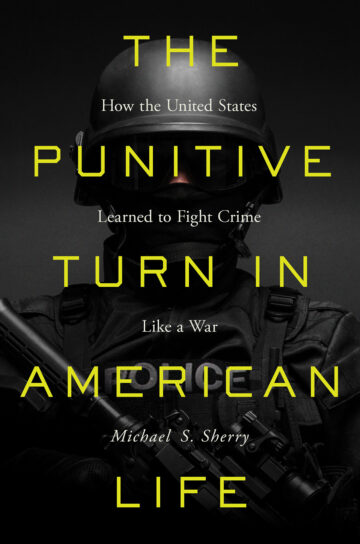

Michael S. Sherry, AB ’67, the Richard W. Leopold Professor of History Emeritus at Northwestern University, shares an excerpt from his forthcoming book The Punitive Turn in American Life: How the United States Learned to Fight Crime Like a War (University of North Carolina Press, December 2020).

Advertisements urging civilians to buy guns captured how the punitive turn had played out by the 2010s. “As Close as You Can Get Without Enlisting” — that is, get to war — ran one rifle ad, while another ad promoted a semi-automatic shotgun with the slogan, “Iraq, Afghanistan, Your Living Room,” and a handgun ad pictured an infantryman above the words, “Built For Them… Built For You.” Their message: Americans at home could carry the same weapons of war that soldiers carried in battle. Many Americans believed, or at least were asked to imagine, that the line between war-fighting and crime-fighting had almost disappeared. This book is about how that happened.

Its title refers to the sweeping process that moved punishment and surveillance to the center of American life and imbued them with militarized language and practices. Obvious forms [of punishment and surveillance] were mass incarceration, as the United States became the world’s foremost jailer, and “the militarization of policing,” as critics called it. But the punitive turn also encompassed other practices — public schools patrolled by police, gated communities shooing away the unwanted, cameras peering at red-light offenders, armies of private police, familiar rituals of airport screening, and fads like the child-spanking movement. Scholars often refer to “the carceral state.” The “punitive turn in American life,” signals a broader historical process that included but went beyond what the state did.

The Punitive Turn in American Life

How the United States Learned to Fight Crime Like a War

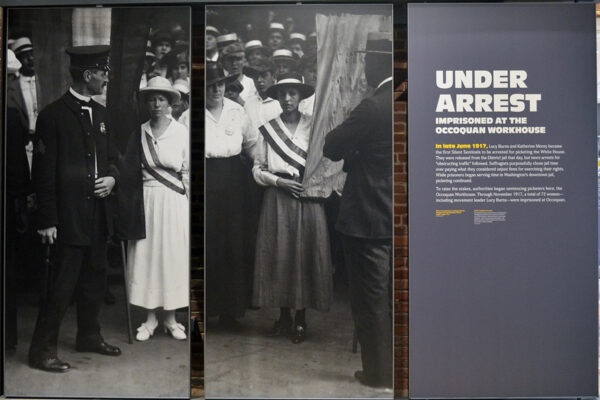

In the 1960s, political leaders, managing a state under siege as America’s Vietnam War faltered, embarked on a war on crime in order to reassert the state’s legitimacy, to preserve their power, and to quell the era’s disorder. They started a process whereby resources devoted to war and national security were partly redeployed to wage “war on crime,” to use the term that became commonplace. Redeployment was often halting, improvised, half-intended. But when President Lyndon Johnson proclaimed on Sept. 22, 1965, that “the policeman is the frontline soldier in our war against crime,” the process was starting. By then, an already substantial machinery of law enforcement and a powerful apparatus of national security provided the state the capacity to act vigorously in criminal justice on militarized terms. Soon, the waning of America’s war in Vietnam created a surplus of war-making capacity that was recycled into crime-fighting, and responses to crime got encased in the language and institutions of war-making. Each subsequent U.S. war recapitulated the process, pouring a new wave of veterans, weapons and attitudes into the criminal-justice system. Under federal give-away programs starting in the 1960s, even small cities and colleges acquired armored personnel carriers and muscled, militarized SWAT teams. Liberal, moderate and most of all conservative leaders worked to rebuild the state, basing it on a new punitive order that borrowed from an older militarized way of life.

The Cold War’s end widened these developments. With hundreds of military bases downsized or abandoned, denuding local economies, officials eyed them as places to stash more inmates, while locals sought new opportunities for jobs and economic development. Drive along US-31 near Kokomo, Indiana, for example, and spot the Miami Correctional Facility, built in the 1990s on the edge of the once-giant Grissom Air Force Base — a prison that one reporter likened to a “high-tech POW camp.” Perhaps it looked that way because its first superintendent, who helped design the prison, did double duty as a commander of the Army Reserve’s 300th Military Police Command, whose task “in wartime” was to “set up barracks for enemy POWs,” as he soon did at Guantanamo and in Afghanistan. Dozens of prisons sprouted on demobilized bases — the logical places for them for those who imagined criminal justice as a “war on crime.”

Intwined with systemic racism, the process yielded startling levels of incarceration, militarized borders, torture stateside and abroad, and much else. No wonder Americans kill each other so often, and police kill “civilians” so often. They had been taught for decades to view crime-fighting as akin to war-fighting. President Barack Obama pushed back against that attitude, but to little avail. “We have to stop treating people like we’re in Fallujah,” one police officer (and war veteran) commented to The New Yorker in 2018, referring to the Iraqi city which in 2004 saw the Iraq War’s bloodiest fighting for U.S. forces. “You sometimes hear cops talk about people in the community as ‘civilians,’ but that’s bullshit… We’re not the military.” But many Americans, including President Donald Trump, think they are. Even as their wars abroad dragged on inconclusively (at best), they seem inclined to use the machinery of criminal-justice to wage war with each other.

You can pre-order the book at the University of North Carolina Press or on Amazon.