It’s curious that we heard very little from the C-Suite in the deliberations leading up to the Dec. 22 signing of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. What makes this curious is that the goal of the act was to increase GDP growth above 3 percent by stimulating corporate investments to increase productivity, but no one seemed to be asking CEOs whether the tax cut would have that effect.

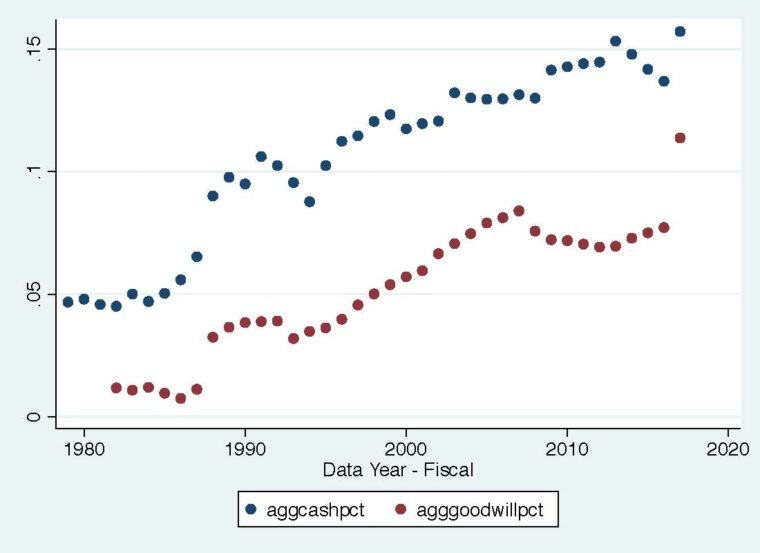

The fact that no CEOs were lobbying for the tax cut provides clues to the answer. But we can guess what they would have said, merely by looking at what they’ve been doing for the past several years. The record indicates that they will have little use for the cash windfall. Companies are already sitting on enormous amounts of cash for which they appear to have no use. Cash as a percentage of assets has increased from an average 4.5 percent in the 1980s to 15.7 percent last year (Figure 1 above).

The fact that no CEOs were lobbying for the tax cut provides clues to the answer. But we can guess what they would have said, merely by looking at what they’ve been doing for the past several years. The record indicates that they will have little use for the cash windfall. Companies are already sitting on enormous amounts of cash for which they appear to have no use. Cash as a percentage of assets has increased from an average 4.5 percent in the 1980s to 15.7 percent last year (Figure 1 above).

Moreover, those companies using their cash merely reallocated it: to shareholders (as dividends or stock buybacks), or to shareholders of other firms (as acquisitions). In fact, acquisitions have grown at the same rate as cash. We can track that, because acquisitions show up as “goodwill” on company balance sheets once they’re acquired. Goodwill has increased on average from 1 percent of assets through most of the 1980s, to 7 percent more recently, before experiencing a tremendous jump last year to 11.4 percent (also shown in Figure 1).

We can even take Apple, the poster child for the benefits from the Tax Act, as a prime example. While they may be repatriating $252 billion in overseas cash holdings, which would mean they will pay $38 billion in taxes that the United States would not have seen otherwise (enough money to fund the entire U.S. government budget for Science, Space, Technology and Energy for one year), they are not increasing investment. According to their Jan. 17 news release, Apple plans to invest $30 billion in capital spending in the U.S. over the next five years and create 20,000 jobs. While this sounds great, this represents a decrease in capital spending. Apple’s capital expenditures for the prior five years were $54.2 billion.

So why isn’t the tax cut stimulating more investment by Apple and other firms? The simple reason is that while the act removes incentives to conduct activities overseas, it does nothing to change the returns to investment. Investment and profits on investment are taxed at the same rate, so taxes are irrelevant to investment decisions. Accordingly, the tax overhaul should have no impact on productivity, and, as a result, can’t contribute to the goal of increasing economic growth above 3 percent.

In order for the tax cut to increase growth, firms needs to invest in real growth, rather than the acquisitive growth we have seen in recent years. This comes in the form of expanding into new markets, or increasing the value of things produced for those markets through Research & Development. R&D is the primary driver of company and economic growth. In fact, economic theory holds that the growth rate will double if the level of R&D doubles. The problem with that theory: It assumes company R&D productivity stays constant, but it hasn’t. Companies’ R&D productivity (measured as RQTM) has declined 65 percent on average since the 1980s. This means one dollar of R&D generates only one-third the growth it did in the 1980s.

Thus, increasing R&D won’t increase growth. In fact, two-thirds of companies are already overspending on R&D — meaning the last dollar they invest in R&D generates less than $1 of profits. Accordingly, the last thing we want those companies to do, is increase their R&D investment, an argument I made in a May 2012 Harvard Business Review article, “The Trillion Dollar R&D Fix.”

Why have firms become worse at R&D? My book “How Innovation Really Works” offers a number of explanations I explored as part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) funded study linking company R&D practices to their RQTM. However, the biggest explanation appears to be R&D outsourcing.

Rather than increasing their cash, what companies need to do is raise their RQTM, so they can productively use the cash they already have. That will create growth.

Anne Marie Knott, professor of strategy in the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis, researches the optimal environment and policies (economic, industrial and firm) for innovation. This interest stems from issues arising during an earlier career in defense electronics at Hughes Aircraft Company.