“Steve, this is Mark Wrighton. How would you like to come work with me?”

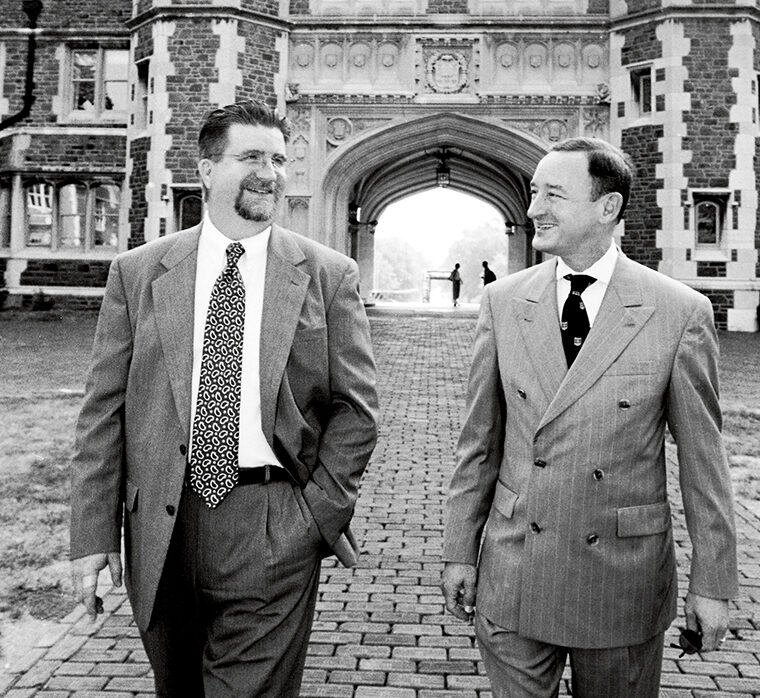

I will never forget that day in 1997 when I got the call from Chancellor Wrighton, following an exhaustive and exhausting interview process, asking me to come work for and with him as what was then called the assistant to the chancellor. I didn’t have to think for long.

“Yes, of course. When do I start?”

Since that day just a few years into his chancellorship, I have worked with him, totaling more than 20 years: the first nine as assistant to the chancellor and later as assistant vice chancellor. In 2007, I began a six-year stint as associate vice chancellor for public affairs, and I continued to work closely with Mark on issues related to the media and strategic communications. I returned to the chancellor’s office in 2013 as associate vice chancellor and chief of staff, knowing that he and I would both step down from our respective positions in four or five years. And here we are.

It has been the great professional honor of my life to work so closely with a leader of Mark Wrighton’s caliber and integrity for so long. The question that I get asked most often about my time with him is some version of, “What’s he really like?” My quick and ready answer is a bullet-point list of the things I most admire about him, beyond his myriad and well-known accomplishments for the university.

“He is the hardest-working person on campus with the longest hours. He is focused on the most important things and deftly sets priorities for himself and the university.”

— Steve Givens

He is, of course, brilliant. He is exceedingly kind. He has a photographic memory. He is the hardest-working person on campus with the longest hours. He is focused on the most important things and deftly sets priorities for himself and the university. He really cares about the people with whom he works and respects that they have personal lives. He will go to great lengths to help others succeed. He has a quiet, wonderful sense of humor.

And I usually end with this one, just so I can see the look on the questioner’s face when I say: “And, as far as I know, he’s never missed a day of work in 24 years, and I’ve never seen him sick.” Given his nearly endless travel schedule, much of it international, it’s nearly inconceivable that he doesn’t routinely return home sick. But nothing slows Mark down.

We are different people in so many ways. He was a world-renowned scientist (a MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient by age 34); I’m a kid who grew up in North St. Louis in the 1960s, who eventually made my way into the creative and administrative realms of higher education via an English degree. And, yet, we became a collaborative team and trusted colleagues, perhaps because of those very different but complementary skills and backgrounds.

Together, we have kept the Office of the Chancellor up and running (thanks to a wonderful team that requires very little management). And, along the way, we planned and celebrated some very special moments, including our sesquicentennial year in 2003–04 and four internationally televised debates under the aegis of the Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD).

As we both prepare to leave the suite in North Brookings — Mark into further service to the university and me into a life of writing, retreat and workshop facilitation (and occasional consulting for the CPD) — I find myself reflecting on what I have learned from my time working so closely with a man who is undoubtedly one of the greatest and most effective chancellors in the history of Washington University and in America today. And I keep coming back to two things.

“Passion is required for the job of chancellor, but so is compassion. Mark Wrighton has deep stores of both.”

— Steve Givens

First: You don’t need to shout to be heard and respected. I have never seen Mark lose his cool or heard him raise his voice in anger or frustration. Did he have tough conversations that didn’t end well? Of course. Did he need to correct, reprimand and even terminate? Yes. But he never did those things in a manner that was anything other than controlled, humane and respectful to the other person. Passion is required for the job of chancellor, but so is compassion. Mark Wrighton has deep stores of both.

Second: You can respond only to the opportunities you have. Or, as he for so many years told the incoming class of first-year students at convocation, quoting Louis Pasteur, “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

For Mark, Pasteur’s wisdom is not a call to sit back and wait for opportunities. Rather, it’s about getting up every morning knowing the very best you can

do is give other people chances. For him, that has meant embracing the early Latin definition of chancellor: the doorkeeper.

Mark Wrighton’s job has been to open doors for others — students, faculty, staff and alumni. Every member has him to thank for the 21st-century institution that is now better prepared to educate and position them for careers, nurture their academic passions, empower them to solve problems, and more creatively reflect and communicate the intricacies of the world.

The doors of Washington University are open more widely than ever before, making a world-class university education more accessible to all who have worked hard and are ready for their chance. Mark Wrighton showed me that it’s a privilege to empower others.