Gerald Early, the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters, is a big baseball fan and sports scholar. He was in Ken Burns’ documentary Baseball, which came out in 1994. Plus, he writes extensively about the sport. Several years ago, he wrote an article where he took issue with Barry Bonds’ statistics being marked with an asterisk. (Barry Bonds took performance-enhancing drugs later in his career, but also has record-setting stats including hitting 762 home runs and 1,996 RBIs.)

Early said that if baseball was handing out asterisks, all of the records set when the major league was segregated should also be marked.

“Putting an asterisk beside Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak? Putting an asterisk by Ted Williams hitting .406 in 1941? You can’t do that!”

Gerald Early

“The outrage was just amazing,” Early says about the reaction to his article. “Putting an asterisk beside [New York Yankee] Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak? Putting an asterisk by [Boston Red Sox] Ted Williams hitting .406 in 1941? You can’t do that!”

At the time, Negro League statistics were not part of the official record of baseball statistics, so Black players — until the game was integrated — were entirely absent. Early was advocating for the asterisk not just because the game itself was segregated, but to let the public know that the records they were reading were all-white.

That changed in December 2020 when Major League Baseball announced that it was going to integrate its records and include seven Negro Leagues in the MLB stats.

The Negro Leagues were created in response to segregation. Major League Baseball did not allow non-white players before 1947. The first professional Black baseball team started in 1885 in Cuba; however, the Negro Leagues that will be part of the official records ran from 1920 to 1948 and represent some 2,400 players.

Why weren’t the Negro Leagues already included?

There are two reasons, Early explains. One is that the Negro Leagues didn’t operate as a league as we understand it today. Negro League teams did not play all of their games against each other. Instead, the Negro Leagues relied heavily on barnstorming games — or match-ups against any team that wanted to play them.

“They tried to emulate [Major League Baseball’s] structure, but it takes a lot of capital to do that,” Early says, “which those teams did not have.”

The other issue was the records. “Negro League owners did hire a statistical service to help keep records and statistics,” Early says. “But, of course, this was very difficult to do when you’re playing all these barnstorming games, because there weren’t records of that.”

Fans and statisticians at websites like seamheads.com have compiled more complete stats, and the organizational difficulties must be understood in context.

“The treatment of the Negro Leagues as something less than the major leagues was still kind of Jim Crow-ism,” Early says. Elevating the stats to major league status “rewards the owners of the Negro Leagues because it’s now saying that they were operating a league, [even] considering the constraints they were under, that was just as organized and as highly competitive as Major League Baseball.

“And it acknowledges that those players were just as skilled, and what they did on the field was just as important and just as significant.”

Some reports about the change talk about “ramifications” on the sport’s “cherished” record book. This reinforces the idea that the Negro League records are interlopers.

“There are a lot of traditional-minded people,” Early says. “And they might feel as though this is just a political move, so they might not like it. But on the whole, it will be fine. And probably for younger people coming up, they’d actually prefer this and are glad it happened.”

Remembering heroes

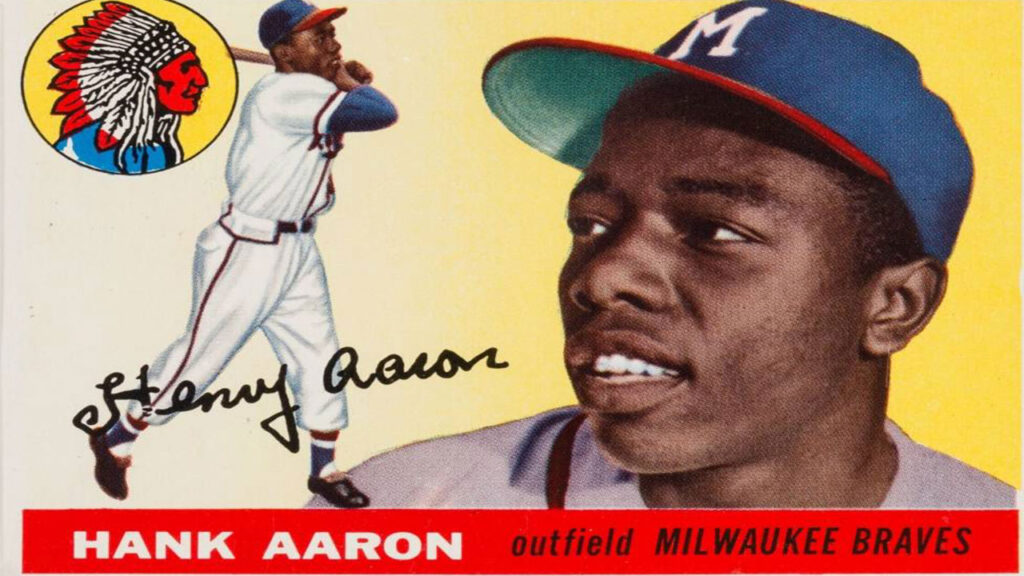

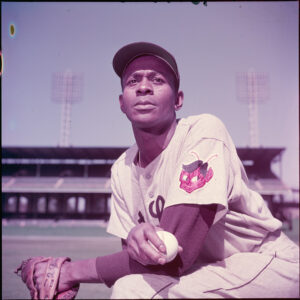

Early says it could even inspire more interest in the Negro Leagues. Early himself admires the dedication of those Negro League players, who played under often difficult circumstances. When blacks integrated the major league, they also had to show great determination. Early grew up watching Hank Aaron, when he played on the integrated Milwaukee Braves in the ’50s and ’60s. But Aaron got his start in the Negro Leagues.

“I admire all baseball players because I love the game,” Early says. “But my first Black heroes were the guys who played baseball and the guys who boxed. They were so good at what they were doing and so dedicated to it. And I would say to myself, ‘Oh, when I grow up, I want to be this good at whatever it is I’m going to do in life. And I want to be this dedicated to it.’”

Rosalind Early, AB ’03, is the features editor for Washington magazine and Gerald Early’s daughter.