C. Prakash Gyawali grew up on the other side of the world, in Kathmandu, Nepal, about 100 miles from Mount Everest. Although the city sits in a valley, it is about 4,600 feet above sea level, or about 4,000 feet higher than St. Louis.

“If you want to know whether I miss mountains, the answer is yes. I do,” he said. “I have walked around and climbed every little hill in Missouri for many years.”

Gyawali went to high school in India, completed his pre-medical training in physics, chemistry and biology there and then earned a medical degree from the University of Calicut in South India.

But a fortunate meeting with a Washington University chief resident in 1993 led him several thousand miles away to the School of Medicine. And he’s been here ever since.

Gyawali came to St. Louis hoping to become a gastroenterologist.

“At the time, I didn’t know what I would specialize in,” he said. “I only knew I wanted to be a gastroenterologist, and I wanted to work in an academic center.”

He wanted to interact with patients, and he was interested in “new gadgetry,” so his eventual career choice — involving the used of rather complicated gadgets and algorithms to try to understand how muscle contractions in the esophagus move food to the stomach — made sense.

At the time he arrived in St. Louis, most patients with problems linked to the esophagus received unrefined, conventional testing, providing only limited information about heartburn related to reflux or the rare disorder known as achalasia.

In the early 1990s, most of the focus was on symptoms. Patients with achalasia regurgitate their food and experience swallowing difficulty, chest pain and unintended weight loss. But other disorders such as reflux disease, other types of esophageal inflammation and even esophageal cancer have similar symptoms. So it’s important for doctors to determine what’s causing the problem before they try to treat it.

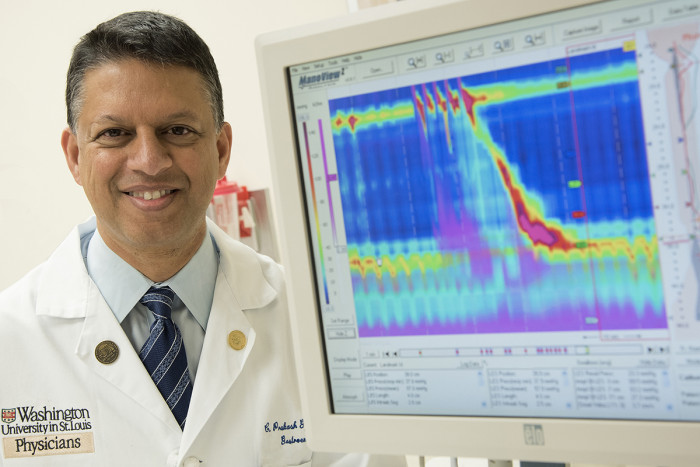

When Gyawali began his residency, his eventual mentor, Ray Clouse, MD, then a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology, introduced him to a brand-new way to do that, a technique called high-resolution esophageal manometry. It allows doctors to precisely evaluate motor function in the esophagus and in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract better than the older conventional systems.

Because patterns of esophageal muscle contraction tend to be different in different patients, learning about those patterns can help explain why individuals develop particular problems, from reflux to achalasia.

“I began collaborating with Ray through my residency and fellowship, and that’s when I began to develop a deep interest in the field,” Gyawali said. “In the years since, it’s become the primary focus of my career.”

Moving from symptoms to causes

Gyawali uses manometry and reflux monitoring to learn what’s behind a patient’s symptoms so that those problems can be addressed.

“The most common condition affecting the esophagus is reflux disease,” he said. “If patients have acids coming up from the stomach into the esophagus, they often get severe heartburn, so if they come see us and have those symptoms, we begin by managing them as if they have reflux. But if they don’t get better, we start looking for alternate mechanisms that could be causing the problem.”

As part of that search, Gyawali sometimes will run a catheter to a patient’s stomach and then give that person sips of water to drink. As the water travels from the mouth to the stomach, he measures how muscles in the esophagus transport the liquid.

Or he may place a wireless transmitter into a patient’s esophagus and send that person home for 48-86 hours. Meanwhile, the device keeps track of acid levels in the esophagus. If they’re high, it could indicate the need for aggressive treatment of reflux disease.

“With these and other tests, we keep refining the classifications of disease every few years so that we can better report what we’re finding in these precise tests of muscle movement in the esophagus and elsewhere in the GI tract,” he said.

Another goal is to tailor treatments to individual patients. Little by little, Gyawali explained, the field is learning about the underlying causes of patients’ symptoms.

On the road

Part of refining those classifications involves occasional travel to far-away scientific meetings. Sometimes they’re far enough away that he can get together with members of his family, some of whom still live in Nepal.

His mother and a brother are in Kathmandu. The two survived last spring’s earthquake but had to find a new place to live. Their landlord asked them to move so he could live in the home because his own residence was damaged in the earthquake.

Gyawali has two younger brothers. One works for the Atlanta-based humanitarian organization CARE, and lives with his family in Bangkok. Back in Kathmandu, the other owns an Internet travel company.

Gyawali and his wife, Laura, have three young children.

The family’s television is frequently tuned to Cardinals baseball games from April through October, often playing in the background when Gyawali takes work home.

“I consider myself really blessed that I came to St. Louis when this field I eventually adopted had openings for someone like me,” he said. “It’s a rather narrow field, and for a long time, it was considered to be a very mysterious aspect of gastroenterology. But I really enjoy working with patients and using these complicated gadgets to occasionally solve some mysteries.”

Originally published by the School of Medicine