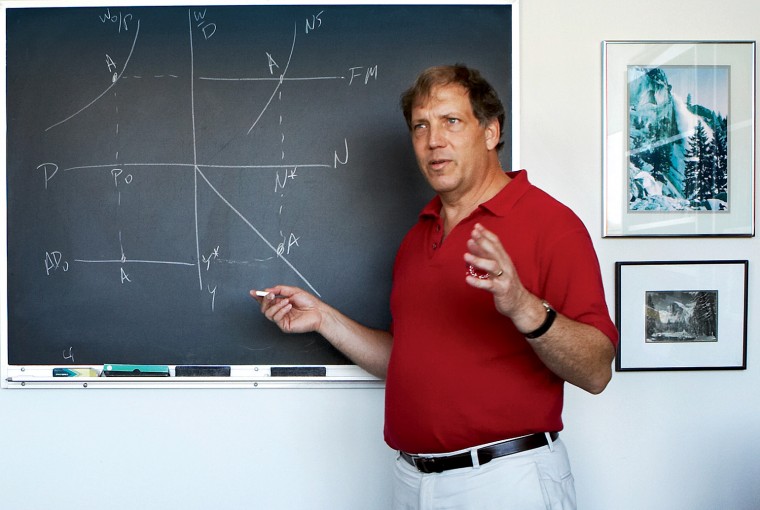

“Economic Realities of the American Dream,” a course that Mark Rank teaches with Steven Fazzari, PhD, the Bert A. and Jeanette L. Lynch Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences, takes an interdisciplinary look at the issues raised in Chasing the American Dream. The course examines the American Dream’s historical meaning, the traditional pathways to reach it, the current obstacles to achieving it and its viability in the future.

“The American Dream is a nuanced concept,” Fazzari says. “Mark gets credit for how we define it, but the phrase ‘economic realities’ in the course title comes from my discipline. From an economic point of view, a central part of the American Dream is that the next generation is supposed to do better than its predecessor. That requires economic growth, which leads to a discussion of where economic growth comes from. The question I pose is the extent to which the U.S. economy has supported the American Dream historically, and will support it going forward.”

Fazzari’s scholarly approach is informed by his own Midwestern middle-class upbringing in Racine, Wis. His father was employed at an iron foundry, and Fazzari got hired on as summer help. He worked alongside men whose union wages gave their family consumer spending power on a single income.

“The U.S. was the dominant political and economic power in the world in those days,” he says, “and that was considered the way it should be. If you were diligent, worked hard and played by the rules, things would work out for you.”

The Great Recession, Fazzari says, turned a lot of the conventional wisdom about the American Dream upside down. “Our growth in the decades prior to the Great Recession required a household spending boom that was unsustainable,” he says. “The only way middle-class households as a group could maintain a spending level that produced full employment was by taking on increasing amounts of debt. When the real estate bubble burst, the debt-financed spending stopped, and the economy crashed.” His estimates show that these problems were concentrated in the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution. Debt among the top 5 percent of income earners was relatively stable compared to their fast-growing income.

Any discussion of how to help American families have a secure economic life, Fazzari says, requires that you first recognize that the definition of a secure economic life changes.

“Twenty years ago, it didn’t include having a cell phone, but you have to have one today. When talking about rising economic inequality, however, some of the pundits say, ‘They have all this stuff — what’s the problem?’ That’s misleading. Just saying that you’re not starving and have a few luxuries by historical standards doesn’t mean that you’re doing well by today’s standards,” Fazzari says. “Today, the median income in the U.S. is about $50,000 a year. Depending on where you live, you and your family may not be able to live the American Dream, as depicted in the media, on that amount.”

Fazzari says he has no magic bullet, but he does offer a target: shared prosperity.

“If you look at the post–World War II decades, you see rising per-capita income, spread broadly,” he says. “There hasn’t been much shared prosperity since 1980. That’s because the rewards from economic growth shifted from all stakeholders, including workers, to rewarding mostly top management, financial institutions and investors. In the course, we discuss the redistribution of wealth — tax the rich, give to the poor — but that isn’t fully consistent with the principles of the American Dream that says people earn their ticket to the middle class. Policy changes are going to be necessary, and shared prosperity is a great organizing principle.”