Few are happy with how the COVID-19 pandemic was handled in the United States in its first year: staggering infection rates, hospitals running out of beds, a death toll that topped 500,000 (as of March 1, 2021). Restaurants and small businesses closed, opened and closed again, with many going out of business; unemployment numbers climbed; and in the midst of it all, misleading and conflicting information was both rampant and worrying.

So what went wrong?

“There’s a saying that when politics and science collide, too often politics win,” says Ross Brownson, the Steven H. and Susan U. Lipstein Distinguished Professor at the Brown School and medical school.

And did they ever collide with COVID-19. Simply writing about the response feels like traipsing across a minefield because how people view what happened depends largely on their politics.

“There’s a saying that when politics and science collide, too often politics win.”

Ross Brownson

While Brownson is interested in what politicians got wrong, he has also looked at what public health experts could have done differently. Even before COVID-19, there were fault lines in the public health field that the pandemic cracked wide open.

“For decades now, but especially since the recession in 2008–09, we’ve been dramatically underinvesting in public health,” says Brownson, who co-authored the article “Reimagining Public Health in the Aftermath of a Pandemic” for the American Journal of Public Health in late 2020. Most health-care dollars go to treatment, rather than to public health and prevention. Between 2008 and 2017, local health departments in the United States jettisoned 50,000 jobs, Brown says.

Another issue was political, particularly the lack of a national plan for action. “Early in the pandemic, the White House said, ‘We’re going to war with this virus,’” Brownson says. “Imagine if we were going to war, but instead of having a national response, we’re going to let each city in the United States and the 3,000 local health departments decide how they want to fight this war themselves.”

“There’s been a lot of talk about people wanting to return to normal. We ought to be thinking about not returning to normal but finding a new, more just normal.”

Ross Brownson

Graham Colditz, deputy director of WashU’s Institute of Public Health and a co-author of the article, says it was a “cacophony of messages and counter-messages.” As a result, “people don’t trust any of it,” says Colditz, who is also the Niess-Gain Professor of Surgery and division chief of public health sciences in the School of Medicine. This fueled the “infodemic,” the spread of misinformation about the pandemic on social media.

Public health officials also struggled to assess the impact of the virus, especially early on in the pandemic when it was difficult to get tested. Contact tracing, a main method for controlling the spread of the virus in South Korea, for example, was never truly possible for already overburdened local health departments.

In addition to revealing all the fault lines in public health, the pandemic also brought American inequities into sharp focus.

“We have multiple pandemics going on,” Brownson says. “COVID-19 is one, climate change is another, racial inequity is still another.” Racial inequity has been particularly striking during COVID-19 not only due to protests over the police killing of George Floyd and others, but also due to statistics like Blacks dying at nearly three times the rate of whites from COVID-19.

“There’s been a lot of talk about people wanting to return to normal. We ought to be thinking about not returning to normal but finding a new, more just normal,” Brownson says. “The old normal wasn’t so great for a lot of segments of society.”

The future of public health

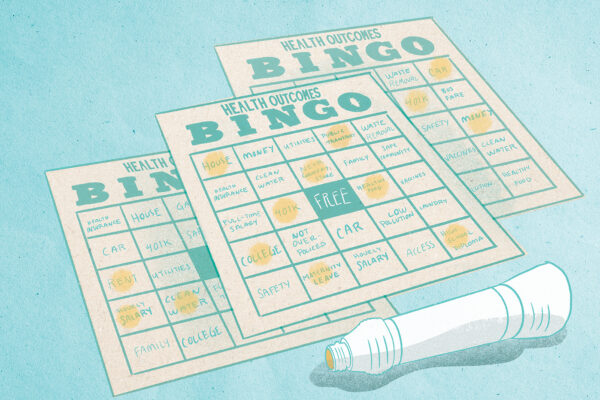

According to Brownson and Colditz, before the COVID-19 pandemic, public health was entering “version 3.0,” with a focus on the social determinants of health. When studying why people are dying or getting sick, public health experts ask certain questions to determine interventions: Did the person who died of lung disease smoke? Did this person die of heart disease because she didn’t eat a healthy diet? If the answers are yes, then resulting public health intervention questions might be: How can we get people to stop smoking? How can we create the environments to allow people to eat healthier?

“But those [questions] don’t get to the underlying social determinants of health,” Brownson says. “Maybe someone doesn’t eat a healthy diet because they live in a food desert or they can’t afford to buy healthy food. Maybe they smoke because they’re being bombarded by messages about smoking and not getting preventive messages.”

Expanding the view of what impacts health outcomes forces public health officials to consider how things like environmental, social and economic factors are connected to health risks. In order to study these systems, it is imperative for public health to garner more funding. Reprogramming even a small percentage of the health-care dollars that now go toward treatment to prevention could have a huge impact.

“Public health, when it’s working at its best, is invisible, because we’re incrementally preventing disease and improving quality of life,” Brownson says. But it saves millions of lives. For instance, safe drinking water and clean air prevent millions of Americans from getting sick and dying every year. But a physician removing a tumor is more visibly saving a life.

In addition to funding, Brownson advocates for a new generation of policy and practice leaders who have different skill sets.

“Public health, when it’s working at its best, is invisible, because we’re incrementally preventing disease and improving quality of life.”

Ross Brownson

“A big area involves communication skills,” Brownson says. Public health officials could learn a lot about getting out their message from marketers, advertisers and businesses. But they also need to learn how to combat disinformation online.

Colditz agrees. “We can do a much better job of connecting with different sectors of our society, different levels of health literacy and scientific understanding, so that everyone can get the benefit of what we know. All these excess deaths from COVID-19 aren’t because we didn’t know what to do.”

In the American Journal of Public Health article, Brownson also says public health leaders need to better plan how to study and intervene with social determinants of health. This might require increased use of big data and closer connection to sectors such as education, housing and employment.

“How do we go forward with more urgency and more equity as we chart the future? I think that’s the bottom line for me,” Brownson says.