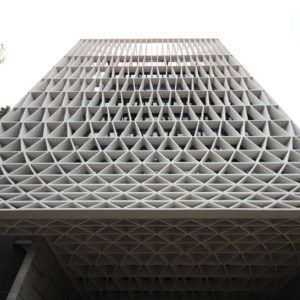

Erik L’Heureux, AB ’96, associate professor and undergraduate program director at the National University of Singapore, designs buildings that are sustainable works of art. His A Simple Factory Building, for instance, is not only beautiful but also helps mitigate environmental challenges. This is thanks to a stunning yet simple trellis that wraps around the building.

This facade, called an envelope, helps keep a building cool and protected from sun and the elements, which is especially important in a tropical climate like Singapore’s.

“The most fundamental thing that architecture does is change the climate between a too hot exterior and a cooler inside, or a cold outside and a warm inside,” L’Heureux says. “But that can require a tremendous amount of energy. If we think about design more carefully, we can produce more sustainable buildings, reduce our energy dependence and also produce more delightful variation in the architectural and urban spaces that we inhabit.”

The building won the 2013 World Architecture Festival Design Award as well as an American Institute of Architects New York Design Award. L’Heureux’s interest in sustainable architecture in tropical climates also won him the 2015 Wheelwright Prize from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

The prestigious prize is a $100,000 traveling fellowship. L’Heureux is in the process of traveling to Jakarta, Indonesia; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Pondicherry, India; Lagos, Nigeria; and São Paulo, Brazil — all dense cities located in the tropical zone.

“I’m looking at how the city is changing in relationship to density and demographic pressures,” L’Heureux says. “The issues of climate, especially in the hot and wet equator, are very different than in America. And this has a huge impact on architecture and the way urbanization happens.”

These cities are also some of the world’s fastest growing. The world population is projected to be around 9.7 billion by 2050. “That’s like adding two new Beijings every year for the next 34 years,” L’Heureux says. And that’s if just half of all those new people decide to live in cities.

L’Heureux has long been thinking about how design can solve problems. He came to Washington University to study architecture as a James W. Fitzgibbon Scholar. After graduating, L’Heureux went on to Princeton University where he earned his master’s in architecture. He then moved to New York, where he worked at firms including Perkins + Will and Agrest & Gandelsonas while teaching at the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at The Cooper Union.

“[Then] 9/11 happened,” L’Heureux says. “And the economy went south. And I thought maybe I needed some fresh air from New York.” He was offered a fellowship to teach at the National University of Singapore. And what was supposed to be a six-month stint turned into a long-term future. While in Singapore, L’Heureux became increasingly intrigued by the challenges of sustainable architecture in the tropics.

Now with his Wheelwright grant, L’Heureux — who considers himself both an architect and educator — hopes to develop new architectural and urban knowledge, relaying this back to his teaching pursuits.

“I think the challenges that we face in the world today are happening where the world is developing very fast and urbanization is happening at amazing speeds,” he says. “That’s more or less occurring on the equatorial belt.”

Population growth necessarily brings with it problems, but L’Heureux sees opportunity there too. “It’s a great moment,” he says, “especially for architects, urban designers and landscape architects to be involved in crafting our urban future.”