The first Toni Morrison novel I read was “The Bluest Eye,” assigned in my 11th grade English class. Pecola’s world haunted me. The second Morrison novel I read was “Sula.” It was assigned in one of my black literature courses in college, and the worlds of Nel and Sula, based in a black town in Ohio, encased me in a lifelong love between two black women I had never seen represented. But the book that made me realize Morrison had a grip on me was “Paradise.” It’s about an all-black town founded in rural Oklahoma, and it took me three tries to get past the first 18 pages. It was the summer of my senior year in college, and this was the first time I read a Morrison novel of my own volition. And those first 18 pages, filled with dense, abstract prose that left me confused in its violence and beauty was no match against the lure of the summer I turned 21. I found that beginning to be difficult yet, every few weeks, I was compelled to return to the book, start from page one, and try again. Finally, on the fourth attempt, I got past those pages and firmly entered the town of Ruby, and it was the first time in my life where the thinning pages in my right hand made me anxious because I knew I was approaching an end I did not want to come.

On Aug. 5, 2019, Toni Morrison — writer (novels, essays, and children’s books), mother, playwright, lyricist (for a musical and an opera), teacher, editor — died at the age of 88. Although she lived a full life, 12 years shy of a century, I assumed she would live forever. A silly thought, I know. And as I reflect on Morrison’s life and the gems she allowed us to behold, I can’t help but think how strange it is to have a living legend die because with legends, we assume they will be and produce forever. Since their work is timeless, we fail to remember that there was a before them, that, once upon a time, their work did not exist in any canon or discography. Yet with their death, we are reminded that if there is a beginning, then there must be an end. That reminder of reality hurts as much as it feels odd. It’s a lot like the crushing effects of love, which Morrison, placed in the voice of a preacher in “Paradise,” revealed: “Love is divine only and difficult always.”

See also:

Threaded throughout all of her work, Morrison illustrated the divineness and difficulty of love. Whether that existed in the phrases former slaves used in their narratives to conceal particular atrocities; black people taking flight in spite of the physical and psychic entanglements of racism, gender oppression and classism; or black children returning from the dead to seek justice, Morrison divined the spaces of black love, black hate and all of the black in between. And whether or not you found it difficult or uncomfortable, she made you confront it with word arrangements that arrested you in their beauty. In her work and in her life, she made space for black people in her capacity as an editor for Random House, an essayist, a novelist, an artist and gatherer of black history. In an interview for her 1986 play “Dreaming Emmett,” she explained: “I take scraps, the landscapes of something that happened, and make up the rest.” Perhaps that was her greatest gift to us, her magnificent wield of imagination that has gripped us, kept us and will continue to do so. “The Ancestor lives as long as there are those who remember.” Who Toni Morrison was and what Toni Morrison gave us, we can’t help but remember.

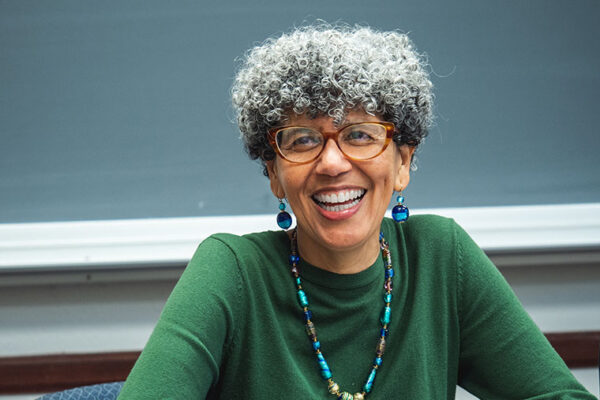

Rhaisa Williams is assistant professor in the Performing Arts Department, and also teaches in the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Department, both in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. With Stacie McCormick of Texas Christian University, Williams is editing “Toni Morrison and Adaptation,” a special issue of College Literature: A Journal of Critical Literary Studies, to be released in summer 2020.