About halfway through a doctorate in molecular genetics at Washington University, Tina Saey began to realize that she didn’t really want to be at the bench anymore. “I was kind of bored in the lab,” she says.

“I realized later that I had been so excited by science because I was learning new things all the time, yet once I actually started my doctoral research, I was concerned with only one thing. And I had been doing that one thing for three or four years.”

She was also feeling unproductive. “I had had three publications as an undergraduate, and here I was as a graduate student: After three years on this project, I didn’t have anything to show for it. And I felt that only I and five other people on the planet cared about what I was working on: how to turn on this one gene in yeast.”

Saey “powered through” her doctorate — “I didn’t want to be getting out of science because it was too hard, or I couldn’t do it, or something” — and then did something completely different.

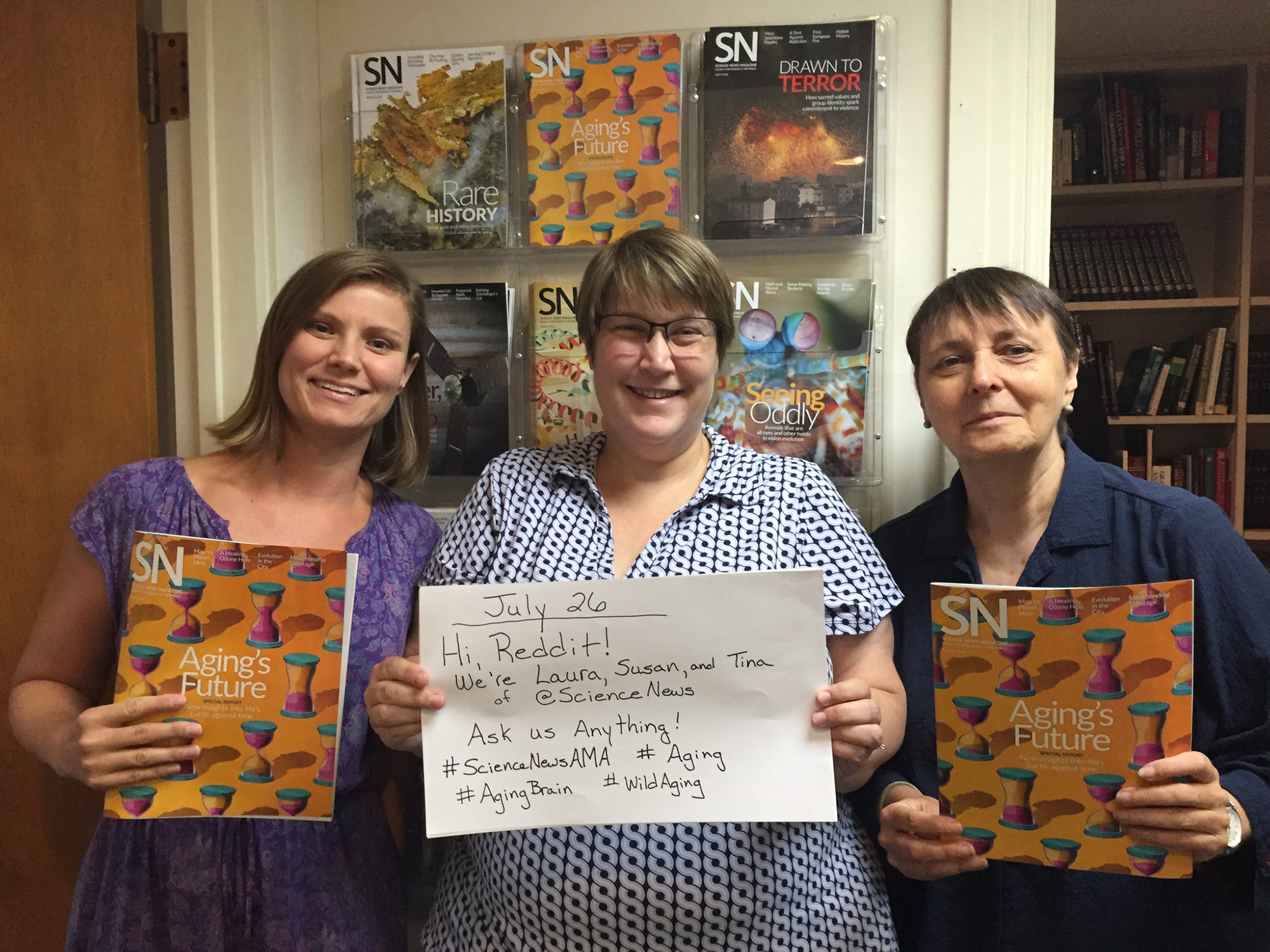

A week after defending her thesis at Washington University in August 1998, she was at Boston University learning to be a journalist. Today, she is the molecular biology writer at Science News, a slim biweekly publication that helps science fans keep up on big developments in science.

Recently, she has written about a sugar found in the air freshener Febreze that cleans cholesterol out of hardened (mouse) arteries; about genetic escape artists who have harmful mutations but no symptoms of the disease the mutations cause; and about evidence that changes in charged atom concentrations, not nerve cell activity, switch the brain from sleep to wake, which may be why people feel so groggy after waking from anesthesia.

Whatever else her job may be, it is not boring.

Does she ever regret her decision to switch careers?

“I remember one time shortly after I started at the Post-Dispatch (her first job as a science writer): I went to a lab to talk to them about their work, and there was a graduate student who was doing a ‘mini-prep.’ I had a moment of panic because I couldn’t remember the exact measurements of the solution that you need to put in the tubes. But then I remembered that I no longer needed to know that.”

So the answer would be a no. This time she has found her niche.

“I will stay at Science News as long as I am able. It’s a place where they really value the science, and I can delve a little deeper, which lets me give people a little better understanding of what the research means,” she says.

“News stories about science aren’t always clear. Having worked at a newspaper, I know that many times that’s because some editor said, ‘Can we take out this science bit.’”

Jumping lanes

Saey didn’t take the most direct route to becoming a science writer, but then almost no one ever does. To be good at science writing, people must have both a strong interest in science and a good ear for language. So it is a profession full of switch hitters and lane jumpers.

Saey had two things going for her in addition to her training as a scientist.

One is that she has always been bookish. “Everyone laughs at me,” she says, “because I always have my Kindle out, and I’m reading while I’m walking down the street.”

She formed this habit early. She grew up in Bladen, Nebraska, a town with a population of fewer than 300 people, set amid the rolling hills of rural Nebraska and surrounded by fields of corn, soybeans and alfalfa. One of her first jobs as a kid was the hard, dirty work of roguing and detasseling corn.

“There were 12 in my graduating class, including the foreign exchange student,” she says.

“In my third- and fourth-grade classroom, there was a corner with a bookshelf and beanbag chair. I’d get done with my assignments, and I’d go get a book and sit in the beanbag chair and read,” she says. “But I’d get in trouble because I wouldn’t hear my teacher calling my reading group or my math group. I’d get in trouble for reading in reading class,” she adds with a laugh.

The second thing she has going for her is a kind of resilience and level-headed pragmatism that comes from living on the High Plains, where help is often not at hand.

In rural Nebraska, agriculture dominates the economy, but Saey’s family wasn’t primarily involved in farming. Instead, her maternal grandfather was a mechanic who subscribed to National Geographic and Popular Mechanics, and her paternal grandfather was a farmer and a truck driver.

Many people in her family drive trucks, one of the few non-farming jobs available in a remote area. Her dad was a truck driver, her mom left a job in a nursing home to get a commercial license, and both her uncle and her youngest brother also drive trucks, as does her husband’s brother.

As a child, Saey would sometimes help her grandfather fix machines, and even today she brings to everything she does the attitude that she should probably try to fix the combine because nobody else is around to do it for her.

This kind of self-reliance came in useful early and often. During her first year in college, she had a work-study job as a dishwasher in a laboratory. “I did wash dishes,” she says, “but my PI also just handed me a bunch of papers and said, ‘Here, write a protocol, and do this project.’”

She explains, “One of his graduate students had discovered a line of tobacco that had ‘cytoplasmic male sterility,’ and he wanted me to isolate and sequence the gene that caused it.” These plants didn’t produce functional pollen, she adds, because of a mutation in their mitochondrial DNA.

Since this was before PCR — the famous polymerase chain reaction that lets scientists amplify tiny amounts of DNA — this meant she had to grow a lot of tobacco to get enough DNA to do the work. (For a musical explanation of PCR, watch The PCR Song.)

And since sequencing was not yet automated, she had to sequence the DNA the hard way, by labeling DNA fragments with radioactive isotopes, letting the fragments race one another through gels and recording their scores by hand.

“I never got it to work,” she says candidly.

But the effort wasn’t wasted. During her junior and senior years, she successfully used these techniques to clone and sequence a bacterial gene that is used to help break down corn to make ethanol.

The same self-reliant attitude characterizes her experiences as a science writer. “At the Post-Dispatch, I had to write about astronomy, physics and geology, as well as biology,” she says. “My PhD work didn’t always prepare me for this.

“For example, I was asked to write about a geology article by a SLU professor that had appeared in Science. I read the abstract, and it said, ‘We report a …,’ and after that I didn’t understand a single word,” she says. “I called the guy up and said, ‘I don’t know anything about geology.’ He said, ‘That’s OK. Come on over and I’ll give you geology 101.’” And he did.

“It turned out that he had discovered the oldest piece of the sea floor ever found on top of a mountain in China. And the age of the rocks allowed him to push the date for plate tectonics back millions of years.” (See P-D article.)

Although she may have felt off-balance, the way she handled this story demonstrated how well prepared she was for a career in science writing. What is important is not knowing everything, but rather knowing what you don’t know and being willing to ask questions until everything makes sense and nothing is dangling loose.

Another story displays fearlessness of a different sort. While she was at Boston University, Saey wrote a radio story on cranberry farming. Her TA for the course, who was also an intern at NPR, played it for the producer there. The producer said, “We need this piece because we have to get Susan Stamberg’s cranberry relish recipe off the air.”

Writing for radio is completely different from writing for print, but with the producer’s help, Saey reworked her script. And on Thanksgiving Day in 1999, her sixth revision bumped Susan Stamberg’s cranberry relish off the air in Boston.

By the time Saey finished her Boston degree, she had impressive credentials: a doctorate in a demanding science discipline; a degree in science journalism; and internships at the Dallas Morning News and Science News.

Even so, she was by no means guaranteed a position. Times were (and continue to be) tough for science reporters. As the Internet “disrupts” print, newspapers and magazines have been steadily losing circulation, and the science writers are often the first to get the pink slip. These days two-thirds of them are freelancers.

But wherever Saey had gone during her extended apprenticeship, she had written good, solid stories that made life easier for the editor. So people remembered her.

Tom Siegfried remembered her.

Siegfried had been her editor when she interned at the Dallas Morning News. Later, after she finished her Boston University degree, Seigfried recommended her to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which was looking for a biotechnology writer. When Seigfried became the editor at Science News, he asked Saey to join him there.

What about that doctorate degree? “I can honestly say that I have never written a story about the topic I studied for a doctorate,” Saey says. “But that doesn’t mean my PhD was wasted. It was good background in what science is and how it works.”

She is too modest, as always. But that, too, is part of being a good science writer. When in doubt, you claim too little rather than too much.

Diana Lutz is the senior news director for science in university public affairs.