In her course “Disease, Madness, and Death Italian Style,” Rebecca Messbarger, professor of ltalian and founding director of the Medical Humanities Program at Washington University, takes students through seven centuries of Italian culture, beginning with The Decameron and the plague of 1348.

Students — many of whom are pre-med — examine how Italian society, heavily rooted in Catholicism, reasoned with an event that decimated as much as half the population. The course then explores how Italian society, across seven centuries, has viewed health, illness and medical care against the backdrop of such mortal threats as disease, madness and death.

“In a literature course focusing on the experience of illness and care, it’s not about data. It’s about humanity, and that’s one of the things these students ponder,” says Messbarger, who is an affiliate professor in history; art history; international and area studies; performing arts; and women, gender and sexuality studies.

“Medical care is more effective today in treating disease than at any time. Yet, paradoxically, there is rising discontent on both sides of the stethoscope, due to a kind of lost humanity. Patients often distrust the medical system, and there is dissatisfaction and even despair among medical students, residents and doctors in the way they have to approach health care,” Messbarger says. “My hope is that through a course like this and others in the medical humanities, we might cultivate practitioners who demand that medical education and clinical practice prioritize the human experience at the veritable heart of medicine.”

THE MANDRAKE

The mandrake plant captured the imaginations of writers and artists during the Italian Renaissance, and a variety of myths surrounded the plant’s “magical” properties. With roots resembling a human figure, the mandrake was highly sought after as a fertility enhancement, aphrodisiac and anesthetic — although it is, in fact, poisonous to humans in large quantities. In Machiavelli’s 1518 comedic play, The Mandrake, the author depicts a scheme — centered on superstitions around the mandrake — to lure a woman away from her husband. Common myths about the mandrake included it making a deathly shrieking sound when uprooted as well as it growing from the blood of hanged men.

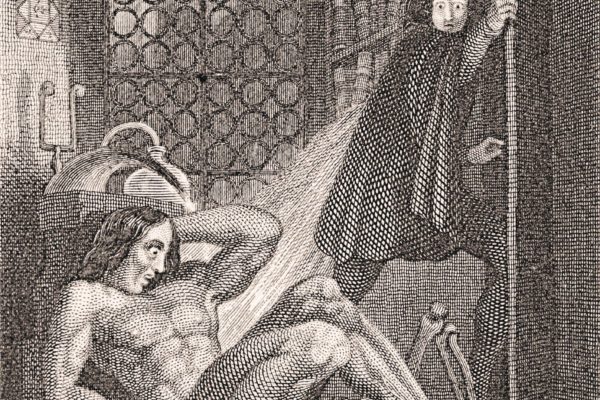

CUTTING OPEN CRIMINALS

Until the 18th century in such centers of medicine as Bologna and Padua, body “donors” dissected at the annual Public Anatomy were executed criminals. The event was also called the Carnival Dissection because it took place during carnival in late January or early February, not coincidentally the coldest time of the year. It could be risky business for the Professor Anatomist, due to controversy about dissecting human cadavers. In Bologna, the anatomy lesson devolved at times into shouting matches, assaults on the anatomist and even vandalism of the cadaver.

EARLY HEALTH CARE

Modern hospitals originated in the medieval hospital movement led by charitable Christian orders, which, as in the case of the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Rome (founded in 727 and still serving Romans today), cared for the poor and infirm, and provided lodging, food and rest to those on holy pilgrimage.

MIDDAY MADNESS

Noon, the hottest part of the day, was believed to be a time of metamorphosis. In the epic poem “Orlando Furioso” (“The Frenzy of Orlando”), a love-sick knight falls into madness (at noon) after being rejected by his not-so-chaste lady love and goes on a rampage through Europe and Africa, destroying everything in his path.