In the late ’60s, Jonathan Weaver, BSBA ’72, left his home in Rockville, Maryland, and flew nearly 800 miles across the United States to Washington University. He was one of only a handful of black students in his undergraduate class. This was not new to him. Though he’d grown up in a black neighborhood, his high school had been predominantly white. His mother, who taught English at his school, had been the first black teacher in a classical subject. He thought he was prepared. That was until he met his roommate in his Liggett dorm room.

“You left your washcloth in the bathroom, boy,” Weaver’s roommate said to him one day.

“I was so angry,” Weaver recalls. “I did say to him, if I ever hear you say that again, we’re going to have more trouble than we have right now.” His roommate moved out a few weeks later. But black students across campus were having similar isolating experiences.

In class, you were often the only other black student there and faculty weren’t always allies. “Coming here and experiencing this environment was like stepping back into the south. And that wasn’t acceptable,” Robert Johnson, MA ’70, MA ’74, PhD ’76, BS ’84, said on a recent panel about the time period.

Previously, Johnson had been an undergraduate at Lincoln University, a historically black college whose notable alums include Thurgood Marshall. He was coming to a university that aligned itself decidedly with the South in 1947 when President Truman’s Commission on Higher Education called for the repeal of state laws requiring segregation in education. Then-chancellor Arthur Holly Compton, along with three southern institutions, advocated for inequalities to be removed gradually, “within the established patterns of social relationships.”

The folks in ABC “became family. They became home. They became your support system. And they helped to build your intellectual depth and curiosity.”

Sharon Butler

While most graduate programs at WashU (except dentistry) were desegregated by 1949, the first undergraduates weren’t admitted until 1952 and then in puny numbers. The dormitories remained segregated until 1954.

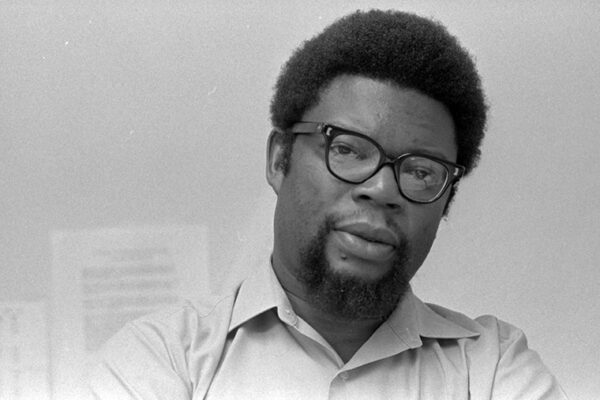

Johnson was admitted in 1967 as part of the Consortium for Graduate Study in Business for Negroes, which aimed to increase WashU’s black student population and help more African-Americans get into management positions at large companies. Johnson’s cohort, the first, had seven students at Washington University and 14 others studying at other universities. “There was lots of outright hostility from the faculty, some callousness, some indifference, and a few who were receptive and supportive,” Johnson remembers.

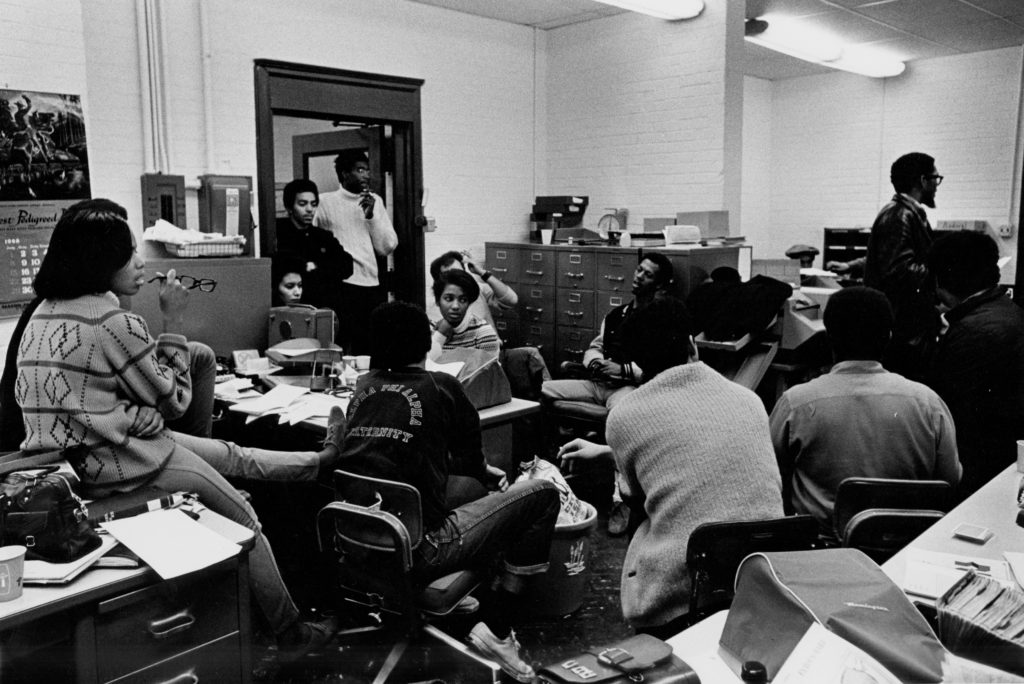

Johnson arrived in September. By October, he and about 30 others had formed the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) (later to become the Association of Black Students (ABS)). Johnson became the association’s president. The group’s main focus was to organize black students on campus, address police harassment, and change the negative portrayal of blacks in the curriculum. ABC also made connections with local civil rights organizations, helped each other academically, and met with black students from other predominately white campuses in the St. Louis area to help them form black student groups. Johnson remembers the group befriended black employees who worked in food service, cleaning service and groundskeeping.

“Many hourly wage employees confided in us about their working situations and the official and unofficial policies and practices under which they were working,” Johnson says. “Many [practices] were blatantly unfair, racist, sexist and exploitive.”

ABC wasn’t all about politics though. Oliver Green, MA ’70, who helped Johnson start the organization, emphasizes how it grew out of camaraderie. He already ate and played cards with fellow ABC members in Bear’s Den. Students simply met more formally as ABC on Sundays. There Green, Johnson and others would talk about meetings they’d had with the administration about improving life on campus. They also organized social events (ABC had an intramural team), created a tutoring program with the YMCA, and mentored local black teenagers.

Butler, who was also a founding member of ABC, agrees, “The people became family. They became home. They became your support system. And they helped to build your intellectual depth and curiosity.”

In the fall of 1968, ABC invited new students to join, voted in new officers (retaining Johnson as president) and resumed discussions with the administration. “We were caught up in a web of committees and meetings to discuss matters with the administration,” Johnson says. “Change on many issues was slow, drawn out or not very promising.”

The Protest Begins

Then on Dec. 5, 1968, Elbert Walton, MBA ’70, a member of the second cohort in the business school’s consortium for Negroes, had a run-in with campus police. Around 10:30 a.m., he was stopped and refused to show police his license. He was then allegedly forced to the ground, handcuffed, kicked and thrown into a police car. He was later pushed into a chair while cuffed at the police station.

Black students across campus were regularly harassed by police. Johnson had been stopped three times in the last year, including once while entering a dorm elevator. In one interaction, the campus police called William B. Pollard, AB ’70, boy. When he protested, the officer responded, “I’ll call you any goddamn thing I want, boy.” Pollard asked for his name, only to later discover that the officer provided a fake one.

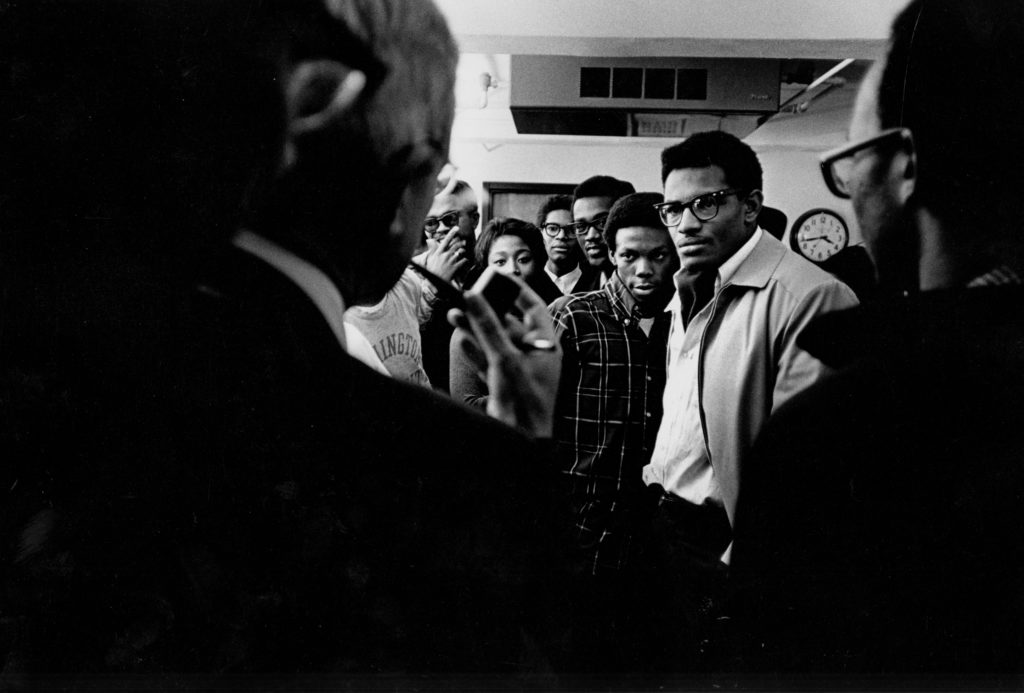

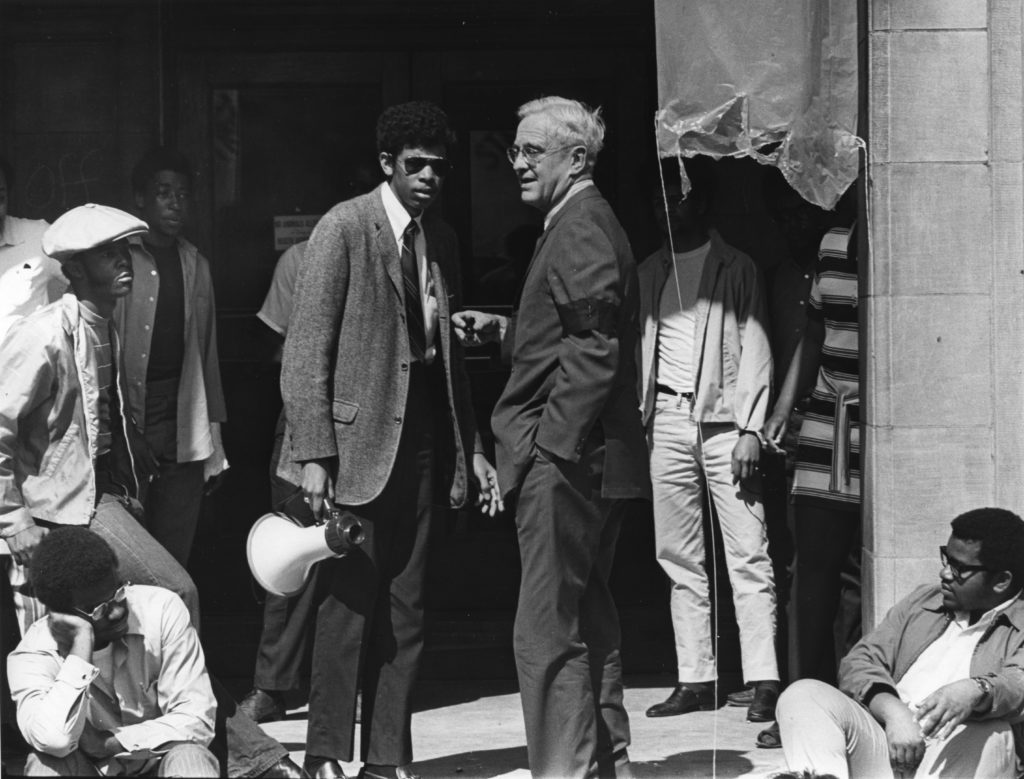

So when word spread about what happened to Walton, “we decided we would approach the police station,” Johnson says. “They weren’t very responsive, so we told them we were going to be there until they were more forthcoming in their responses.”

Police left the 15-square-foot office in Busch Hall, which rapidly filled with more than 30 protesting students. Suddenly, Johnson was spearheading a sit-in.

Less than an hour in, Chancellor Thomas H. Eliot arrived with Vice Chancellor Carl Dauten and Assistant Vice Chancellor John Whitley. Smoking his pipe, Eliot listened to the concerns from Johnson and the rest of ABC.

Johnson said they wanted the police officers fired, but Eliot said that they would have to have a hearing. He scheduled it for a few days later, but the members of ABC at least wanted the officers to have to turn in their badges. Eliot refused, so ABC refused to leave.

The night wore on, and various administrators came by to ask the students to leave. A university staffer harangued the students, shouting at them from outside of the police station, “Why are you doing this? What do you want to accomplish?”

A nearby group of students in lettermen jackets joined in. “Let’s get them out of there! C’mon, join me! They don’t belong there!” Tensions mounted, but eventually, everyone left before there was an altercation.

While black students were holding onto the police station, a group of white protestors decided to move up the date of their anti-ROTC demonstration to that evening. Twenty-five students planned to seize the rifle range on the third floor of Cupples II.

“Our restraint is taxed.”

Robert Johnson

Thwarted by a locked door, the students moved on to North Brookings, where they invaded the chancellor’s office. Despite it being 8:45 p.m., the chancellor and his staff were still there, due to concerns about the protest at the police station.

The evening fell apart from there. Several white students threatened a counter-protest to get the protest out of Brookings, the lights in North Brookings were cut off, and a student still trying to break into the rifle range got arrested.

While the white protesters expressed solidarity with ABC, on Friday morning the two groups scheduled press conferences for the same time. At his, Johnson issued a position paper, stating that before ABC would negotiate, the university had to fire the police officers involved in the altercation with Walton.

“Our restraint is taxed,” Johnson said.

Then, he and four others went over to Brookings to request that everyone leave. The white protestors did not take kindly to the suggestion. The attitude was “we won’t let those black students tell us what to do,” an eye witness said.

Johnson decided to move ABC to Brookings too. ABC would occupy the basement while the anti-ROTC protestors occupied the chancellor’s office. “We strategically situated ourselves there so that we’d be less vulnerable to some of the outside attacks,” Johnson says. Plus, they were occupying accounts payable, which they figured was a place critical to the functioning of the university.

Arts and Sciences faculty got involved in the crisis Friday afternoon before a scheduled faculty meeting that would fill Graham Chapel and last until 2 a.m. They convened to discuss demands from both protests. The majority of the time was spent trying to terminate the ROTC program. (And, indeed, this was the meeting where liberal arts faculty voted to withdraw credit from ROTC courses.) But faculty also voted to endorse creating a black studies program and in support of the spirit of the demands of the protesting black students.

Gail Grant, AB ’72, daughter of David M. Grant, a prominent civil rights lawyer, was in ABC. The group reached out to her father to represent Walton at the hearing. In 1945, Grant had sued Washington University on behalf of four black students who were refused admission to the summer school. The lawsuit helped push the school to desegregate. Despite this, or maybe because of it, he wanted to get his daughter out of the protest.

When he told her to come with him, Gail hesitated a moment, but said no with the help of a fellow student.

“He gave us both a stern look and walked away, crestfallen,” Gail recalls. “I knew where I had to be and so did he.”

Back in his Liggett dorm room, Weaver was having a similar debate. He wanted to join the protest but kept imagining his mother’s objections. “On the third day, I just came to the realization that I could no longer go to sleep in that dormitory when there were a number of black students trying to deal with the inequities on the campus,” he says. “So I pulled myself together, walked to the administration building and knocked on the door.”

He remembers Green answering. “This is where I’m supposed to be,” Weaver said. Green let him in.

The hearing

After the hectic faculty meeting on Friday, most of the demands of the white students had been met, and they agreed to call a moratorium on their demonstrations by Sunday.

For Rob Johnson and ABC, the protest was nowhere near concluding.

The hearing on Monday, Dec. 9, ended up not being about the incident involving Elbert Walton. Instead, students who felt the campus police had harassed them were able to share their stories to a packed courtroom in January Hall.

Attorney David Grant accused the police of having assumed a “harassing stance” toward black students on campus. Eleven students shared stories of harassment; Gilbert Chandler, for example, said that black high school students that he had invited to Bear’s Den were told “they’d better watch themselves” by campus police.

The counsel for the university countered that these incidents had never been reported, and university administrators explained the rules for what happens when a student issues a complaint. It turned out that the rules weren’t even being followed. William Pollard had filed a complaint about the officer who called him boy, but the head of campus police hadn’t reprimanded that officer or put the complaint in his file.

The hearing concluded, and there was no additional hearing scheduled to address the incident with Walton. So black students continued their occupation of Brookings.

‘The Black Manifesto’

Two days after the hearing, ABC released “The Black Manifesto,” which was subtitled, “We must struggle to learn … and learn to struggle!” The 26-page document outlined the 10 demands the association had.

Creating the manifesto was a group effort, Johnson says. “We had some groups of people writing materials, some on research, and then we would edit the material.” The group got it typed up and were ready to present it when the document disappeared.

Johnson and the team had handed it over to someone who claimed he worked in a duplication center. “He took it for a long time,” Johnson says. “We discovered later that he was an undercover agent. He was a federal marshal or something.”

According to Johnson, the agent, who was black, had been hanging out with members of ABC on the South 40 for weeks. They didn’t learn he was an agent until later, when he dropped his wallet containing his badge in the restroom and some teens found it and brought it to Johnson. Now revealed, the officer never showed up again.

Whatever he did with the document while he had it didn’t matter. Johnson and the rest of ABC gave it to the administration and the press, and it became the guiding document for the Association of Black Students.

The manifesto explains ABC’s position. “Realizing that the needs and the problems of Black people on this campus are not being met, just as Black people suffer nationally and locally; realizing that the status quo hampers, impedes, destroys and is seriously detrimental to the best interests of Black people (and therefore to the best interest of the larger society), we call for significant changes within the university. Conditions cry out for new priorities to be established, for new standards raised and for old barriers to come tumbling down.”

By Saturday, Dec. 14, the administration and ABC had reached general agreement on six of the 10 points raised. The university agreed to (1) implement a black studies program, (2) provide more awareness and sensitivity training for staff around black student issues, (3) give black students a fully equipped meeting area, (4) provide assistance to blacks in finding off-campus housing, (5) eliminate its offensive African-American history course, and (6) grant amnesty to all the students who participated in the protest.

Four points were left open: (1) creating a policy for employment and promotion of black workers, particularly those working as porters, maids, or in food service or grounds keeping, (2) increasing financial aid for blacks, (3) increasing black enrollment (ABC’s goal was for the university to be 25 percent black by 1969), (4) ending university research in black communities.

Chancellor Eliot did agree to increase black enrollment to 8 percent the following year. The rest, he was open to discussing, though the demands as stated by ABC couldn’t be met. Johnson and ABC agreed to the terms and by 3 in the afternoon on Saturday had packed up their stuff and were leaving the accounts payable office in Brookings. One reporter noted that they left the office clean and neat.

Monday, Dec. 16, there was a second hearing: this one about what happened to Walton. The panel eventually cleared the officers involved of all charges, though the campus police director later resigned.

The aftermath

Still, things on campus did change. Johnson points out that ABS is the only student organization that has a permanent representative on the Board of Trustees. The university started an African and African-American studies program in 1968, but it took until 2017 for it to become a full-fledged department. When he graduated in 1970, William Pollard, a leader in ABC, gave the student address at Commencement.

After he graduated, Green was tapped to be director of an educational opportunity program at the university that helped underserved students by providing counseling and tutoring.

“The university responded [to our demands], saying you folks are going to have to help us, because we don’t know how to do this,” Green says. “It was a victory, if you will, but the war was not over.”

“It’s not like someone turned on a light switch and everything was done,” Pollard agrees. “Compared to today, 50 years later, it’s night and day. You really have to look at what the process was over time.”

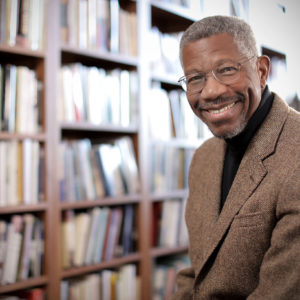

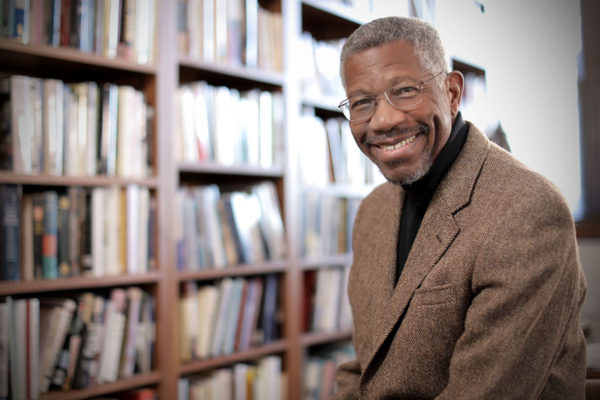

Pollard attributes James McLeod’s arrival on campus in 1974 to the Brookings sit-in. McLeod quickly became one of the few blacks in a leadership position at the university as assistant dean of the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. He went on to be vice chancellor for students and dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. With the backing of Chancellor Emeritus William H. Danforth, McLeod established the John B. Ervin Scholars Program in 1988. It gave bright African-American students full tuition scholarships and provided them with mentorship and counseling throughout their time here. The program was eventually opened up to any student with a commitment to community service.

For Weaver, the sit-in was a transformative experience. He went on to become president of ABS; sit on the Board of Trustees as a student rep; travel to Africa; and start an organization called the Collective Empowerment Group, which helps blacks get bank loans.

“ABS was an extremely tight-knit organization that really was looking to make a difference in the lives of black students on campus,” Weaver says. “And it energized me in terms of my own future to recognize that there was so much more that could be done.”

In May 2018, the university honored the members of the 1968 Brookings sit-in with the Trailblazers Alumni Award, which celebrates contributions to campus and community from black alumni, faculty and staff.

“The impact of the sit-in and the 1968 ‘Black Manifesto’ was enormous as it set the foundation for future negotiations between black students and the university,” says Rudolph Clay, head of Diversity Initiatives and Outreach Services at Olin Library. He also sits on the selection committee for the Trailblazers award. “Additional Black Manifestos were issued in 1978, 1983, and 1998, each document again bringing to the attention of the internal and external community the need to complete the goals originally proposed in 1968.”

Jasmine Pickens, the current president of ABS and a class of 2019 Arts & Sciences undergraduate, got to spend time with Johnson, Green, Weaver and others when they returned to campus.

“I can’t even describe how amazing this experience was,” Pickens says. “It was surreal to hear them talk about WashU and the experiences they had here — both good and bad. It was extremely powerful to be in their presence and experience the wisdom that they had to share.”

But she says the university also still has more work to do.

“Black staff are still routinely underpaid and overworked.”

Jasmine Pickens

“Black staff are still routinely underpaid and overworked,” she says. “There have been strides towards progress, but they are not enough to ensure that someone working 40 hours a week at one of the wealthiest universities in the world does not end up in poverty.”

The community around WashU also has some work to do. This summer, 10 freshmen were stopped by Clayton police after dining at IHOP, despite not matching the description of the party that had been reported for theft of services. The students, many of whom could present receipts, were made to walk back to IHOP, where Management verified that the police had the wrong people. The university administration had several meetings with the city of Clayton and let the students and their parents speak directly to city officials.

Toward the end of a statement, Clayton City Manager Craig Owens wrote: “We will close by just sharing how extremely impressed we are by these Washington University students. We are grateful that they have been willing to share their experience and their perspective. They came to Washington University to change the world and they have already done so.” Owens says that the Clayton police force will increase its training in diversity issues and start using body cams.

But black students on campus do have reason to celebrate. In the spring the university gave black students House 5 (former fraternity house for Phi Delta Theta, which was permanently suspended from campus). The 30-bed house fulfills one demand that ABC had advocated for, dedicated black student housing.

So there’s reason to celebrate and keep fighting. For Oliver Green, that’s part and parcel of activism. “When you’re marching, you march,” he says. “You can’t sit back on your laurels and say, ‘wow, we did a great job.’ No, you don’t have time for that. You just have to keep on moving.”