“The American Dream is that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”

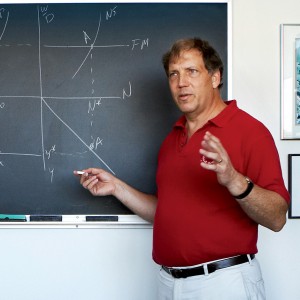

With those words, writer and historian James Truslow Adams coined the phrase “American Dream” in his 1931 book The Epic of America. If that date seems surprisingly recent, it’s because the idea of the American Dream — boundless opportunity for those willing to pull up their socks and go for it — has been part of our cultural fabric since the Founding Fathers, says Mark R. Rank, the Herbert S. Hadley Professor of Social Welfare at Washington University’s Brown School. Moreover, what most of us think the American Dream means in abstract is fundamentally different from what most American dreamers personally hope to gain.

“People think the American Dream — the concept — is about having riches beyond imagination,” Rank says, “but if you ask them what it really means to them as individuals, that goal is near the bottom of the list. For the average person, the American Dream boils down to three things: being able to do with your life what you want to do, economic security, and hope and optimism.”

Rank, a leading national expert on poverty, has spent his career looking at those for whom the American Dream hasn’t come true. In his latest book — Chasing the American Dream: Understanding What Shapes Our Fortunes (Oxford University Press, 2014), written with co-author Thomas A. Hirschl, professor of development sociology at Cornell University, and former student Kirk A. Foster, MSW ’02, PhD ’11, now assistant professor of social work at the University of South Carolina — Rank explores why a goal that is a possibility, or even a probability, for some is an illusion for so many others.

For those familiar with Rank’s previous two books — Living on the Edge: The Realities of Welfare in America (Columbia University Press, 1995) and One Nation, Underprivileged: Why American Poverty Affects Us All (Oxford University Press, 2005) — this latest work continues that conversation.

Chasing the American Dream overlays a detailed analysis of longitudinal information collected in the University of Michigan’s Panel Study of Income Dynamics (income data from 5,000 American households followed since 1968) with in-depth stories of 75 average Americans interviewed by Rank and Foster, and other material gleaned from focus groups.

“I have always cared about social justice and social injustice,” Rank says, “and I’m interested in the economic issues surrounding poverty. That poverty exists in a society where we have so much is a real paradox.”

One alarming finding in Rank’s latest research is that poverty is just around the corner for more of us than we think. In fact, he says, it is the new norm.

“Many American families are one paycheck away from poverty. Studying people aged 25 to 60, we found that 54 percent will spend at least one year near or below the poverty line during their lives,” Rank says. The number of people who will experience economic insecurity, he adds, soars to 80 percent if you factor in related events such as unemployment or welfare utilization.

A year, of course, is not a lifetime, but the statistics for those who are more permanently situated at the top or the bottom speak volumes about the supposedly level playing field offered by the American Dream. “It’s called cumulative inequality,” Rank says, “and it says that where you start in life leads to further advantage or disadvantage.”

Rank’s research shows that the sons born into almost every income level will likely earn more than their fathers. Despite that, the bottom-to-top, rags-to-riches litany of the American Dream actually occurs less than 8 percent of the time. “For every one of them, there are 10 others who work just as hard and don’t achieve that economic level,” he says. “We tend to say that anyone can do it, but that’s not true. There just aren’t enough slots open for everyone to rise to the top.” Forty-two percent born into the bottom quintile remain there, he says, as do 36 percent who are born at the top quintile.

“Our poverty level is twice that of Europe, and one of the basic reasons is that we do so little to prevent people from falling into poverty, and then so little when they do.”

Mark Rank

“Our poverty level is twice that of Europe, and one of the basic reasons is that we do so little to prevent people from falling into poverty, and then so little when they do,” Rank says. “Europeans have a much stronger social safety net, which includes universal health care and low-cost housing and child care for low-income families. We fear a ‘culture of dependency,’ so we do nothing, often at greater long-term cost.”

People even explain away their own troubles differently from those of others, Rank says. “Asked about themselves and why they needed assistance, they say, ‘I lost my job, my family split up, I got sick,’ or give some other reason that was out of their control,” he says. “When asked about others, however, they say it is ‘because they’re lazy, drinking, using drugs,’ or another basic character flaw.”

Surprisingly, perhaps, Americans have almost an equal chance — 77 percent — of being comparatively wealthy, or living in a household with an income of more than $100,000. Again, though, that’s the statistic for just one year. Given the size of both percentages, that means most of us will experience both the high and the low. The instability demonstrated by this yo-yo effect is what the average person feels, and what concerns Rank most.

“The three decades following World War II saw the rise of the American middle class and an enormous consumer economy,” he says. “In the three decades following the election of President Reagan in 1980, we saw the country become increasingly conservative as well as real pressure on wages and benefits caused by globalization. This combination started a real economic retrenchment, in which only the top end made gains.”

The way schools are set up, however, some kids are getting a good education and some are not. “That’s fundamentally wrong.”

Mark Rank

Consider the education of children, Rank says. It is in the best interest of the entire country to have a well-educated workforce. The way schools are set up, however, some kids are getting a good education and some are not. “That’s fundamentally wrong,” Rank says. “The Pledge of Allegiance states ‘liberty and justice for all,’ but it’s not for all. We continue to attempt to privatize sectors that have traditionally been in the public domain. The idea is to let the market work. That’s fine, but if you just let it operate on its own, you’re going to wind up with extreme inequality. The haves will get more, and the have-nots will get less, and you end up with a vacuum in the middle.”

If the American Dream, however defined, has become a broken dream for so many, can it be restored? Rank talks about how the pathway to the American Dream has been narrowed. What is essential, he says, is to find ways to widen that path to accommodate more people. Otherwise, the top will continue to prosper, the bottom will continue to suffer, and the middle — which should be our greatest strength — will continue to struggle. The end result, he adds, will resemble a Third World country.

“It’s an uphill battle,” Rank says. “What we need are good public schools and jobs that provide a decent wage and health insurance and that can support a family. The easy answer, in conversation, is to have an economy with jobs for all who need them. In truth, it’s hard work.”

Rank proposes that we pursue a “virtuous cycle” — strengthen our human capital and skills broadly to reap the benefits of a more innovative, productive society. Such an investment in our fellow citizens does not create a culture of dependency, he says. Instead, it creates the best-possible win-win scenario, because, in truth, we will be investing in ourselves.

Robert S. Benchley is a freelance writer based in Miami.