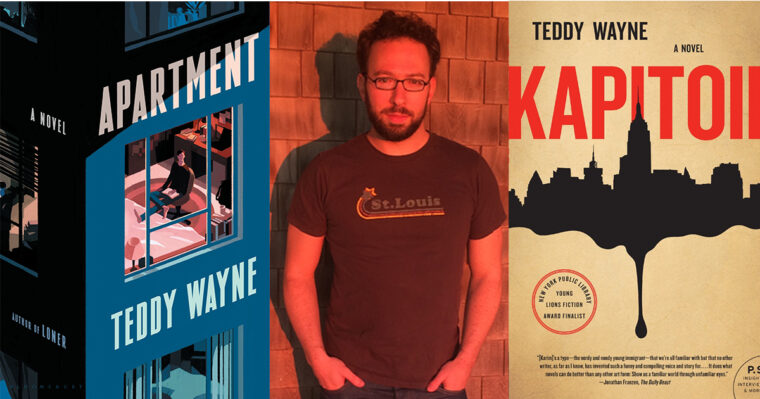

Successful novelist Teddy Wayne’s first published novel, Kapitoil, was written as a grad student in WashU’s distinguished MFA in Creative Writing program, but it almost didn’t happen. During his first year in the program, Wayne’s work was not well-received by classmates during writing critiques, and he seriously considered giving up to pursue another career.

In Wayne’s fourth and latest novel, Apartment, the isolated protagonist happens to be in grad school working toward his MFA in Creative Writing. He endures unsparing critiques from professors who favor certain students and classmates who relentlessly point out the shortcomings of his work. Is there a connection? Actually, no. Wayne, MFA ’07, is quick to acknowledge this was not based on his WashU experience, although his first-year trials did factor into the character’s writing struggles. “When you go into graduate school, the impression you often get, which is what I depicted in the novel Apartment, is that professors can play favorites, and it can be cruel and cutting. That wasn’t the case at all at WashU. They were all incredibly supportive, generous and friendly. It was a very nurturing environment,” Wayne says.

Thanks to the guidance of his writing professors — particularly Kathryn Davis, Hurst writer in residence; Marshall Klimasewiski, senior writer in residence; and former faculty member Kellie Wells — Wayne soon reached a new level of confidence in his writing, fully prepared to take emotional risks. “I started working on Kapitoil in the middle of that year, and that was the first time I showed any kind of vulnerability in my work. It was in part because I was working with feelings I had, even if they were transposed onto a character very different from me,” says Wayne, who also taught writing at WashU during his second and third years of graduate school.

Although Kapitoil, the story of a man from Qatar working for an oil company in pre-9/11 New York City, did not sell during grad school, Wayne revised it heavily and sold it after graduation. He still remembers getting the news. “I was in my apartment in Stuy Town, where the novel Apartment is set. It was exciting, probably the highlight of my professional life.” Wayne has since been hailed as one of today’s most extraordinary writers, seeing through the strata of American life with remarkable clarity and achieving a deeply affecting emotional resonance in his work.

Currently Wayne, whose novels also reflect his exceptional descriptive talent, is addressing the challenge of adapting his work for the visual medium of television and cinema. The Love Song of Jonny Valentine — where an 11-year-old St. Louis boy becomes a global pop phenomenon — has been optioned by MGM, and Wayne has already written the pilot. He’s also written a screenplay for the cinematic version of Apartment, which is in negotiation.

“Writing for the screen is a related skill, but it’s a separate one too, in that you have to think visually and economically,” Wayne explains. “Often you have to completely change the dynamic and go from what would be a static, lifeless scene to making things pop visually, making something happen in a big way that expresses what you’re trying to get at in the scene, which takes a radical rethinking of it.”

In addition to these irons in the fire, Wayne is a frequent contributor to the New York Times, New Yorker and McSweeney’s, and he is at work on his fifth novel. Has all this success made it easier for Wayne to write subsequent novels? “No, it gets harder,” Wayne says. “You don’t want to repeat yourself, so you have to figure out ways to do something new while still telling a completely new story.” Yet Wayne’s novels have done just that. From a Qatari computer programmer thrown into the world of Wall Street (Kapitoil), to an isolated young man’s descent into anger and confusion while attending Harvard (Loner), to the two writers who find their friendship dissolving in the confines of a small space (Apartment), Wayne continues juxtaposing characters with their environments in revelatory ways, while blending dynamic fictional elements with his own personal experiences.