It all happened so fast.

In late January, the university’s International Travel Oversight Committee, which had been closely tracking the new coronavirus in Wuhan, urged Chancellor Andrew Martin to bring students back from China before their semester began. He agreed swiftly — and then warnings flared for other parts of Asia, then Italy, then the rest of Europe and South America. University staff members worked with the U.S. State Department, negotiating border lockdowns and sending late-night emails to diplomatic officials to rescue a postdoc and an undergraduate who were trapped in Peru.

Almost 500 students had been safely brought back from 35 countries by the beginning of March. No cases of COVID-19 had yet been reported in Missouri, but as students left for spring break, “we sent messages saying, ‘Hey, this is rapidly evolving, so you might want to prepare for the possibility that you might not be able to return to St. Louis after spring break,’” recalls Rob Wild, interim vice chancellor for student affairs. “But hardly anyone prepared for that possibility.”

And then, in the middle of students’ beach trips and family time, the virus exploded.

On March 11, Martin extended spring break for an extra week, asked faculty to move their classes online and decided students would not return to campus for the rest of the spring semester. By then, St. Louis County had reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19, yet the city had reported none.

On the morning of March 16, Martin decided that all campus offices, labs and facilities — even the library — would close by March 23, and faculty and staff would work from home. He was acting, he hoped, in an excess of caution. That afternoon, he drove to the Medical Campus for a meeting he always looked forward to. The med school’s Executive Faculty got along easily, and before their monthly meeting, there was usually a good bit of teasing and chitchat.

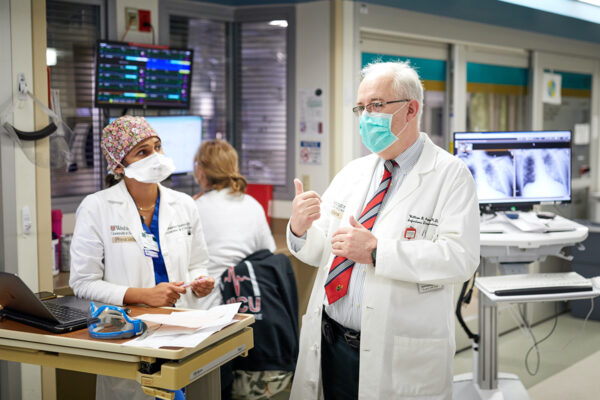

But the only sound that day was the scuffling of chairs. Airless and taut, the atmosphere reminded Martin of a war room, with generals preparing to send their troops into battle. Dean David Perlmutter, MD, listed off the challenges of canceling elective surgeries, accessing PPE for frontline health-care workers, obtaining testing for COVID-19 and partnering with BJC HealthCare to staff the hospitals. Since early January, a team had been meeting at Barnes-Jewish Hospital to plan for a possible outbreak. Most office and clinic visits would be converted to telemedicine, and researchers would tackle COVID-19 from every angle, pausing most other research in more than 600 laboratories.

“We are closing now. … We can meet on Zoom. I don’t know when I’ll see you all in person again, but I hope it’s soon.”

Chancellor Andrew D. Martin

Until that meeting, Martin had been acting with calm urgency. Now, as he watched the grim faces of the med school physician leaders, dread iced his heart. He returned to his office at Brookings Hall and gathered his staff. “We are closing now. I’ll have a phone line installed in my home office. We can meet on Zoom. I don’t know when I’ll see you all in person again, but I hope it’s soon.”

This pandemic was about to challenge education, research, patient care — every aspect of the university’s mission. It would toss the very definition of a university in midair. And then, Martin quickly reminded himself, the Washington University community would catch that definition, make whatever adjustments were necessary and move forward.

When you gather some of the brightest minds on the planet and give them a framework in which to collaborate, you don’t have paralysis or chaos. You have diversity, intelligence, creativity and compassion.

The strengths of this university were exactly what would save it.

Painful necessities

When students scattered for spring break, many went, unwittingly, to areas where the virus was about to take off. If they had returned to campus for even a weekend, they could have endangered one another, not to mention staff, faculty and the rest of the St. Louis community.

“And we regret that the circumstances are requiring us to take such an unusual course of action. We’re doing what we believe is absolutely necessary to protect our community.”

Chancellor Andrew D. Martin

“We know these are major decisions,” Martin said in a message to the university community. “And we regret that the circumstances are requiring us to take such an unusual course of action. We’re doing what we believe is absolutely necessary to protect our community. We can’t predict how any of this will turn out … but based on what we know now and where we think this could be headed, we think that we must err on the side of caution and do all we can to reduce our risk.”

So began Operation Pack and Ship. The week of March 16, almost 200 faculty and staff members volunteered to carefully retrieve the essentials specified by 4,000 students — my laptop, my books, my violin, the red notebook in my top drawer — and to add a warm note of encouragement to the box. Music professors supervised the delicate packing of instruments, says Kawanna Leggett, interim associate vice chancellor and dean of students. Her staff rescued and tended the students’ beloved houseplants, fish, a few contraband frogs and snakes, and an illegal gerbil. The Burning Kumquat organic garden was harvested by Trevor Sangrey, assistant dean of Arts & Sciences; Anika Walke, associate professor of history and Sangrey’s partner; and their son. They froze, donated and replanted for the students’ fall harvest. And they even made garlic scape pesto to surprise them.

Once Martin had made the decisions to empty the dorms and close the campuses, a peace had settled. There was Herculean work to do — setting up websites, figuring out refunds, sanitizing buildings, helping faculty pivot to online — but now, instead of agonizing over pros and cons and hypotheticals, he felt only a profound sadness. Few local institutions had done anything this drastic. But it was the only surefire way to protect the WashU community and — given the size of the university’s workforce — help slow the spread of the virus in St. Louis.

On March 20, St. Louis County reported its first COVID-19 death. By March 23, there were deaths in St. Louis City and St. Charles County.

Once the shock of shutting down set in, Martin was barraged with questions: When could students get their stuff back? When could faculty have access to the library again for their research? He was making one hard decision after another, rarely with enough data for comfort.

Late at night, his worries started big — the disease seeping across the world map, the future of the university — then zoomed in tight and personal: his daughter, Olive, bereft because they had canceled their epic father-daughter spring-break trip to the Smoky Mountains; Asian students maliciously attacked by St. Louisans screaming at them to “Go home”; health-care professionals about to risk their own health and that of their partners and children; members of the WashU community saying his precautions were too hasty, sacrificed too much.

The criticism, he shook off. This virus could spread with a cough or a song — and it could kill. Washington University’s response must be rigorous, he thought resolutely.

But oh how Martin dreaded canceling Commencement.

“Please bear with me as I try to get through this extremely difficult message,” he asked the Class of 2020 by video. He kept thinking back to his own senior year. “I understand that this must feel like an even bigger dagger to the heart at a time when you already feel knocked down.” They’d lost the last six weeks, missed their last lab experiment, recital, tournament, play, debate — not to mention Thurtene and all the senior class rituals, parties and goodbye hugs.

But their safety had to come first.

Staying connected

With the closure of campuses, adrenaline surged. “One of the chancellor’s first messages when he arrived was, ‘Respect your staff. Don’t send them emails in the evening or on weekends; wait until Monday morning,’” recalls Michael Wysession, professor of earth and planetary sciences and executive director of the Center for Technology and Learning. “For those of us working to make the shift to online teaching, that had to go out the window!” Wysession also heads the IT Teaching and Learning Committee, and phone conversations were taking place as late as 3 a.m.

Chris Kielt, vice chancellor for information technology and chief information officer, swiftly assembled a huge team of IT leaders from across the university: “Every week we had people from McKelvey, Olin, Brown, Arts & Sciences, the med school, the Center for Teaching and Learning …” — all working together to do what a few months earlier would have seemed impossible.

Luckily, the university had switched its online-learning system to Canvas the previous fall, Wysession says, “and we’d already looked at some other pieces of software we didn’t think we’d need much — you know, like Zoom.”

In April alone, WashU logged more than 590,000 Zoom meeting hours.

“Literally everyone on campus was suddenly working from home,” Kielt says. “We were figuring out how to deliver equipment safely and how local internet bandwidth problems could be alleviated.” The digital divide was now sharply obvious: About a third of the undergraduates had been sharing a roommate’s laptop or couldn’t connect from home. IT launched a telecommuting page and a Zoom portal, and everyone in IT took a stint on the phone line helping to respond to requests for assistance via an online ticketing system, making sure no one felt the urge to hurl their laptop through a window.

Meanwhile, Wysession’s committee was galvanized by “the thought of 1,000 faculty members teaching online, when most had never taught online and some were vehemently opposed to the philosophy of it.” In two days, they created a full website of resources. The teaching was what mattered; the form could be adapted.

Shared urgency

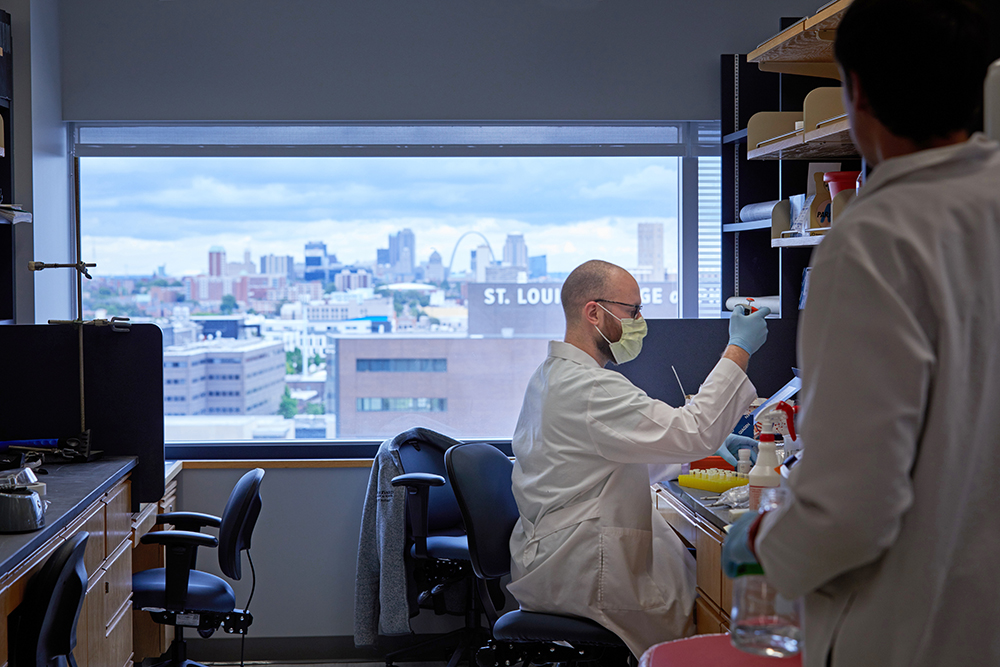

The med school had a head start on the coronavirus. Sean Whelan, MD, had moved to WashU from Harvard University at the end of 2019, settling in as the Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor and chair of molecular microbiology. He asked one of his new colleagues, Michael Diamond, MD, if he was thinking of working on the mysterious new virus that had emerged in Wuhan. Diamond, who is the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine and also holds appointments in pathology and immunology, said, “Yeah,” he’d been thinking about doing just that.

Whelan nodded. “Me, too.” They decided to meet once a week to compare notes.

By early March, those weekly meetings included researchers from more than 40 labs across campus. Whelan was building on past work with Ebola: He had used the genetics of a livestock virus, harmless to humans, to change its surface protein. If he could make a harmless virus look like the COVID-19 virus, maybe he could generate a protective immune response.

Diamond had done pioneering work on Zika, helping to develop a mouse model of the viral infection and identifying an antibody that’s now used as part of a diagnostic test. For the COVID-19 virus, he generated mouse models that would speed the search for treatments and vaccines. Using those models, he showed the therapeutic value of human antibodies produced by the immune system to fight COVID-19 and the possibility of making monoclonal antibodies in the lab. As the clinical trial of the monoclonal antibodies began, he developed a vaccine using a harmless chimp adenovirus that could be easily administered with a nose spray and had a robust immune response.

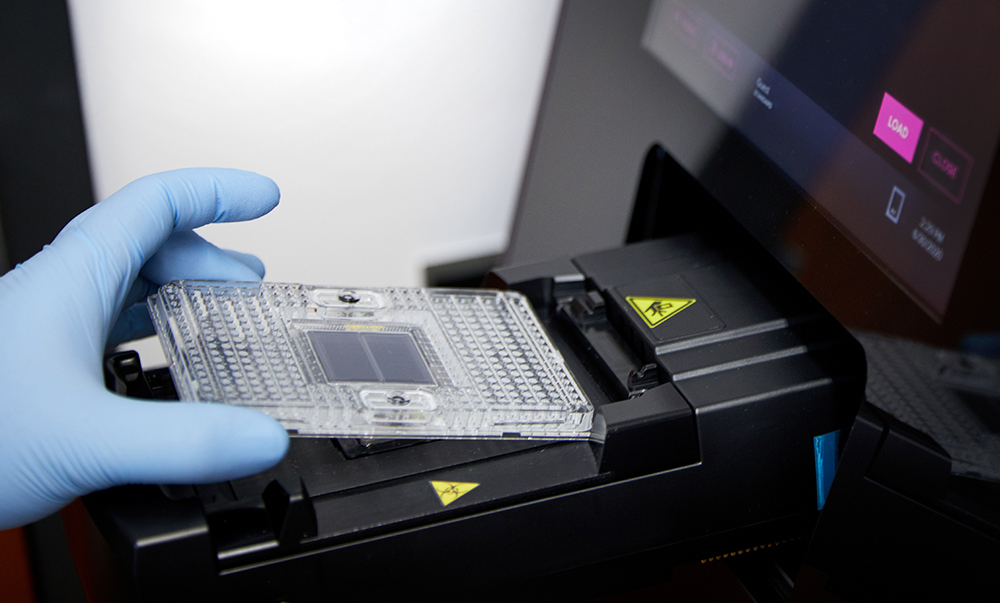

Soon other research was underway — more than 150 grants have been written since February, bringing in $16 million in funding, and WashU was selected as a major site for all National Institutes of Health clinical trials. Researchers evaluated possible treatments (hydroxychloroquine was shown to be entirely ineffective; apilomod held promise, as did convalescent plasma). And they developed a blood test to determine who had been exposed to the virus so their response could be studied; a test to determine whether a patient had cleared the virus; and saliva tests for COVID-19 that would be far more palatable than a nasal swab tickling the brain — not to mention cheaper, easier and safer to administer. Research data were posted in a continuous stream on a free international database, ignoring political agendas.

Because the chair of the infectious diseases division, William Powderly, MD, had spoken early on with Whelan and Diamond, he knew their research would require samples of blood, plasma and cells. “One thing we did early on, before many other institutions, was put together rapidly two protocols, one for the collection of specimens from patients and the second for the collection of data from patients,” says Powderly, the J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine. Soon 30 labs from around the university would be using the repository. “Through recovery, patients are continuing to come in and give us samples,” he adds, “so we can see how their immune systems are coping.”

Because he is also the director of the Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences and the Larry J. Shapiro Director of the Institute for Public Health, Powderly stands at the nexus of research, clinical care and public health. He describes how the Institute for Informatics supplied a steady stream of modeling data, helping WashU public-health experts persuade city and county officials to issue shelter-in-place orders sooner than they might have. Then the state contracted with WashU for help tracking the virus and pinpointing hot spots, and institute experts also helped city and county health departments track trends and see racial disparities, “all without fanfare and without any thought of being paid,” Powderly notes.

As Martin and Perlmutter wrote in one of their frequent letters to faculty and staff, as exciting as the vaccine and treatment research was, “Our only truly effective response right now — and possibly for some time — will come from public-health systems.”

Steven Lawrence, MD, associate professor of medicine and a specialist in infectious diseases and epidemiology, found himself answering questions for TV, radio, newspapers and podcasts, correcting myths and misinformation daily. He and other WashU specialists spent extra hours explaining COVID-19 to the general public in every way possible. Jason Purnell, associate professor in the Brown School and director of Health Equity Works, was asked to lead St. Louis’ COVID-19 Regional Response Team, more than 40 agencies and governments banding together to keep people fed, employed, housed and safe. The inequities Purnell had been documenting for years were now visible in the ICUs: St. Louis’ African American community was the hardest hit.

Other vulnerable groups were low-income workers with no viable way to shelter in place and people who were incarcerated, living in residential facilities or homeless. The university’s Center for Community Health Partnership and Research helped educate immigrants and refugees, easing the blind terror of those who had lost loved ones to epidemics in their native countries. The Social Policy Institute analyzed effects of race and gender, and documented just how surely wealth predicted the ability to practice social distancing.

Rather than sit around feeling helpless when campus closed, med students set up an email “hotline” to field questions about the coronavirus, helped the swamped St. Louis County Health Department do contact tracing and sifted through COVID-19 research that might inform clinical care. When a first-year student realized there were no COVID hotlines or websites in Spanish, she networked fast, spreading health information throughout St. Louis’ Latino community. Students and faculty who spoke Arabic and Bosnian did the same.

Researchers were also keeping an eye on related aspects of public health — like a nearly 40% drop in stroke evaluations, because people were afraid to seek help during a pandemic. A business faculty member worked with engineers at the McKelvey School to model public-health and economic repercussions of lifting quarantine at various points. Overall, a measured, gradual reopening looked healthier for both individuals and the economy than either a long, strict, economically devastating lockdown or a rapid loosening of restrictions and rapid economic recovery. Rapid loosening would likely be followed by a surge, they warned, causing three times as many deaths as the other two models.

Washington University faculty across the campuses, including experts in aerosols as well as infection and epidemiology, signed a letter, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, warning that public-health guidelines needed to extend to increased ventilation and control of airborne microdroplets. The World Health Organization referenced the letter at its next press briefing.

Reaching out

“It feels like the world as we know it has been completely turned upside down in a very short time,” Martin wrote to faculty and staff. “It’s an uncertain and scary time, and we’re leaning on each other now more than ever before.”

The sleek Knight Executive Education and Conference Center was converted to give frontline health workers and first responders a safe place to sleep between shifts — and avoid bringing germs home to their families. Food was delivered, and medical students organized childcare. Thousands of messages of gratitude and support came from other parts of the university, lighting up digital screens and a special Wall of Hope.

After fielding call after call from members of the university community eager to help those hurt financially by the pandemic, WashU created two crisis response funds, one for students and one for employees. The Office for Student Success partnered with the Learning Center to make sure students had online tutoring, coaching and mentoring, and that no one felt isolated or abandoned. One of the office’s student program coordinators, Jessica Yu, set up an informal network of people whom students could reach out to if they were stressed. Faculty members on the Danforth Campus made a video — wearing Bears sweatshirts, holding dogs on their laps and showing more bookshelves in the background than on “PBS NewsHour” — to remind students they were still thinking of them.

Because the health workers’ most urgent need was PPE, students and faculty from the McKelvey School of Engineering, the School of Medicine, Arts & Sciences and the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts collaborated to create supplies and equipment. A Maker Task Force designed and arranged for the manufacture of prototypes designed specifically for the pandemic, including face shields, isolation gowns, cloth masks and even second-generation emergency ventilators.

Mindful of stresses on the local economy, the university donated $100,000 to local COVID-19 response efforts. It also honored every contract, helped the owner of a fitness studio move classes to the West Campus open-air garage, and bought more than 1,500 meals every week to stabilize surrounding restaurants and feed the employees who were scrubbing down facilities, working in IT and security, and keeping the Medical Campus running.

A professor at Olin Business School helped restaurateurs decode the federal stimulus package. Olin undergraduates launched a pro bono consulting service for small businesses, and faculty at the Brown School offered free professional development to local nonprofits. A graduating senior founded Rem and Company — using the name of the vivid-dream stage of sleep to match the nightmare of COVID-19 — and networked students and professionals across the country to consult with small businesses.

Because kids were now home with parents who were not quite sure how to teach them, the Institute for School Partnership came up with remote-learning lessons and fun STEM activities. Two graduating seniors founded Learning Lodge, a free online tutoring service, rounding up 168 volunteers who had “run out of Netflix shows” and were eager to do something useful. A neuroscience grad trained student volunteers for a program called Students to Seniors, so they could do virtual visits with older adults who were now more isolated than ever, cut off from family visits and eating meals in their rooms. “We must guard their humanity and dignity,” founder Harsh Moolani said, adding that “now, more than ever, we can all benefit from their wisdom.”

With STL Food Angels, students offered free, contactless grocery delivery to St. Louisans who were at risk or already ill. Psychology major Han Ju Seo set aside her sadness over graduation being canceled and, inspired by a professor’s research on the link between happiness and altruism, sewed 1,000 masks for the St. Louis community.

“It is the most extraordinary thing to watch all of you — our faculty, staff and students — harness your ingenuity and drive to meet this enormous challenge. Every day we see new ways that many of you have extended beyond the usual and volunteered to help on the front lines or behind the scenes,” wrote Dean Perlmutter and Chancellor Martin in one of their frequent letters to faculty and staff. “There will be more of those who need us in the coming days and weeks, and because of all of you, we will respond.”

A long, hot, lonely summer

At the end of May, St. Louis City and County reopened. Students, as well as graduating seniors, were invited to return to campus for the rest of their belongings, if they liked; otherwise, everything would be stored or shipped, free of charge.

The student life offices felt desolate. These staffers were the extroverts of campus, used to popping in and out of offices, hatching ideas together. “For all of us who work closely with students, having that in-person contact taken away has been absolutely devastating,” Wild said in July. “We are feeling lonely, and our students are really feeling the loss. College is stressful, and there’s hard work to be done, but there’s also friendship and concerts and fun. There’s no fun in this.”

Instead, the summer was quiet and strange, the mood resolute. “We had to take care of not only the health crisis, but also our financial crisis at the same time,” Perlmutter says. “And that’s as hard as it gets.” Between March 1 and April 30 alone, the Medical Campus had lost more than $60 million in revenue, and the medical school was projecting a revenue loss of more than $150 million by July. Hundreds of hospital beds were empty, and the clinics were seeing 60% fewer patients. Due to the med school losses, university refunds (for housing, dining, parking and other fees) and unforeseen pandemic costs, the university’s next fiscal year would show an unexpected loss of roughly $500 million in revenue.

The forecasted loss in revenue would impact the university’s ability to achieve its mission and provide the excellent service for which it’s known. So dramatic cost-saving measures were implemented. A hiring freeze went into effect, top administrators took pay cuts as high as 20%, merit raises were canceled and budgets slashed, and 2,000 employees were placed on a furlough strategically timed to end July 25. That was when the federal CARES Act was set to expire — and with it its weekly $600 COVID bonus on top of unemployment. To make sure as many employees as possible could return from furlough, the university freed up $95 million by temporarily suspending its employee retirement match.

All summer, the Fall Planning Committee held intense meetings. A large, diverse student body in lively, dense contact with one another and with professors and staff — again, the very nature of the university — was part of the challenge.

Most private universities were planning an early start. Conscious of how fluid and change-able the situation was, WashU pushed its undergraduate semester’s start back and staggered graduate and professional schools.

“We wanted as much time as possible to learn what works and what doesn’t work on a college campus,” Martin explains. “So we decided to move slowly, which some folks understandably found frustrating. But it gave us the best shot at doing this right.”

On July 31, the university confirmed that, with strict protocols, the campuses would reopen. The fast, affordable saliva test developed at the medical school would allow frequent monitoring. The pandemic’s course would also be monitored, an alert system used, policies continually re-evaluated. Fewer students would live on campus, and all would have single rooms; if there were extenuating financial circumstances, the university would provide housing. Provisions would be made for quarantine. Some classes would be predominantly online, some predominantly in-person, and quite a few would be hybrids, keeping the choice flexible for students.

Happily, many of the faculty members who had pivoted to online after vehement protest were beginning to see a few advantages. “Some students thrived, because they felt less pressure; they could review the material at their own pace, replay or play on a lower speed,” Wysession says. “And students who used to hide in the back of the class were participating more, because online, all 15 students are equal. Everybody’s in the same-size box.”

But the hybrid model posed fresh challenges: Students in the classroom had to be able to see and hear those online, and vice versa.

“We spent over $1 million to put cameras and mics in 123 large, higher-tech classrooms,” Wysession says. “And the chancellor is making sure every undergraduate has a laptop.”

Testing methods were rethought, because with long, closed-book, high-stakes exams, the safeguards against cheating online are too Orwellian. “When you think about what you want your students to be able to know and do, that’s usually not the best method of assessment anyway,” Wysession notes.

Over the summer, faculty had recorded some of their lectures. Center for Teaching and Learning staff turned several classrooms into studios, with remotely controlled cameras following their movements from a distance. Creative tips and best practices were shared across disciplines. The Fossett Lab’s augmented reality app, for example, had been developed for geophysics, but it will allow students in many disciplines to explore 3D objects remotely.

Wysession hopes this level of collaboration will continue well beyond the pandemic. “Too often,” he notes, “we’d been reinventing the wheel all across campus.”

And Perlmutter feels the same way about the discipline, flexibility and altruism he has seen at the medical school. Asked if they were willing to take on new clinical roles, more than 700 members of the clinical faculty responded with an immediate yes. Others volunteered to cover new units in the hospital whenever necessary. And researchers performed with unprecedented focus and collaboration. “It builds your confidence,” he says. “We now know we can leverage this massive research engine to solve the most important problems facing the world.”

“We have really come together to deal with this. We are redefining community.”

Kawanna Leggett

And the all-important challenge of restoring the fun and energy of student life? With the help of resident assistants in the dorms, small virtual communities were created, explains Leggett. Staff planned dozens of smaller experiences that would capture the fun of college life safely, “with more activities either virtual or outside, in nature.” Friendships made in those tight groups could wind up even stronger. “We have really come together to deal with this,” she says. “We are redefining community.”

Wysession was thrilled to hear that campus would reopen. “Students have made it clear: Many don’t care so much if classes are online or in person, but they all want to be here.” It’s the social part of college they miss most desperately. “And with Black Lives Matter and the country’s social justice awakening, many students have been protesting all summer in their hometowns. We want to provide the opportunity for furthering those discussions.”

“While this will be a semester like no other,” wrote Chancellor Martin and Provost Beverly Wendland when they announced the fall plans, “rest assured we are still WashU.”