A Washington University education does more than teach. It inspires. And one of Washington University’s most remarkable traditions — bringing in prominent speakers on an almost weekly basis — is meant to do exactly that.

With the long-standing Assembly Series (which began nearly 70 years ago), annual Commencement and recognition ceremony addresses, as well as academic, student and alumni events, the university delivers, in any given year, a stellar lineup of speakers. Further, students have the opportunity to interact with these thought leaders during their time on campus. Cumulatively, these opportunities represent an education within an education — a chance for students to engage with big ideas, all within the day-to-day routine of student life.

These lectures remain a hallmark of the WashU experience, ever broadening our perspective. For many students, they also have had a transformative impact. Below, we examine the special significance that three prominent guest speakers had for our alumni and faculty, and hear just a bit from their inspirational talks.

Lessons from the past

Alex Haley

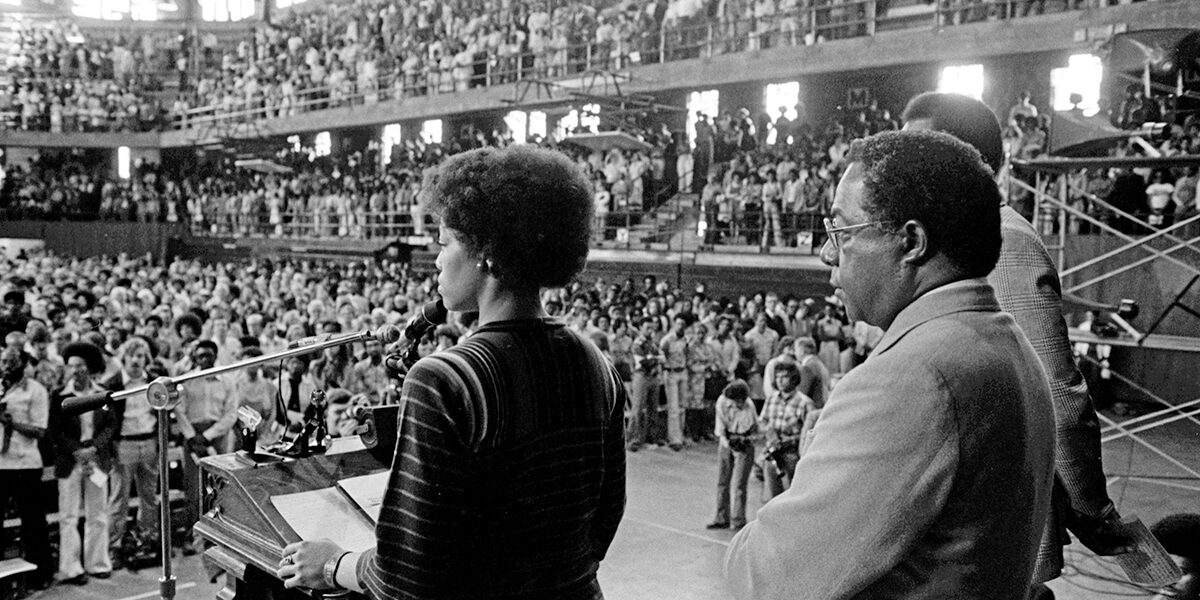

Alex Haley, author of the hugely influential novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family, came to campus in 1977 and again in 1990, each time exerting a great influence on the students he interacted with. His March 30, 1977, lecture was a major event, as Roots had been published less than a year before and the television miniseries based on the novel had aired only two months earlier. The novel was also then being translated into 22 languages to be read around the world.

Haley’s lecture was held in Washington University’s Field House to accommodate the large interest expressed across campus and in the St. Louis community. Local school kids took field trips to attend, and a special session with the press was arranged as well. At the time, Jan Taylor, AB ’77, PT ’79, was a senior serving as president of the program committee of the Association of Black Students (ABS) and played a key role in organizing the lecture and the Martin Luther King Jr. Symposium surrounding Haley’s talk.

“When you’re young, you think they’re just stories; but as you get older, you realize they were more than that. They were stories that happened. And they happened to people whose blood continues to flow through my veins.”

— Jan Taylor

For Taylor, the novel Roots meant legacy, and she was able to relate it to her own family’s stories. Her great-grandparents were the children of sharecroppers, and her great-great-great grandparents had been slaves. “It helped me connect those dots better. When you’re young, you think they’re just stories; but as you get older, you realize they were more than that. They were stories that happened. And they happened to people whose blood continues to flow through my veins,” says Taylor, now a retired physical therapist in Baltimore. “That’s what Roots did to me. It gave me pride in who I was, but also a sadness, realizing what my great-grandparents’ parents, and their parents, had to go through so I could live.”

Her fondest memory of the day Haley came to campus was not the speech itself but meeting Haley, as she and a few other very excited ABS students picked him up at the airport. Given the powerful influence of his book, she was struck by how humble, quiet and peaceful Haley was, a man content with his own thoughts. “He didn’t have to say a word because that power came through his gift, which was in writing and dreaming and investigating and sharing that knowledge with millions,” Taylor says. “It let me know at a young age that it wasn’t about who you talked yourself up to be; it was about the gift you had inside.”

Taylor, who has kept a framed photo of herself and Haley ever since, remarks on the transformative impact Haley’s visit had on her career and her life. “He impressed me so much that I began to reflect on just keeping quiet, taking time to think and allowing myself to dream. Talking too much may keep us from seeing other awesome possibilities and from being able to have a conversation with ourselves.”

“That was the most powerful impact Alex Haley had on my life. He basically sparked my interest in learning more about my own history, emphasizing that you have to be that living witness to carry it forward or it just dissipates.”

— Kevin Foster

Alex Haley returned to the university in 1990, inspiring another generation of WashU students, including Kevin Foster, BSAS ’93, MBA ’98, then president of the ABS. In a conversation during a luncheon, Foster asked Haley what had inspired him to write Roots. Haley told him it was the stories he had heard as a child, sitting on his front porch listening to his grandmother, his aunt and his mom, that sparked his ancestral research. Haley then asked Foster to go home and talk to his great-grandmother about his own family. Foster says, “It was the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done, because based on that conversation I learned that my great-grandfather started a teaching school in Texas that turned into Butler College, which was later dissolved in 1972.

“That was the most powerful impact Alex Haley had on my life. He basically sparked my interest in learning more about my own history, emphasizing that you have to be that living witness to carry it forward or it just dissipates,” says Foster, senior director of product marketing for a Boston-based technology company. “Now that I am a father of two children, it’s incumbent on me to talk to them about my ancestry, so they may know who helped make them who they are today.”

The quest for equality

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has, across several decades, been one of the most effective advocates for equal rights. Her two visits to Washington University — in 1979 and 2001 — greatly enhanced the dialogue around equality on campus. Ginsburg (now popularly referred to as RBG) met with students and faculty, lectured and even contributed journal articles to the Washington University Law Quarterly (1979) and Washington University Journal of Law & Policy (2001).

In February 1979, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg first came to campus, Susan Frelich Appleton, the Lemma Barkeloo and Phoebe Couzins Professor of Law, was a young faculty member. Ginsburg, then a Columbia University professor, participated in the School of Law’s Quest for Equality series, which consisted of nine panel discussions on equality during the 1978–79 academic year. (Future Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School at the time, participated in the series as well.)

Appleton recalls Ginsburg’s 1979 visit: “She compared two paths to gender equality: the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment and the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. Noting the uneven success to date of litigation under the former, she strongly advocated the latter as the more certain alternative.

“Keep in mind that her talk took place only a few months after the ERA’s most ardent and famous opponent, Phyllis Schlafly, had received her JD degree from our School of Law,” Appleton adds. “Although Schlafly prevailed in her quest to prevent the ERA from becoming part of the Constitution, the Equal Protection option turned out to be a very successful path after all — in large part because of RBG’s efforts as a lawyer, scholar and justice.”

Ginsburg returned to WashU in 2001, this time as a Supreme Court justice. For several days (including International Women’s Day), she took part in the jurist-in-residence program, spoke to a law class about women in the Supreme Court, met with faculty, and delivered a public lecture. Mia Eisner-Grynberg, AB ’04, then a first-year undergraduate and now a federal public defender in New York, attended RBG’s lecture and met her afterward.

“As a 19-year-old, it was an unbelievable thrill that I could even be in the same room as such a person. I remember her being particularly kind and interested in us and in our lives even as college freshmen,” Eisner-Grynberg says. “Even as a lawyer now, I don’t have those opportunities to meet a Supreme Court justice; very few people do. I was always thankful to the university for giving us that access.”

Celebrating our humanity

Elie Wiesel

Holocaust survivor, Nobel laureate and acclaimed author Elie Wiesel visited Washington University four times across more than 40 years (1970, 1978, 1992, 2011), sharing his insight with several generations of students.

In his last visit, Wiesel was the Class of 2011’s Commencement speaker, leaving a lasting impression on those in attendance. Among them was alumnus Adam Pearson, DOT ’11, an admirer of Wiesel’s books, especially Night. “Learning about the experience of Wiesel’s father in the concentration camp really helped open my eyes about the scope of what happened during that time,” Pearson says. “I was struck by the horrors of the Holocaust but also the power of recognizing your place in the grand scheme of things and appreciating what you can bring to the table by leveraging your past.”

On that warm May morning in Brookings Quadrangle, Wiesel talked of maintaining his faith in humanity despite all he had experienced, and he shared one of his favorite lines from Albert Camus’ The Plague: “There is more in any human being to celebrate than to denigrate.” Pearson, who was seated in one of the front rows for Wiesel’s address, recalls: “Wiesel spoke without notes about the topics of love and acceptance and grace. I remember sitting in my seat, just blown away.”

On occasion, Pearson still reflects on the impact Wiesel’s humanitarian message had for him, especially in light of his work to help the chronically homeless in the St. Louis community and as manager of strategy for the Brown School’s Envolve Center for Health Behavior Change (a partnership with Centene and Duke University). “At the Brown School, we talk a lot about diversity and inclusion and the ability to elevate the voices of those around us who have not been treated fairly or don’t have agency themselves,” Pearson says. “So every once in a while, I think about his words, about celebrating the good in people and not re-creating what was in the past.”

Pearson also admires the courage it took for Wiesel to write about his experiences and apply what he learned to the future: “Those who survived have a story to tell. And there’s some sort of obligation, as unfair as that is, to tell that story — to be a witness and let us know that we can be better than we currently are.”