Writers are often told to “write what you know.” If that be true, alumni authors of recently published books possess remarkably varied knowledge.

Their nonfiction works deal with a crucial but little-known World War II secret operation, improving doctor-patient communication, a basketball coach who helped change an inner-city neighborhood, making your workplace more creative, aging with style and humor, the eccentric genius of George E. Ohr and the lives of two Nobel Prize winners who collaborated in the French Resistance.

Similarly, alumni fictional works run the topical gamut: the impact of GIs on a Massachusetts community during World War II, the struggles of a Southern debutante at an equestrienne boarding school during the Depression, the life and commercialization of an 11-year-old pop-music megastar and political intrigue among dragons and humans in the mythical kingdom of Goredd.

Meet the authors below and learn more about their books.

A. E. Hotchner, AB ’40, JD ’40

Living the writing life

Best known for best-sellers Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir and King of the Hill, his St. Louis childhood memoir, A. E. Hotchner, AB ’40, JD ’40, Honorary Doctorate ’92, continues to live the writing life at age 93. His new book, O.J. in the Morning, G&T at Night: Spirited Dispatches on Aging with Joie de Vivre (St. Martin’s Press, 2013), works as both a guidebook and a travel warning to those venturing forth chronologically.

“Everybody looks at the numbers more than themselves,” Hotchner says. “Because they’re 65, they cut back — but maybe you’re really 50. You’re going to age, but you should do it with a good sense of living and have a good time about it.”

Which Hotchner seems to do. At his 50-year Washington University class reunion, when passed a hand mic to give his name and a thumbnail summary of his life, he identified himself as Eugene O’Neill, he recounts in his new book, “and said that since graduation it had been a long day’s journey into night.”

Hotchner continues to play golf and tennis, to travel on safaris and to write, always in longhand on a yellow pad, he says, never with a computer or typewriter, to get closer to the page. “When your fingers actually write it, it’s more personal.”

His friend Ernest Hemingway also wrote in longhand, Hotchner says, except for dialogue, when he turned to the typewriter “for faster rhythms, the way people talked.”

Hotchner, who also works as a novelist and playwright, has benefited from close acquaintanceship with other noted writers as well. “The ones I got to know best were Edna Ferber and Dorothy Parker. One thing I understood from them is to write from what you know and what you feel, from your true emotions, not invention,” he says.

Hotchner is now at work writing a musical play based on his 1975 biography of actress and singer Doris Day, a close friend.

“Too much to do,” Hotchner says, “too little time to do it.”

Jan Greenberg, AB ’64

Collaboration key to success

Unlike some writers who consider the editing process an intrusion, Jan Greenberg, AB ’64 (English), sees it as vitally important.

“It’s wonderful and instructive to get feedback,” Greenberg says. “But you have to be with an editor who believes in your work.”

Greenberg, from the start of her writing career, found such a person. In 1978, Sandra Jordan, an editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, discovered Greenberg’s first book in a pile of unsolicited manuscripts. “A little encouragement went a long way,” she says.

Throughout seven novels, Greenberg turned family fodder — the trials and tribulations of her three then-teenage daughters — into page-turners for young readers.

Once her daughters grew up and moved out of the house, however, Greenberg said childhood stories were no longer giving her pause. That’s when she found inspiration through another family member.

“Sandra and I decided at the beginning that we would concentrate on post World War II artists. Since a lot of the artists were not household names, we had to bring the reader in through story.”

Jan Greenberg

“My husband, Ronnie, is an art dealer in St. Louis, so our house was often filled with artists and art talk,” she says. “I did research, this was in the early ’90s, and discovered there were no books about contemporary artists for young people.”

While teaching aesthetic education at Webster University, Greenberg developed a system for looking at art. “Revising it for children, I thought, could fill a gap in the bookshelf.” She reconnected with Jordan, and the two teamed up this time as writing partners.

Their collaboration has produced 12 beautifully designed titles, including the most recent, The Mad Potter: George E. Ohr, Eccentric Genius. Their Ballet for Martha: Making Appalachian Spring was an Orbis Pictus Award winner, and for their body of work, the two were recognized with the 2013 Award for Nonfiction by the Children’s Literary Guild of Washington, D.C.

Leana Wen, MD ’07

Bridging the patient-doctor divide

When Leana Wen, MD ’07, was in her second year of medical school at Washington University, her mother was diagnosed with cancer. For seven years, until her mother’s death, Wen helped her navigate the medical system. “In the process, I saw how disconnected doctors and patients have become, how out of control patients can feel,” she says, “and how disempowering our health system is.”

Ever since, Wen has dedicated herself to bringing doctors and patients closer together. Her book When Doctors Don’t Listen: How to Avoid Misdiagnoses and Unnecessary Tests (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2012), co-authored with Harvard emergency physician Joshua Kosowsky, MD, gives patients — and doctors — ways to avoid “cookbook” medicine that can lead to misdiagnoses.

“The book as conceived was originally intended for doctors,” Wen says. “But I realized that doctors are not effective without good patient input, and both needed to be involved.”

Using case histories where patient-doctor miscommunication resulted in misdiagnoses, the book exposes how training physicians to zero in on the “chief complaint” triggers rigid diagnostic pathways that often miss the mark. To remedy this, Wen and Kosowsky prescribe “8 Pillars to Better Diagnosis” for patients and physicians.

Researching and writing the book changed the way she views and practices medicine, says Wen, who is now director of patient-centered- care research in George Washington University’s Department of Emergency Medicine.

“I loved conducting the interviews. I was able to talk to people — not patients, but people — about their health-care experiences. I sought different information than I would have as their doctor and learned more.”

Squeezing in time while working odd ER hours to write the book was “cathartic,” Wen says. “The process changed how I view medicine and how I provide medical care.”

Robert Switky, AB ’04

Exposing a WWII secret operation

In a tale of daring and secrecy that will surprise historians and the average World War II buff, Robert Switky, AB ’84 (French and international development), explores a little-known operation that may have changed the course of the war.

In Wealth of an Empire: The Treasure Shipments That Saved Britain and the World (Potomac Books, 2013), Switky researched national archives, museums and libraries on both sides of the Atlantic to document how the British secretly transferred virtually all its gold and dollar-based financial securities to the United States and Canada across the perilous waters of the North Atlantic.

“The operation was so secret that most of the principal decision-makers — including the prolific Winston Churchill — wrote very little about it either in their memoirs or in their official capacities,” Switky says. “To this day, most World War II history books say nothing at all about the treasure shipments.”

Switky, PhD, who teaches political science at Sonoma State University in California, has previously written articles and co-authored books aimed at academic audiences. But with Wealth of an Empire, he needed to adjust his approach to writing. “Academic publications usually receive praise only for their research findings and their intellectual impact, not their prose,” Switky says. “I realized that I had to retool my writing style for a book designed for the general public.”

Switky hopes his book will hold wide appeal, as it tells many stories in one. “The pivotal events take place on the high seas and in the boardrooms of central banks,” he says. “It’s a political story about American isolationists and British appeasers. And, it’s a diplomatic story of a fragile but defiant Britain, its valuable Canadian military and political supporters, and its reluctant American ally.”

For additional information, visit the website https://www.sonoma.edu/users/s/switky/.

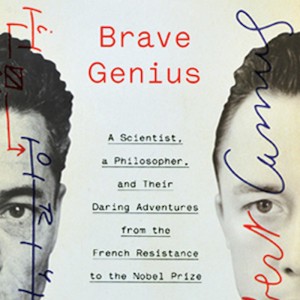

Sean B. Carroll, PhD, AB ’79

Reaching beyond disciplinary boundaries

Sean B. Carroll, PhD, AB ’79 (biology), was an award-winning, internationally recognized biologist and author of five books on genetics and evolution. Yet, he decided to spend two-and-a-half years writing a book centered on World War II history, the French Resistance, and the friendship between two Nobel Prize winners, writer-philosopher Albert Camus and biologist Jacques Monod. This was a seemingly risky stretch for a scientist — which now looks like a smart career move.

Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize (Crown Publishers, 2013) has not only garnered widespread critical acclaim, it has changed the man who wrote it.

“There were two great rewards in writing the book,” says Carroll, who leads the Department of Science Education at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and is the Allan Wilson Professor of Molecular Biology and Genetics at the University of Wisconsin. “The foremost being the internal reward of the creative challenge, wrestling with my own thoughts and trying to tell a good story.”

He seems to have succeeded. Brave Genius has been described as “gripping,” “suspenseful” and “masterful” by, respectively, the Washington Post, New York Times and Nature.

His second reward came via his research, traveling not only to France but also back in time.

“I was astounded that I got the opportunity to meet family members, some of the characters connected to the story, people who are still living, such as Monod’s assistant in the Resistance, Geneviève Noufflard, who is 93, and Agnès Ullman, who was my connection to many people around Paris.

“To meet these people,” Carroll says, “to be welcomed into their homes, to be trusted with their stories — which may have still been difficult for them to tell, stressful even after so many years, and being told for the first time…”

For once, words fail him.

Scott Witthoft, BSCE ’99

Making space work creatively

Getting more sleep, says Scott Witthoft, BSCE ’99, was a prime motivator in his writing Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration (Wiley, 2012) with co-author Scott Doorley.

“Make Space is an effort to extend our reach in designing collaborative spaces at the Stanford d.school” — the university’s Institute of Design, where Witthoft is co-director of the Environments Collaborative. “The book has been one way to increase the supply of help based on burgeoning demand.”

Witthoft says the book can help classroom teachers, office managers, baristas and others take control of their workspaces to affect behaviors. “We’ve designed an experience to help people change the way their cultures work, share, learn and teach. Anyone who has any interest at all in designing better ways to work and create with people, might find something interesting or challenging within Make Space.”

Employing ample illustrations and a modular structure, the book is a compendium of tools, situations, space studies and insights designed to spark creativity and collaboration.

“An architect or a facilities crew may be likely governors of space,” Witthoft says, “but our observations suggest that really cool opportunities are percolating where people at all levels of work are taking control of space as a tool for change.”

Likewise, in writing the book, Witthoft worked to create a practical, user-friendly tool that actually got used. “Many people sit down and read Make Space front to back. Most don’t,” he says. “The goal of keeping the book off the shelf required personal engagement and interaction totally outside the page. We get stories all the time from people who have flipped open the book, read something, and then applied that in a totally different context. Brilliant!”

Wayne Drash, AB ’94

Chronicling a miracle season

In On These Courts: A Miracle Season That Changed a City, a Once-Future Star, and a Team Forever (Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 2013), Wayne Drash tells how a wealthy former NBA star, Penny Hardaway, returned to his poverty-stricken Memphis neighborhood to coach middle school basketball — and change lives.

“On These Courts demonstrates the power of social change and that good can be done when a leader steps up, takes a stand in a gang-ridden community, and shows at-risk youth a different path,” says Drash, AB ’94 (English and American literature), a CNN.com senior producer.

Once the face of Nike, Hardaway, who had his career shortened by injuries, continued to support programs in his old neighborhood. However, he saw that people there needed his time more than his money.

“With Penny’s leadership, the kids’ grades went up, neighborhood gangs struck a truce, and his team ultimately won the state championship in dramatic fashion — Penny’s first-ever championship,” Drash says.

“On These Courts is really about the importance of being a positive role model. No matter what our career may be, there is always the ‘after-career,’ where you can use what you know and what you love and start to give back,” he continues.

For Drash, whose online writing is read daily by millions, writing and publishing On These Courts, his first book, has been an emotional roller coaster. “I go from those astronomical numbers to selling a few thousand copies of my book. That resulted in extreme highs and lows of being an author,” he says. “But I wouldn’t trade it for anything. I accomplished a goal that I made as a freshman at Washington University — that I would write a book one day.”

Elizabeth Graver, MFA ’90

Grappling with social change

As a child, Elizabeth Graver invented an imaginary world. She and her best friend created a (high-drama) farm family with an entire cast of characters, including two doll daughters.

“Then, I turned thirteen, and playing with dolls became something to hide. I felt a real loss at that stage,” says Graver, MFA ’90. “At first, writing was a sort of replacement, a way to enter a dream world where anything could happen. Then I started to write more regularly, to need to do it for my happiness and sanity. As an adult, I marvel that my work still contains so much play.”

Graver’s critically acclaimed work includes four novels, with the latest, The End of the Point (HarperCollins, 2013), long-listed for the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction.

The book’s setting is Ashaunt Point, a sliver of land jutting into Buzzards Bay, Mass., and summer home to generations of the Porter family. Beginning with the upheaval brought by the U.S. Army’s arrival to the Point in 1942 and continuing through the Vietnam War and beyond, Graver’s protagonists discover that even Ashaunt, a place out of time, cannot escape the seismic cultural changes of the 20th century.

“Most of the time I work in the cracks between other things. I have no special candles or token objects, no special chair. A pen and scrap paper in my car. A pen and scrap paper by my bed. A laptop that I love more than anyone should love a machine.”

Elizabeth Graver

The significance of place is not lost on Graver as it relates to her own life. She says Washington U., where she had “the amazing good fortune” to study with such professors as Stanley Elkin, Deborah Eisenberg, Angela Carter and Alain Robbe-Grillet, was pivotal to the early days of her career.

“I’ve been very lucky,” she says. She found her literary agent after publishing her very first story. She has worked with the same editor for all four of her novels. And since 1993, she has taught literature and creative writing at Boston College.

“I write literary fiction. I want to make art, rather than produce for the marketplace,” Graver says. “The continuity I’ve had with my agent, my editor and my job allows me (perhaps paradoxically) to take greater risks with my books.”

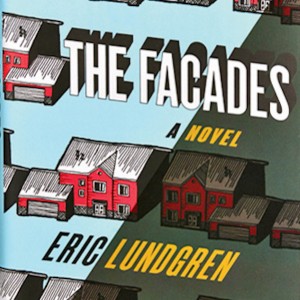

Anton DiSclafani, MFA ’06

Coming of age in a boarding school

For Anton DiSclafani, MFA ’06, two of her favorite hobbies — ones that help her recharge her writing — are riding horses and reading.

It’s no accident, then, that in DiSclafani’s first novel, The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls (Riverhead Books/Penguin Group, 2013), horseback riding features prominently in the story’s narrative. For the story’s young heroine, riding horses provides her with a sense of well-being and of belonging, and provides her a lifeline as she leaves an idyllic world where she’s an isolated insider for another where’s she’s a total stranger to the place’s customs and its people.

Set in the 1930s, in the midst of the Great Depression, DiSclafani’s novel tells the story of a strong-willed 15-year-old, Thea Atwell. Thea has been cast away from her Florida home on a citrus farm, where she and her twin brother roamed freely, to an equestrienne boarding school in the Blue Ridge Mountains. According to the publisher, “As Thea grapples with her responsibility for the events of the past year … she must navigate the politics and competition of friendship as well as her own sexual awakening … her experience will change her sense of what is possible for herself, her family, and her country.”

For DiSclafani herself, a writer-in-residence at Washington University, her world and the sense of what’s possible has definitely changed over the past year. Her first novel was published after a reported seven-figure publisher bidding war, which included foreign rights in 12 countries. Further, The New York Times best-seller found itself on scores of “must-read” summer book lists, including The Hollywood Reporter, Entertainment Weekly, The Wall Street Journal and Publishers Weekly.

“I was just hoping that the book would sell,” she says. “People don’t really believe me when I say that, but there are a lot of good writers whose books haven’t sold. The publishing industry is tough.”

Teddy Wayne, MFA ’07

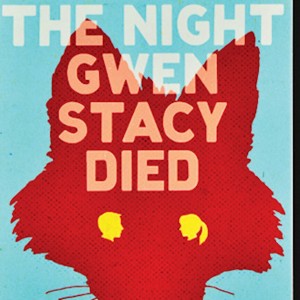

Examining late capitalism and greed

Teddy Wayne’s first novel did not get published. An excerpt from it, though, helped him get admitted to Washington University’s MFA Program.

Halfway through the first year of graduate school, he started writing Kapitoil, which his agent tried but failed to sell during Wayne’s third year. Close to giving up on it, Wayne got some good advice, revised the book, and then sold it in 2008.

“If it had not been published, I probably would have looked into alternative careers,” Wayne says.

Yet, work out it did. For Kapitoil (Harper Perennial, 2010) — hailed by the Boston Globe as “one of the best novels of [this] generation” — Wayne was awarded the 2011 Whiting Writers’ Award and was a runner-up for the 2011 Pen/Robert W. Bingham Prize, among a spate of other awards.

In the novel, Wayne tells the story of Karim Issar, a young Qatari computer programmer relocated to Wall Street, and his struggle with morality and profit.

In 2013, Wayne followed up with The Love Song of Jonny Valentine (Free Press, 2013), about an 11-year-old pop music megastar. In The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani wrote that it’s “more than a scabrous sendup of American celebrity culture; it’s also a poignant portrait of one young artist’s coming of age.”

“Both books are about late capitalism, Kapitoil in more overt ways with the world of finance,” Wayne says. “Then The Love Song of Jonny Valentine is about the pop culture world, which is heavily built around commerce and as a series of products rather than objects of art. The artists themselves are more like employees on an assembly line than they are individuals separated from the production.”

In writing both novels, Wayne drew on his decade-long, intimate experience in journalism and satirical writing. “A lot of Jonny’s observations of the music industry are applicable even to how publishing works,” he says.

Rachel Hartman, AB ’94

Fantasizing of scholarly dragons

A “laboratory for thought experiments” — that’s how Rachel Hartman, AB ’94 (comparative literature), describes fantasy literature.

In her debut novel, Seraphina (Random House, 2012), Hartman creates the kingdom of Goredd, where dragons and humans have endured peace for four decades, but have mistrusted one another for all time. In this medieval-esque world, dragons fold themselves into human form and, with superior logical reasoning, serve society as scholars and teachers. Humans, forever struggling with their complex emotions, often act colder than their reptilian counterparts.

At the story’s center, a young female protagonist, Seraphina, tries to bridge the two worlds through music, even as political intrigue and murder threaten to blow up the peace. She hides a secret, however, that could further inflame the smoldering situation.

According to Hartman, author Terry Pratchett, of the Discworld series, opened her eyes to what fantasy could do. “It doesn’t have to be escapist fluff,” she says. “Fantasy can encompass any issue; it’s especially good for subjects considered difficult or controversial in other arenas: racism, sexism, religion, politics.”

Hartman apparently learned well from Pratchett, because she was recognized with the 2013 William C. Morris Debut Award, which celebrates an unpublished author who has made a strong literary debut in writing for young adult readers.

The Morris Award, one of many Seraphina garnered, seemed anything but likely for Hartman a few years ago. “It took me nine years to get Seraphina published, but I had some bad luck,” she says, “an editor quit, and I changed publishers mid-book.”

Revising a sequel now (she is under contract for two), Hartman says writing the second book has been more difficult in some ways.

“Now, I am conscious of having thousands of readers I can disappoint. [Yet] I am finally getting back to loving the work for its own sake,” she says. “It is crucially important to love the process; nothing else is guaranteed in this business.”

Rick Skwiot is a freelance writer based in Key West, Fla.; Terri Nappier is editor of this magazine.