubt, regret, desire. His latest collection, Pale Colors in a Tall Field, relies on those same powers of observation he sharpened years ago and brings in a touch of “linguistic sorcery” (according to one review) that Phillips has become known for. His complex syntax leads readers to experience the regret, the doubt, the longing that Phillips writes about.

“On Being Asked to Be More Specific When It Comes to Longing” is the second poem in Phillips’ collection. It begins in the midst of a walk and ends “with people lying down naked in a field as these creatures approach them,” Phillips says. “This is echoed in the poem that ends the book, where two people, despite not believing in rituals, take each other’s hand and make a kind of union as a way to move forward into — what? Who can say? But a move toward the unknown is a move toward change, toward disaster maybe, but maybe toward the next great adventure.

“I’m all about risk as a form of evolution. Otherwise, what’s the point of our time here

on Earth?”

On Being Asked to Be

More Specific When

It Comes to Longing

When the forest ended, so did the starflowers and wild

ginger that for so long had kept us

company, the clearing opened before us, a vast

meadow of silverrod, each stem briefly an

angled argument against despair, then only weeds by

a better name again, as incidental as

the backdrop the ocean made just

beyond the meadow … Like taking

a horsewhip to a swarm of bees, that they might

more easily disperse, we’d at last reached the point

in twilight where twilight seems most

a bowl designed to turn routinely but

as if by accident half roughly

over: bells somewhere, the kind

of bells that, before being housed finally

in their towers, used to

have to be baptized, each was given—

to swing by or fall hushed inside of,

accordingly—its own name; bells, and then—

from the smudged edge of all that

seemed to be left of what we’d called

belief, once, bodies, not of hunting-birds, what we’d

thought at first, but human bodies in flight,

in flight and lit from within as if

by ruin, or triumph, maybe, at having

made out of ruin a light, something

useful by which, having skimmed the water, to search

the meadow now, for ourselves inside it where, yes, though we

shook in our nakedness, we lay

naked as we’d been taught to do: when afraid,

what is faith, but to make a gift of yourself—give; and you shall receive.