For 30 years, Ervin Scholars at Washington University in St. Louis have come together for class dinners, winter retreats, service projects and all-class reunions.

But a new tradition emerged recently — the celebration of yet another Ervin Scholar to be named a Rhodes Scholar, one of the world’s most prestigious and competitive academic honors.

Since 2010, every Washington University Rhodes Scholar has also been selected as an Ervin Scholar, including Joshua Aiken, AB ’14, who won in fall 2013; and Priya Mallika Sury,* AB ’10, who was awarded the Rhodes in fall 2010. In fall 2017, two Ervin Scholars (just the second time two WashU students were selected for the award in the same year) — seniors Camille “Mimi” Borders and Jasmine Brown — won the scholarship. [*While a WashU student, Priya Mallika Sury, AB ’10, who was awarded the Rhodes Scholarship in fall 2010, had been selected for a Danforth, Ervin and Rodriguez scholarship. Being able to choose only two of the three, she chose the Danforth and the Rodriguez.]

“Josh [Aiken] was one of the first people to congratulate us,” says Borders, sitting next to Brown before a television interview. “I can still remember him speaking to us at our Ervin orientation. I was so impressed by all that he’d already achieved.”

“Me, too,” Brown adds. “I always thought that ‘changing the world’ was something I’d try to do after I was grown up with a career and money. But listening to him, I realized I didn’t have to wait. I could make an impact now.”

In addition to the winners, Ervin Scholar Damari Croswell, AB ’15, was a Rhodes finalist in 2016. He is now at Harvard Medical School. And Nicholas Okafor, BS ’16, a mechanical engineering and materials science graduate, was a finalist in 2016. Okafor currently works in Kenya for Burn Manufacturing, which designs fuel-efficient cooking products that save lives and forests in the developing world.

Robyn S. Hadley, associate vice chancellor for student affairs and dean of the Ervin Scholars Program, is a Rhodes Scholar herself. And she is not surprised that so many Ervins have wowed the Rhodes selection committee.

“Both programs are looking for true scholars who want to answer the big questions — and have already demonstrated a deep commitment to improving the world around them,” Hadley says. “That is most certainly the case with Mimi and Jasmine, two incredibly smart and humble individuals.”

Brown, a biology major in Arts & Sciences, has served as a research assistant at some of the nation’s top institutions, including the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Currently, she is working at the Washington University School of Medicine to uncover the molecular pathways that West Nile and Zika viruses travel to infect the brain. She plans to obtain a doctorate in neuroscience at Oxford University.

Brown also founded the Minority Association of Rising Scientists (MARS) to support underrepresented students and to educate faculty members about implicit bias. She has been working with the National Science Foundation to expand the program nationally.

Borders, a history major in Arts & Sciences, helped create the group Washington University Students in Solidarity in the aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson in 2014. As a campus leader, she facilitated dialogues about race and successfully advocated for changes at Washington University. Meanwhile, she distinguished herself as a scholar: serving as a research assistant on the oral history project “Documenting Ferguson,” working on independent historical research since her sophomore year as a Mellon Mays Fellow, and studying the transatlantic slave trade at the Fulbright University of Bristol Summer Institute. At Oxford, Borders plans to pursue a master of philosophy degree in social and economic history.

“To be an Ervin has been to be part of a family — a really nurturing, really motivating family.”

— Mimi Borders

Borders and Brown, who are Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority sisters and “besties,” say their friendship sustained them during the arduous Rhodes application process. But they credit Dean Hadley and their Ervin peers for their success.

“I can’t describe the way they have changed my life and taught me to keep pushing,” Borders says. “To be an Ervin has been to be part of a family — a really nurturing, really motivating family.”

‘Am I doing enough? Can I do a bit more?’

Being a part of the supportive Ervin family lasts a lifetime, too. Last fall, for example, more than 500 members reunited at the university to commemorate the program’s 30th anniversary. Ervin alumni remembered the legacy of the program’s founder, the late James McLeod, vice chancellor for students and dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. They also paid their respects to Jane Ervin, the widow of program namesake John Ervin, the university’s first black dean; and to Clara McLeod, the widow of James McLeod and earth and planetary sciences librarian at WashU. Further, alumni reflected on the ways the Ervin experience continues to define who they are today.

Alumnus Fernando Cutz, AB ’10, who was promoted to senior adviser to U.S. National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster in October 2017, shared with current Ervin Scholars how the scholarship set him on a path of public service.

“The Ervin program is fundamental to who I have become,” Cutz says. “It’s an incredible community because it pushes you. You get to see all of these accomplished individuals fighting for causes you believe in. It makes you look at yourself and say, ‘Am I doing enough? Can I do a bit more?’”

As a student, Cutz served as senior class president and waged a successful campaign against the Chicago bar that discriminated against black students during their senior trip. Cutz also started WU/FUSED, a student group that fought successfully to increase the number of Pell-eligible students on campus. The organization currently has some 25 chapters at colleges across the nation.

Formerly director for South America at the National Security Council, Cutz now works on issues relating to the entire world. The work is exhausting but invigorating, he says.

“I will walk into the White House thinking I know what the day will bring, and an hour or two later, the day shifts completely,” Cutz says. “Every day, I take a moment to think about the people who came before and the decisions they made — good and bad — that affected national security and foreign policy. I know one day people will examine my decisions, and that motivates me to do my very best for my country.”

Jason Green, AB ’03, is another senior class president turned White House staffer. As a student at Yale Law School, Green joined the presidential campaign of Barack Obama, managing field operations and get-out-the-vote efforts. After earning his law degree, he worked four years as President Obama’s associate counsel and senior adviser.

Today, Green is working on multiple projects. He helped found The Arena, a nonprofit that develops and trains the next generation of civic leaders, and launched SkillSmart, a platform that pairs employers with job seekers with the right skill sets and experiences. Green also is producing a documentary about three segregated churches, including his grandmother’s church, that came together in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

“All of these things are about building community,” Green says. “And that all starts with really knowing someone, as Dean McLeod would say, ‘by name and by story.’”

Turning classmates into a community

Today, the Ervin Scholars Program is lauded as one of Washington University’s most prestigious programs. But it was born out the university’s difficult history. Back in 1986, only 36 black students enrolled as freshmen at Washington University. Then-Chancellor William H. Danforth turned to Dean McLeod to find a fresh way to draw more black students.

McLeod acted fast, creating a program that would provide 11 full-tuition, merit-based scholarships to talented black students each academic year. The initiative was an immediate success, attracting more than 300 gifted applicants in 1987.

But McLeod recognized at once that the program could do more than draw students; it could also develop leaders. One by one, he introduced new programs that became signature traditions: monthly class dinners, fall orientation and a winter retreat. These events encouraged classmates to become a community.

McLeod was supported by Dorothy Elliott, assistant director of the Ervin Scholars Program; the late Adrienne Glore, assistant dean of students; and, of course, John B. Ervin himself. Admired across campus for his commitment to justice and his kindness to students, Ervin interviewed applicants and participated in programs. In A Legacy of Excellence — a history of the program’s first 20 years written by Ervin alumna Monica Lewis, AB ’99 — Elliott recalled receiving word of Ervin’s death hours before he was to meet the new Ervin class in 1992.

“Jane called at about five in the morning. She said the last thing she saw John do before she went to bed was look over the Ervin folders so he could really knock their socks off when he met them. He told her to go to bed. The last thing he did was look at those folders,” Elliott shared with Lewis for the historical account.

“Not only did the Ervin Scholars Program build a foundation and draw better and better and more and more African Americans, it also helped catalyze the African-American presence in events, activities and organizations.”

— Paul Wright

Further, Paul Wright, AB ’91, a member of the inaugural class of Ervin Scholars, told Lewis that the program immediately changed the campus climate.

“Not only did the Ervin Scholars Program build a foundation and draw better and better and more and more African Americans, it also helped catalyze the African-American presence in events, activities and organizations,” Wright said. “There were more of us, but people were also doing more. It was really something that was noticeable by contrast in three or four years.”

“White students — and faculty — also benefited,” said Sharon Stahl, vice chancellor of students emerita.

“Students who come here and succeed in the classroom and the laboratory and assume roles of leadership in the community have helped our majority students and faculty to cast away the stereotypes that unfortunately still linger in our society,” Stahl recalled for the written history. “It’s not their responsibility, but they’ve been able to do it. And because of this ‘educational’ side effect, our majority students graduate going into the world better able to be informed citizens in the workplace, appreciative of the contributions and abilities of their African-American co-workers.”

Helping people grow together

The program was threatened in 2003 when the Supreme Court ruled race-exclusive admission policies unconstitutional. University leaders disagreed with the court, but ultimately they changed the program’s admission requirements. Candidates, university leaders determined, need not be black, but they must demonstrate a commitment to diversity, service, academic excellence and leadership.

ShaAvhrée Buckman-Garner, AB ’92, MD ’99, PhD ’99, FAAP, a member of the second Ervin cohort, says today’s students are being prepared to share Ervin values with their future workplaces and neighborhoods. A quintessential scholar herself, Buckman-Garner is director of the Office of Translational Sciences in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, where she oversees the work of some 600 employees. She joined Cutz, Green and Blavity founder Morgan DeBaun, AB ’12, at a fall 2017 Assembly Series panel, “Measuring the Impact and Influence of Ervin Scholars.”

“We are all from a variety of backgrounds — different ethnicities, different socioeconomic classes — in a program that promotes family,” Buckman-Garner says. “That helps us look at that person who is your brother or sister in a new way. And you realize that that person you perhaps thought of as an ‘other’ has more in common with you than you anticipated. When you look at our long-range goals as a society, you have to put people in an environment where they can grow together.”

Another profound change to the program came in 2011 with the death of McLeod — a loss to both Ervin Scholars and the entire university community.

“Working with Dean McLeod was one of the great honors of my life, and that says a lot after serving two presidents,” Cutz says. “Dean McLeod had this wisdom, this patience, this understanding. I frequently ask myself: ‘Who are you? Where do you come from? Where are you going? What do you stand for?’ These are the guiding principles that Dean McLeod instilled in me.”

‘I have felt incredibly cared for’

Today’s Ervin Scholars hold the same values. Before arriving as first-year students, all Ervins must read McLeod’s Habits of Achievement, the printed version of McLeod’s orientation lecture; Lewis’ history, A Legacy of Excellence; and A Legacy of Commitment, by Ervin Scholar Michelle Purdy, AB ’01, MA ’03, who earned a doctorate from Emory University and is now an assistant professor of education in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.

“I ask a lot of questions. … I would like to think these conversations are an opportunity for a student to pivot away from the gen-chem homework or the anthro test and to dream big.”

— Robyn Hadley

As dean, Robyn Hadley brings her own ideals to the program. In addition to being awarded the Rhodes, Hadley received the University of North Carolina’s famed Morehead-Cain Scholarship, the first merit scholarship in America. She counts the program’s late leader, Mebane Pritchett, as one of the two most important role models in her life. The other: her mother.

“Mebane Pritchett helped me see my potential as my future, and his interactions with me inspired how I approach this work today,” Hadley says. “Like him, I ask a lot of questions. I encourage our students to be open, to be vulnerable and to dive deep. I would like to think these conversations are an opportunity for a student to pivot away from the gen-chem homework or the anthro test and to dream big. ‘You want to travel to Kathmandu? Okay, what will it take to get there?’”

It was during one of these talks that Hadley convinced Grace Egbo, then a first-year student, to apply for a competitive internship at Facebook.

“When I first found out about the opportunity, I didn’t know what to do,” recalls Egbo, now a junior studying computer science in the School of Engineering & Applied Science. “Dean Hadley convinced me that I should take my shot. Her encouragement got me to take a step I wasn’t sure I was ready for, and I got it!”

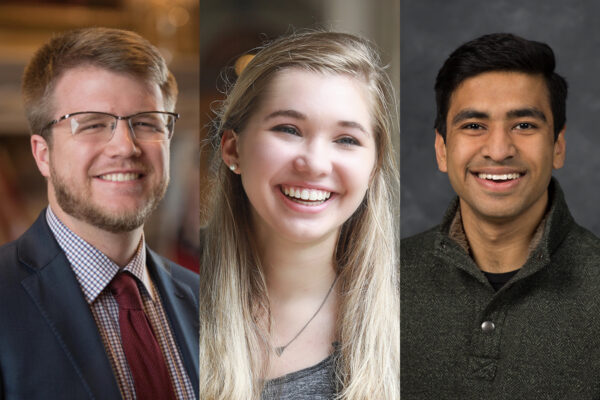

Hadley is supported by staff members Kristopher Campa, AB ’13, and Jonathan Williford, AB ’16, both alumni of the Ervin Scholars Program. Current Ervin Scholar Sophia Kamanzi, a pre-med student in Arts & Sciences, says the Ervin team is why she chose to apply to Washington University. Hadley and Williford attended her high school’s senior night. And when Kamanzi left her backpack in a locked building, Williford calmed her down and provided advice on the steps she could take to retrieve it.

“That’s why I call Ervins my family. Your family helps you, not because they have to, but because they care about you and want the best for you.”

— Sophia Kamanzi

“I have felt incredibly cared for in the Ervin Scholars Program,” Kamanzi says.

Kamanzi looks forward to biweekly Ervin dinners, when students each share a high and a low from the past weeks.

“When I hear the highs, things I thought seemed out of reach feel doable,” she says. “But I also like hearing the lows, because, with everyone here being so talented, it’s easy to forget that everyone struggles. It’s good to hear the honest truth.”

Kamanzi says that older Ervin Scholars are quick to offer help and advice. “That’s why I call Ervins my family,” Kamanzi says. “Your family helps you, not because they have to, but because they care about you and want the best for you. It’s a great feeling knowing everyone is here for me. I just need to ask.”

Diane Toroian Keaggy, AB ’90, is senior news director of campus life.