This year, Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein turns 200. Washington University is celebrating the bicentennial with special events, conferences, film screenings and more. One of the organizers, Corinna Treitel, associate professor of history, is most excited about the conversations Frankenstein can spark.

“I thought celebrating the bicentennial would be a really great opportunity for a university like ours to create conversations between people who don’t normally talk to each other,” Treitel says. “The novel is often drawn into discussions about science and social responsibility, but it’s also a foundational text for thinking about otherness.”

Medical ethics are at the crux of the novel’s central story about Victor Frankenstein, a college student who decides to reanimate dead tissue. When he is successful, Frankenstein is horrified by what he has created and abandons his creature.

The creature is a quintessential “other.” Despite not having parents, he teaches himself language and civility, but people are so horrified by his appearance that their first response is to run away or try to kill him. The creature becomes an outcast and a murderer, determined to destroy his creator’s life.

“The novel is really about failure of inclusion,” Treitel says.

“[Shelley] created an outsider figure that can be read onto lots of different marginalized groups,” adds Amy Pawl, senior lecturer in English, who along with Treitel created and taught the interdisciplinary course “Frankenstein: Origins and Afterlives” in fall 2017. “The novel raises questions of sympathy for that outsider creature and the responsibility that the dominant culture needs to take for creating these awful positions for people to exist in,” Pawl says.

This topic of identity and inclusion was among the reasons the novel was selected for WashU’s 2017 Common Reading Program. All first-year students were asked to read the book and discuss it at the beginning of the 2017 fall semester.

In small groups, students used the novel to discuss current events, identity politics and the background of the young author. (Mary Shelley famously wrote Frankenstein as a teenager after she’d run off with and gotten pregnant by the renowned — and married — poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.) The book also served as a jumping-off point for a one-credit identity-literacy class offered to first-year students.

This year, students are competing to create a new Frankenstein for the modern age. Treitel and the Center for the Humanities are sponsoring a competition, in which students can write or create an art piece that reimagines the classic tale.

Treitel also organized a conference in October 2017, “Frankenstein at 200,” that dealt with the novel and its “afterlives” in popular culture. The daylong event included three panels that discussed how Frankenstein has been retold through the African-American experience, how the monster inspired the creation of disability studies, and how the novel is still shaping art today, among other topics.

“Historians are always interested in change over time,” Treitel says. “This is a novel that has been drawn into conversations in very different kinds of ways over the past 200 years. I thought it would be interesting to see how scholars across a variety of disciplines were talking about Frankenstein right now.”

Another conference, “The Curren(t)cy of Frankenstein,” will be held Sept. 28–30, 2018, at the School of Medicine. Organized by Rebecca Messbarger — director of the Medical Humanities program and professor of Italian, history, art history, and women, gender and sexuality studies — this conference will focus specifically on the novel’s relevance for contemporary medical practice.

One speaker will be Luke Dittrich, who wrote the award-winning book, Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets, about the rise of the lobotomy. Part of the book is about Dittrich coming to terms with the fact that his own grandfather performed the controversial procedure on countless patients.

“Dittrich’s talk will be about the power of medical and scientific innovation. But like Frankenstein, it will raise questions about the responsibilities and the ethics that must undergird that same innovation,” Messbarger says.

The three-day event will also feature a Frankenstein performance piece, a demonstration of alchemical experiments and a panel of experts from the sciences and the humanities on the meaning of the novel for medicine today.

The issue of science and ethics is perhaps even more pressing today than in Shelley’s time. This September, Jennifer Doudna, a professor of chemistry as well as of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, will talk about the technology she helped create, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, which allows scientists to manipulate genes. A powerful tool in curing disease, it also raises questions about ethics. Worried about what editing the human genome could mean, Doudna called for a moratorium on the clinical use of gene editing in 2015.

Although science can’t reanimate dead tissue as Frankenstein did, human beings are moving ever closer to the intelligent design previously ascribed only to the gods. As Nick Dear, the playwright who recently staged Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in London, said when he came to campus Sept. 6, 2017: “Mary Shelley was writing, almost without appreciating it, a creation myth for the science age. [Creating the monster] involves solely the skills of humankind. And that’s why I think it stays with us now, because God doesn’t play a very big part in our rationalization about the world we live in.”

Treitel saw the questions that this creation story raised as extremely pertinent when she read it as an undergraduate studying chemistry, the same field that Frankenstein studied.

“The questions [the novel] made me ask concerned the vexed relations of science and society,” Treitel wrote in an article about the bicentennial. “Should scientists dare to alter living matter? I knew, of course, that the question was moot: They dare; they do. But more questions followed: How do we do such research ethically? What are our responsibilities to the organisms produced? Who should be involved in asking and answering such questions?”

The Frankenstein bicentennial won’t, of course, answer all of these questions, but the novel is still a useful tool in making us ask the tough questions about ourselves, our ethics and our future.

For more information visit Frankenstein200 and Frankenstein 200 on The Source.

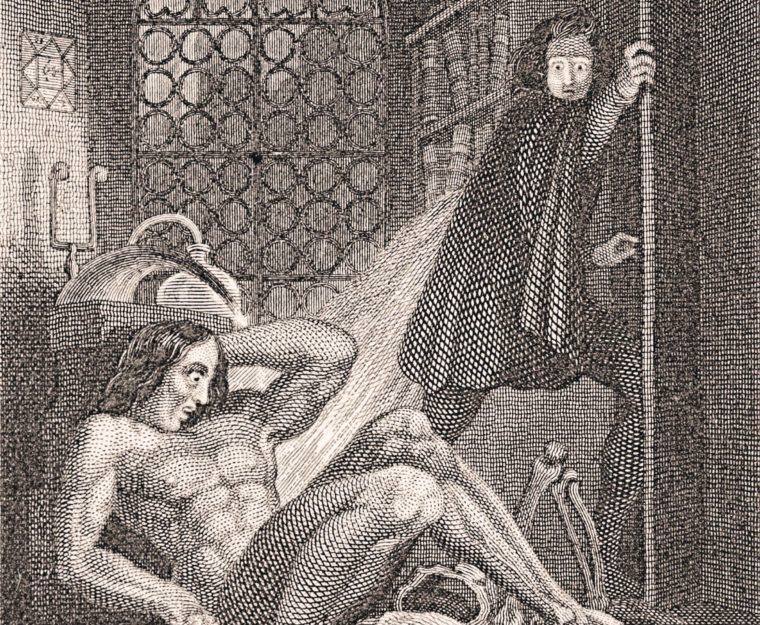

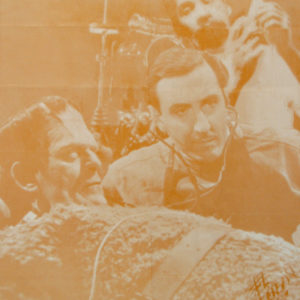

The Kemper Art Museum hosted an art exhibit of images related to Frankenstein in October 2017. Below are images from the exhibition.