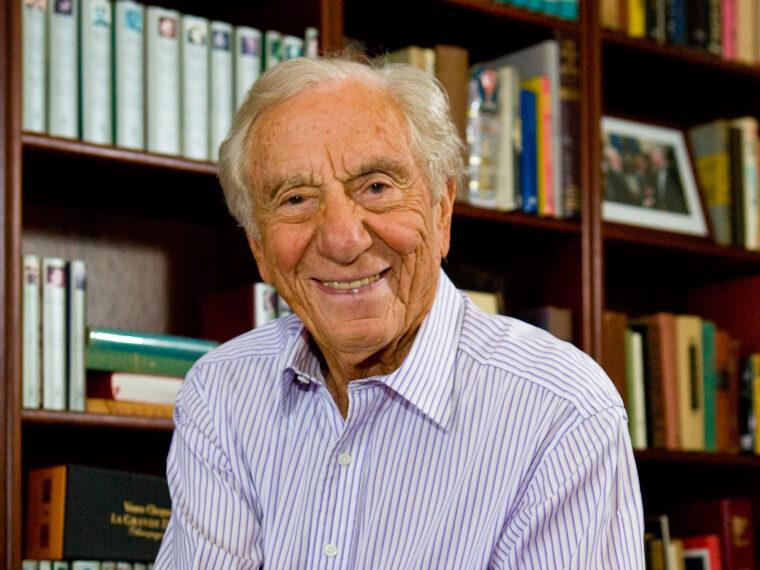

“A.E. Hotchner was my father,” I mumble into the pillow before slipping into sleepy unconsciousness. Of course, this is untrue. I have just received the terrible news that Hotchner has passed away, and in those seconds as I lose my hold on the real world, this is how he appears — gentlemanly, humane, elegant, smiling, always forgiving, an apparitional father-figure.

We have been friends for more than thirty years, but of course, I have never expressed such feelings — nor have I even expressed them to myself before this liminal moment between sleep and wakefulness, having learned about Hotch’s death at the remarkable age of 102.

When we met for lunch at the Russian Tea Room, at his literary club on 43rd Street off of Fifth Avenue, or Elaine’s when it was still operating, Hotch would always asked about my story, not tell me his. He wanted to know how things were going in the Performing Arts Department at Washington University in St. Louis, where he had such deep personal associations and feelings — never speaking about himself or his next project. When I proposed naming our Studio Theatre after him in the mid-1990s, he immediately refused the honor. It was only after several requests, all met with similar refusal, that I presented it as a fait accompli that he accepted, grudgingly. Shortly thereafter, he returned to his alma mater to attend the Washington University Performing Arts Department’s production of Café Universe, Hotchner’s own dramatic adaptation of several Ernest Hemingway stories woven into an evening-length performance. Two of Hemingway’s sons attended the premiere performance as the newly dedicated black-box theatre was, for one night, transformed into the grubby railway café called for in the script — and where Hemingway’s oldest son, Jack, demanded real whiskey, which we accommodated out of plastic cups in contravention to the university’s regulations.

When Hotch did speak about his own work, it was never about his own writing, which was voluminous. He continued to write throughout his life, and his novel The Amazing Adventures of Aaron Broome, was published after he celebrated his 101st birthday. Instead, he liked to talk about the Newman’s Own Foundation, the charity he and his dear friend Paul Newman started — by accident! — after they whipped up a batch of spaghetti sauce in Newman’s kitchen in Westport, Conn., and decided to turn it into a multi-million dollar foundation that annually donates all its proceeds to children with life-threatening illnesses, as well as other worthwhile causes. Hotchner grew most animated when I asked him about Newman’s Own and especially the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp. Each year, he would write a musical to benefit the camp, which grew into an international phenomenon and inspiration, sponsoring some thirty camps — all benefitting sick children, offering them a holiday at no cost. Each year, the musical drew mega-stars of the stature of Julia Roberts, Alec Baldwin and Matt Damon — in addition to Paul Newman and his wife, Joanne Woodward, of course — to a gala performance to raise money for the camps.

In thinking about the man who asked me to call him “Hotch” at our first meeting in New York, I reflect upon the fact that this man, who gave away so much, began with nothing. His memoir of growing up in Depression-era St. Louis in the 1930s, King of the Hill, is a masterpiece in the genre of memoir, and was turned into a great film by Stephen Soderbergh. Anyone who reads that book or sees the film will understand the meaning of Hotch’s life, a life extraordinarily well-lived. Hotchner literally transformed himself from an orphan into an artist/biographer/philanthropist who gave away millions to worthwhile causes. His biography, Papa Hemingway, reveals the remarkable fact that Hotch, who has been father to so many children in need (in addition to three children and step-son of his own), was in search of a father himself. His own father had abandoned both he and his younger brother in a cheap St. Louis hotel to eke out a living as a traveling salesman selling candles door-to-door. But unlike so many tell-all memoirs that seek to re-litigate the past, Hotchner’s King of the Hill is a hymn to survival and triumph, not bitterness or regret. Perhaps its harshest sentence comes in the form of this gentle rebuke from the memoir’s child-narrator; “I thought that was pretty stupid of my father to trot out those stupid candles and ring all those stupid bells and get pushed in the face by all those really stupid people.”

In these times of division, recrimination and self-absorption in which we live in today, the life of A.E. Hotchner deserves special celebration. His altruism was of a kind that never sought credit or acclaim. Rather, his unselfishness is a reminder that each one of us has the opportunity to remake ourselves in a way that is unique and can truly make a difference.