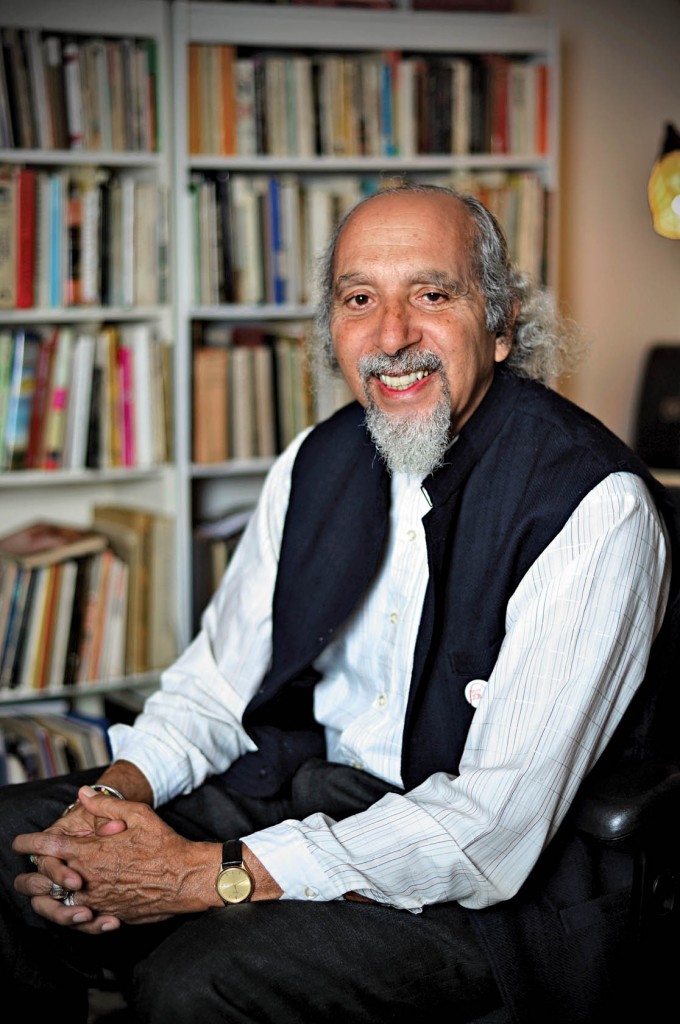

(Photo: James Byard)

In 2006, poet Rodney Jones wrote, “a poet is as anachronistic as a blacksmith.” Although poet might suggest to some an old way of doing things, Michael Castro, MA ’71, PhD ’81, knows that the job of the poet is to tell the truth, to bear witness and to have the courage to say and write what he feels and sees now. Named poet laureate of St. Louis on Jan. 1, 2015, Castro’s truthful and compassionate voice might be the timely and necessary balm the city needs to heal from the turbulence in Ferguson. There is nothing outdated about this need — and nothing anachronistic in wanting a poet to summon his powers and words to help make sense of things. Castro has stepped in just in time.

Before his nomination, Castro may have been best known in St. Louis as the founding editor of River Styx, a magazine and reading venue for poets and musicians begun in 1975. The magazine has won many prestigious awards, and it has received grants and support from the National Endowment for the Arts. The list of poets published over the years in River Styx is staggering. The magazine has featured works by Charles Simic, Czeslaw Milosz, Mona Van Duyn, Robert Hass and Derek Walcott, to name just a few.

Growing up in New York City, Castro was always interested in language and poetry. The poets who first grabbed his attention were diverse. It was his mother’s copy of Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet that quickly caught Castro’s ear, then later, Frederico Garcia Lorca’s Poet in New York.

“Lorca’s poetry was like music, and it made me want to write,” Castro says. In New York, Castro listened to jazz at nightclubs and read voraciously. It wasn’t just Lorca who drew him to poetry. Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg inspired him as well, with their wild sentences and disdain of traditional verse.

Castro began developing his own style when he moved to St. Louis in 1967. “I started writing poems in the form of songs,” Castro recalls. “I met some St. Louis poets, and we used to meet several times a week at Dan Spell’s apartment. And we would read what we were writing and poets who turned us on. It was a shaping period.”

Four members of the group published Ripple, a book of poems printed on rice paper. “When the book was published, we distributed it in St. Louis and sent several copies to Gary Snyder, an influential Beat poet. One reached Allen Ginsberg,” Castro says. “Over the next few years, I ran into people who had seen my poem ‘Brown Rice’ on Ginsberg’s wall. The news that Ginsberg had put the poem up was affirmation. I admired him, and he had truly published my poem.”

Ever multicultural, Castro wanted to read more than the usual poets and writers. Native American literature also called him to listen and to give attention, and he attended Washington University to study American culture and Native American mythology.

“As a wannabe American poet with an urban background, I was interested in Native American lit in order to cultivate a relationship with the natural world.”

Michael Castro

“Actually, I was interested in Native American literature as a poet more than as a scholar,” Castro says. “As a wannabe American poet with an urban background, I was interested in Native American lit in order to cultivate a relationship with the natural world. I felt I was closer to the roots of the continent on which I actually lived when studying Native American mythology.”

Over his career, Castro has published 10 collections of poetry and has had poems appear in more than 100 magazines. His poems exhibit a keen ear and a fearless eye, which may be why he was selected from a pool of 64 candidates to be St. Louis’ first poet laureate. Castro came ready with a rich background in literature, the word and justice.

As Castro said during his inauguration on Jan. 31, 2015, “Time for St. Lou Is, truly, to become / St. Lou Us. All of us — one polity — / with mutual R-E-S-P-E-C-T, / a unity community, / less of me & more of we.”