I.

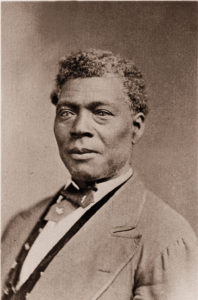

Archer Alexander possessed dangerous knowledge.

Confederate sympathizers aimed to sabotage a bridge over which Union soldiers were soon to pass. The situation was hazardous, especially for Alexander. He was a slave. His owner was among the saboteurs.

So one night in February 1863, Alexander snuck out of his quarters. He conveyed warning.

Disaster was averted. But secessionist suspicion fell quickly on him.

And so Alexander left again, fleeing St. Charles, Missouri, one step ahead of the slave catchers. In downtown St. Louis, a sympathetic butcher directed him to Abigail Adams Eliot. She took Alexander home and introduced him to her husband, William Greenleaf Eliot Jr. — a Unitarian minister, staunch abolitionist and first president of Washington University.

“Dr. Eliot called Archer ‘the most Christian man he ever encountered,’” says Errol Alexander, Archer’s great-great-grandson. “On Sundays they would walk together to church.”

And when the slave catchers finally caught up, “Eliot rescued him.”

II.

The spirit of freedom

Many details of Alexander’s early years have been lost to history. For more than a century, the primary source about his life has been The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, a biography Eliot wrote in 1885.

Eliot reports that Alexander was born into slavery around 1813 on a large Virginia farm owned by a Rev. Delaney. When Delaney died, Alexander was brought to Missouri by the reverend’s son, Thomas Delaney, and later sold to a St. Charles farmer named Hollman.

But Eliot, writing six years after Alexander’s death, relied almost entirely on his own recollections. In The Rattling of the Chains: A True Story of an American Family (2009/2015), Errol Alexander, PhD, presents fresh details and a somewhat different chronology.

According to Errol — who has spent three decades combing historical archives — Archer was born in December 1816, the unacknowledged son of a white family, the Alexanders, who owned his mother. It was the Alexanders who brought him to Missouri in 1829, but in 1837, they sold him to a cousin named Ferrell. He was then sold again to Louis Yosti and finally, in 1844, to Richard Pittman.

In either case, Archer spent most of his adult life in St. Charles working on a farm, where he largely oversaw daily operations. Although unions between those enslaved were not recognized by law, Alexander in mind and spirit married a woman named Louisa, with whom he raised 10 children.

Here, too, Errol adds fresh detail. Drawing on family accounts and slave oral histories, he says that the couple’s youngest child — Alfred, born in 1862 — was likely fathered by Louisa’s owner, a man named James Naylor.

Like Pittman, Naylor was a Confederate sympathizer. Thus, reporting the conspirators — who also had secreted a cache of weapons — was not only a valorous act, it was also retribution for the treatment of Archer’s wife, says Errol.

III.

The capture

For Eliot, Alexander’s arrival at Beaumont Place, as the family home was called, represented a moment of truth. Though he’d long preached against the return of fugitive slaves, Eliot believed in obedience to the law. “What, then, was I to do?”

This:

Within hours, he obtained a 30-day order of protection from Lt. Col. Franklin Dick, the Union provost marshal of St. Louis. The order allowed Alexander to remain in Eliot’s employ until legally claimed.

A few days later, Eliot went to Judge Barton Bates, an acquaintance of Alexander’s master. Eliot explained that he wished to purchase Alexander’s freedom and could pay up to $600. Bates relayed the message, but Eliot received no answer.

Until, that is, one fine spring morning not quite a month later. Leaving for class, Eliot noted a peaceful scene: Alexander working in the yard, Eliot children trailing happily behind, all under the seeming protection of nearby Union barracks. But on the street loitered three rough-looking characters. They gave Eliot pause but seemed to be leaving, and Eliot, with his mind on his lessons, continued to campus.

“They had caught him, sure enough, and had probably got him far beyond my reach already. But, if so, it should not be for want of effort, on my part, to rescue him.”

—William Greenleaf Eliot

That evening, Eliot realized the enormity of his mistake.

The house was in disarray. The children were crying, and the nurse was distracted — only Abigail remained calm in the crisis. The men had been slave catchers, armed with clubs, with knives, with pistols.

They bludgeoned Alexander. They kicked him in the face. They handcuffed him. They hauled him away. The family thought Alexander had been killed before their eyes.

Reading Eliot’s account, one feels his guilt and fury, but also his resolve. “They had caught him, sure enough, and had probably got him far beyond my reach already,” Eliot writes. “But, if so, it should not be for want of effort, on my part, to rescue him.”

IV.

‘Shoot them dead’

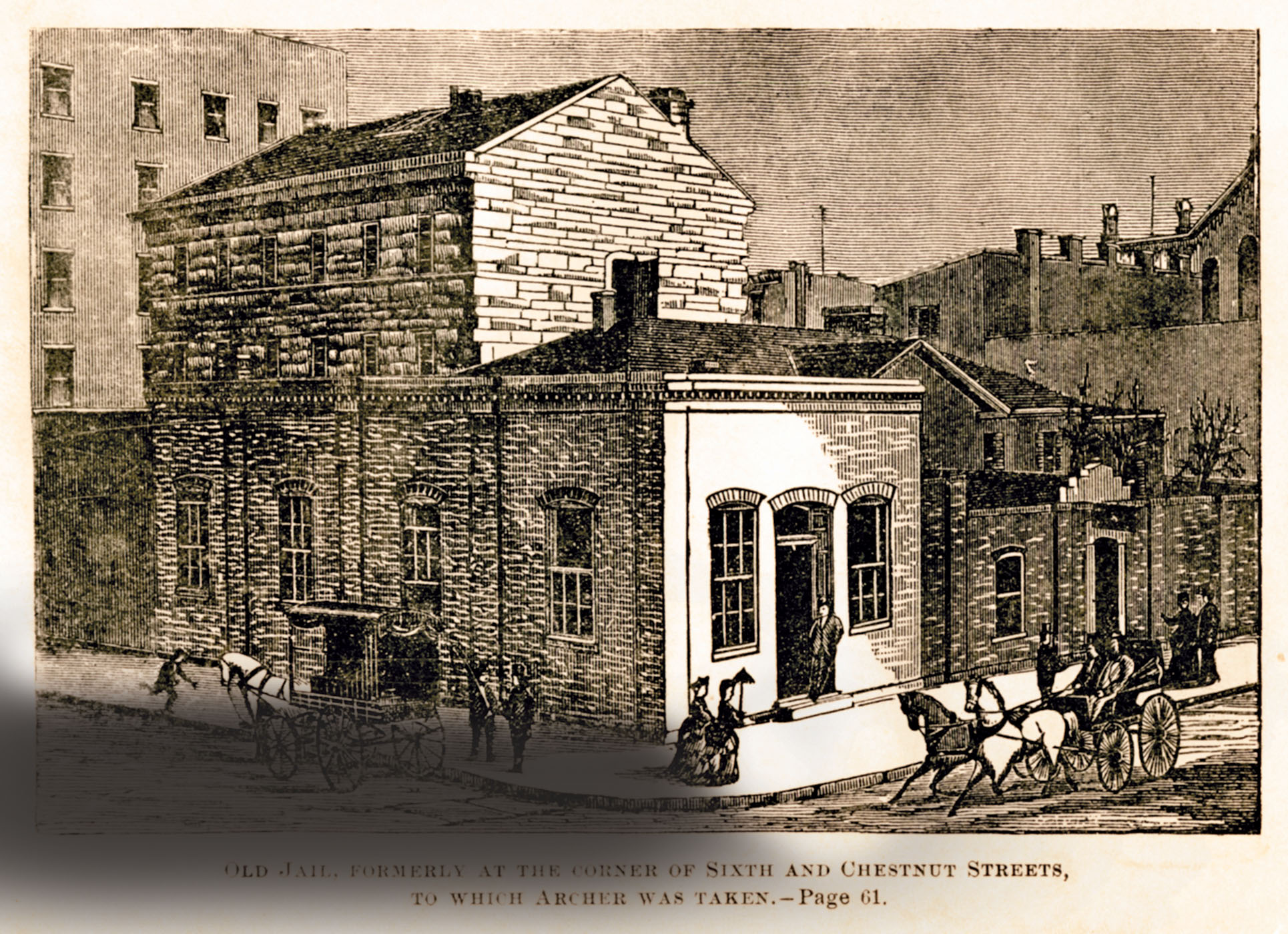

The Old City Jail, located at Sixth and Chestnut, was a strange architectural affair. First-floor gentility — even proportions, a classical cornice — was undone by a ramshackle second, which appeared deposited by tornado.

It was here that Alexander was taken, here where he lay unconscious. But Eliot had one more card to play. Alexander’s 30-day order of protection was 29 days old. Under military law, the fugitive slave had been grabbed too soon.

“Eliot came from New England; his friends were all radical abolitionists,” says Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, PhD, the university’s inaugural Archer Alexander Distinguished Professor in the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. But as a transplant to a more conservative, slave-holding state, “Eliot learned to work the system.”

Eliot took his case to the provost marshal’s office. Capt. James F. Dwight examined the document, interrogated Eliot and summoned local police. Dwight then charged John Egan, who would later become St. Louis’ first detective supervisor, with ensuring Alexander’s return. Eliot reports the exchange between Egan and Dwight:

“What shall we do, captain, if they refuse to give him up?”

“Shoot them on the spot.”

“We are to understand that, Captain Dwight, shoot them on the spot?”

“Yes, shoot them dead if necessary.”

By 10 p.m. the slave catchers were in custody, and Alexander, beaten and bruised, was back at Beaumont Place.

V.

Safety

The next day, Eliot obtained a full order of protection. But the political situation remained volatile. Though President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, it did not apply to slave-holding border states. In Missouri, the “peculiar institution” stood until 1865.

And so, once he’d recuperated sufficiently to travel, Alexander went by steamboat to Alton, Illinois, a free state. There he worked as a farmhand, saved his wages and waited for things to settle down across the Mississippi.

Six months later, when Alexander returned to Eliot’s employ, he deposited $120 in the Provident Savings Bank. It was a good sum: Over the same period, a Union private would have earned $78. He then sent word to Louisa, whose freedom he hoped to purchase.

“My dear husband,” Louisa wrote back.

“I received your letter yesterday, and lost no time in asking Mr. Jim if he would sell me, and what he would take for me. He flew at me, and said I would never get free only at the point of the [bayonet], and there was no use in my ever speaking to him any more about it. I don’t see how I can ever get away except you get soldiers to take me from the house, as he is watching me night and day.”

Eliot read Alexander the letter. But Alexander had a back-up plan: A German farmer who lived nearby had agreed to help Louisa escape. Eliot, sensing slavery’s imminent demise, cautioned that the months of freedom might not be worth the risks of flight.

Alexander disagreed. He worried that Louisa, having sought to leave, might now be endangered. “Her life wasn’t safe if they got mad at her.”

Eliot took the point. The German farmer kept his word. On a moonlit night, Louisa and Nellie, the couple’s young daughter, climbed into an ox-drawn cart and hid beneath the corn shucks.

A horseman soon rode by. He grilled the farmer: “Have you seen Louisa and Nellie?”

“Yes, I saw them at the crossing, as I came along, standing, and looking scared-like, as if they were waiting for somebody,” the farmer coolly replied. “But I have not seen them since.”

As Eliot would later observe, “Literal truth is sometimes the most ingenious falsehood.”

Mother and daughter arrived before dawn. Alexander paid the farmer $20.

VI.

A literate man

Archer and Louisa were soon reunited with two more daughters. They learned that a son, Tom, had been killed in action while serving in the Union army. Archer was grieved but proud. “I couldn’t do it myself,” he told Eliot, “but I thank the Lord my boy did it.”

Louisa died shortly after the war ended, under suspicious circumstances. Returning to “Mr. Jim’s” house, to collect her few belongings, Louisa reportedly took ill and died two days later. Alexander mourned a year, then remarried.

Alexander stayed at Beaumont Place for a time, then took rooms of his own. Still he and Eliot remained close. According to Errol Alexander, on Sunday mornings, the pair would walk together to Eliot’s First Unitarian Church. Alexander worked the organ bellows while Eliot addressed the congregation. When Eliot’s mother died in 1875, “Archer was the only person he’d talk to.”

Alexander acquired a pocket-watch, which he saw as a symbol of freedom. “Slaves did not need watches,” Errol explains.

Alexander also learned to read.

“It was an educated household,” Errol says. “They had weekly recitations from Dickens and Shakespeare. Julia [Alexander’s second wife] could speak German. You could not be in that household and not learn how to read.”

Errol credits Eliot’s son, Christopher, with tutoring his great-great-grandfather. The accomplishment is even more impressive given that, prior to the war, many slave states had passed anti-literacy laws.

“Reading was a political act,” says Maffly-Kipp, an authority on slave narratives and author, most recently, of Setting Down the Sacred Past: African-American Race Histories (Harvard University Press, 2010). She points out that in 1847, when Missouri legislators banned education for blacks, the Rev. John Berry Meachum, himself a former slave, opened his Floating Freedom School in a steamboat on the Mississippi River.

“Once you develop skills of literacy, you’re able to tell your own history,” Maffly-Kipp explains. “It’s a way of organizing community and establishing political legitimacy.”

For the Alexander family, Archer’s values still echo today. “My grandfather used to quote Shakespeare,” says Errol, who taught business and psychology at the University of Stirling, Scotland, before retiring in 1996. “He didn’t go to college. Where did he get that?

“The fact that Archer could learn to read, as a man in his 50s … he symbolized what is best about education,” Errol adds. “He died a literate man.”

Archer Alexander passed away in 1879. The funeral was held downtown, at the African Methodist Church on Lucas Avenue. Eliot officiated.

Alexander left his watch to Christopher.

Liam Otten is senior news director of the arts and humanities in Public Affairs.