In a Dec. 10 briefing on Capitol Hill, a Washington University in St. Louis expert testified that steep price increases and “supply shocks” in helium threaten basic research in academic settings and also broader health and industry applications.

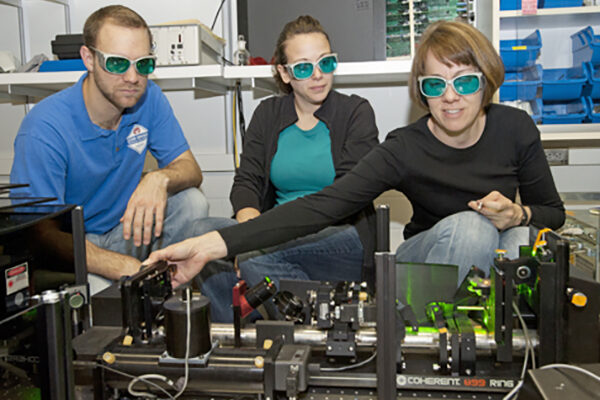

“Helium is ubiquitous in our lives,” said Sophia E. Hayes, professor of chemistry in Arts & Sciences, in written remarks to a subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives. Hayes spoke and answered questions in a session titled, “Research and Innovation to Address the Critical Materials Challenge.” Helium is one of 35 identified critical elements, added to a U.S. federal list of such minerals in 2018.

“From its use in cooling MRI machines in medicine; to the launch of space missions and pressurizing rockets’ fuel systems; its use in weather balloons; the production of semiconductor chips, flat panel screens and optical fibers that dominate our electronic ‘lives’ and handheld devices; and as a critical element in red lasers — helium is essential for each one of those processes,” Hayes said.

The precious and limited natural resource of helium enters our everyday lives with scant notice: sustaining life-saving diagnostic tools such as hospital MRI machines, cooling scientific research equipment and fiber optic internet access.

But all of these important uses are threatened by the lack of a reliable helium supply. Hayes testified that without a constant and reliable flow of helium for cooling, laboratory equipment that costs anywhere from $100,000 to $15 million per unit can heat up and be destroyed — threatening basic science research. Student educational opportunities and outcomes can also be negatively affected.

“What we have faced in the past two decades is steep price increases, and supply ‘shocks,’ where helium could not be acquired in some cases at any price,” Hayes said.

“The U.S. Strategic Helium Reserve, which is scheduled for shutdown in fall 2021, is central to these supply shocks,” Hayes said. “Having an inventory helps during supply interruptions from other major world helium-producers: Qatar and Algeria, and soon, Russia. The reserve currently supplies more than 40% of domestic demand. But Congress also has decided that private industry should step in when the reserve closes. This has not happened to-date.”

Academic institutions — of which Hayes estimated there may be up to 1,000 in the U.S. using helium — aren’t the only places with researchers in need of the resource. She said “every pharmaceutical company, every research and development arm of oil and gas companies (such as Exxon Mobil, Chevron), every chemical-producing company” requires helium for their research, too.

Hayes provided recommendations for two broad courses of action: stepping up activities to improve helium recycling — as she and others have done in certain research facilities at Washington University — and postponement of the planned 2021 shutdown and sale and/or privatization of the Strategic Helium Reserve.

“We have had several major supply shocks in my career, and multiple minor supply shocks,” Hayes said. “If you’ll permit me to use another analogy, we are like cattle ranchers. We have a handful of magnets in our ‘herd’ that will die during a drought. If they die, these magnets never come back. We can buy new ones, certainly, a massive capital expenditure — but know that we will face future droughts that will ‘kill off’ the herd again.”

Hayes’ testimony begins at the 27:35 mark, and she also answers questions as part of the panel.