Most college students have a plan. Sometimes it’s as sure and straight as a highway. Other times it’s a mere adumbration. But students know something of what they want to become and study what will help them on their way. Then life intervenes, and they don’t get into medical school; or after four years of study, they realize that they don’t like their field or they always wanted to do something else less practical. These five graduates prove that even if your best-laid plans do go astray, a WUSTL education is about more than career training. At Washington University, students learn who they are and develop the courage to walk their own paths, no matter how little traveled they may be.

The Russian literature major who became an artist

Erika Simmons, AB ’06, pulled the brown cassette tape out of its plastic casing. The spools whirred as the tape puddled on the floor in a curly pile. She knew she wanted to create a piece of art, but she wasn’t sure what. When she saw the brown curls, she thought of rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix. From there, everything fell into place.

Simmons grew up in Orlando, Fla. Her father was a professional motorcycle racer, and her mother was a costume designer for Universal Studios. Simmons moved to St. Louis when she was 18, and since Washington University was the best school in the area, she applied and was accepted.

At the university, she majored in Russian, which she had started teaching herself when she was 13. “I wanted to be a mafia princess,” Simmons jokes. In her spare time, she waited tables to put herself through school.

In 2008, she saw a pile of cassette tapes … on top of a blank canvas. “That’s when the idea struck me: ‘What ghosts could be hiding in those machines?’”

— Erika Simmons, AB ’06

After graduating in 2006, Simmons moved to Atlanta to take care of her father. A year later, she saw the coffee-table book Masters of Deception: Escher, Dali & the Artists of Optical Illusion, which included pictures from artist Ken Knowlton.

“When I saw Knowlton’s artwork, suddenly, everything clicked. Art wasn’t just for decoration,” Simmons told CNN in 2010.

She particularly loved his portrait of Albert Einstein made entirely from dice. “He’s referencing not only the famous quote, ‘God does not play dice with the universe,’ but also making a subtle statement about the meaning that arises out of the system of empty data,” Simmons says. “We see a face in the dice because our minds make sense of the patterns.”

Simmons started experimenting with her own metaphorical images, and she tore up whatever she could find around the house, but nothing resonated. Finally, in 2008, she saw a pile of cassette tapes she had placed on top of a blank canvas. “That’s when the idea struck me: ‘What ghosts could be hiding in those machines?’”

As Simmons worked on the Hendrix portrait, she knew she was onto something. Online, she asked for old media: VHS tapes, film reels and more cassettes. She began creating portraits of everyone from Audrey Hepburn to The Beatles out of the material that made them famous.

Her image of Beethoven made from his sheet music was featured on “The Huffington Post.” Ripley’s Believe It or Not! bought several of her pieces, and she has been featured in magazines such as British GQ, Details, Wired and The New York Times Magazine.

In 2010, just two years after creating her first portrait, Simmons’ work inspired pop artist Bruno Mars’ video “Just the Way You Are,” which features animated images made from cassette tape. More recently, Simmons created the official artwork for the 2013 Grammy Awards — the iconic Grammy phonograph, spun from a spool of half-inch studio recording tape.

“In a sense,” Simmons says, “it is totally improbable that a waitress with no art training can make an impact. But, on the other hand, I think you don’t have to leave home to have a good idea. If you have something of value to offer, success will find you.”

The chemical engineer turned-restaurateur

In 1952, Marvin Gibbs, BSChE ’56, DSc ’60, had it all figured out. The St. Louis native had gotten scholarships to Princeton and MIT, and though he still wasn’t sure where he’d go, he knew that if he went to Princeton, he’d study business or law; if MIT, he’d study engineering.

All that changed when one of his father’s service stations burned down. He knew then that his family could no longer afford to send him away to school. Yet, Gibbs had not applied to any area universities. So a few weeks before classes were scheduled to begin, he walked into Washington University’s admissions office and asked for admission — and a scholarship.

It worked, though the scholarship was contingent on his ability to earn good grades.

“There was McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King. Trying to compete against the big boys, who had a lot more money, didn’t seem the way to go.”

— Marvin Gibbs, BSChE ’56, DSc ’60

At the university, Gibbs decided on chemical engineering as a major, giving up sports to buckle down and study. To save money, Gibbs lived in the maid’s quarters of a mansion near campus, which had “more windows to wash than Carter had liver pills,” he says. He stayed there rent-free in exchange for doing odd jobs around the property.

Gibbs earned a bachelor’s degree in 1956 but stayed on for his graduate work. During summers he worked for Monsanto, and when he graduated from Washington University with a doctorate in 1960, the company offered him a job.

Gibbs liked Monsanto, but “my thinking was that large blue-chip companies can, at some point in time, fall into a deep hole,” he says. Plus, his brother-in-law, Clint Tobias, was looking for a job. “So we decided to start something together,” along with a third partner whom they later bought out.

The partners opened a roast-beef-sandwich shop in Ballwin, Mo., and named it Red Lion Beef House. They quickly realized they couldn’t trademark the name since Red Lion was already a motel chain. So, they changed the name to Lion’s Choice.

“Back then there weren’t as many burger stores as today,” Gibbs says. “But there was McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King. Trying to compete against the big boys, who had a lot more money, didn’t seem the way to go.” While there was some competition in roast beef, notably Arby’s, Gibbs and Tobias were convinced they could make a standout sandwich.

“To this day, all of our beef is whole-muscle top round. We get it fresh. It’s not frozen,” Gibbs says proudly. Subsequently Lion’s Choice caught on, and within two years the co-founders opened a second location in Creve Coeur, Mo.

During the early years, Gibbs occasionally worked the fryer on weekends or did landscaping. Tobias acted as general manager. And while Gibbs also served as company CEO, he never left Monsanto. He went on to a satisfying career there, working until his retirement in 1991. As Monsanto began exiting the chemical business in deference to agricultural and pharmaceutical products, Gibbs segued full time to Lion’s Choice, where he helped grow the company to where it is today.

Lion’s Choice now has 8 franchise and 15 corporate stores, and it is a highly recognized brand across St. Louis. But, according to Gibbs, none of it would have been possible without the university.

“I’ve always appreciated that Washington University gave me the opportunity — I was going to say at the 11th hour, but it was more like 5 minutes to midnight — to obtain the education that enabled me to go forward.”

The architect who went to Hollywood

As Neil Wade, AB ’02, finished his junior year in architecture, he noticed a difference between himself and his Givens Hall classmates. “It was obvious that everyone around me loved what he or she was doing,” Wade says, “but I wasn’t in love with it.”

Growing up in Tulsa, Okla., Wade had always enjoyed drawing. His art teacher encouraged him to pursue architecture, a practical application for his talent. He followed his teacher’s advice, but Wade actually loved comic books and Japanese animation.

While at Washington University, though, he heard about the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program, which sent native English speakers to Japan to teach. Wade applied during his senior year and was accepted; he figured he’d spend his first year after college away from architecture to determine what he wanted to do long term.

“From the time I arrived in L.A., I knew that animation and entertainment were my world. I just wasn’t exactly sure where I fit into it.”

— Neil Wade, BArch ’02

After graduating in 2002, Wade went to Fukui, the third least populated prefecture in Japan. While there, he fell in love with the culture, the language and the country. He applied to stay two more years and then realized what he wanted to do. “I remember looking at a billboard for one of the animated films there and saying to myself: ‘That’s what I want to do,’” Wade says.

When he returned to the United States from Japan in 2005, Wade researched his options and applied to three art programs in Los Angeles. Then, without knowing if he was accepted, he packed up his car and moved to Hollywood.

It was in L.A. that Wade found out he’d been rejected by all three schools. At the time, his roommate moved out; he lost one of the three jobs he’d cobbled together to make ends meets; and he ran out of money.

“I was about to leave, but one of my best friends said, ‘You can go back to Oklahoma and never do animation, or you can stay here and figure out another way,’” Wade recalls. “It had never occurred to me that there was another way.”

Wade enrolled in a graphic design program at Pasadena Community College to be eligible for internships and applied to Nickelodeon for one in cartooning. In January 2009, he started as a production intern at Dora the Explorer.

“I found out there that I actually enjoy production,” Wade says. “And then my first job made me love production over the artwork.” A friend knew someone at Family Guy and passed Wade’s résumé along. In October 2009, Wade started there on the production team, responsible for assigning tasks to animators and making sure design elements meshed.

“It was very hectic and very challenging,” Wade says. “But I wouldn’t give it back for the world.” He also remained on good terms with Nickelodeon; in fact, they called him whenever a job opened up.

“At Wash. U., I learned how to manage relationships and how to have a voice for myself,” Wade says. “Now, in the world of entertainment, those skills have kept me moving forward.”

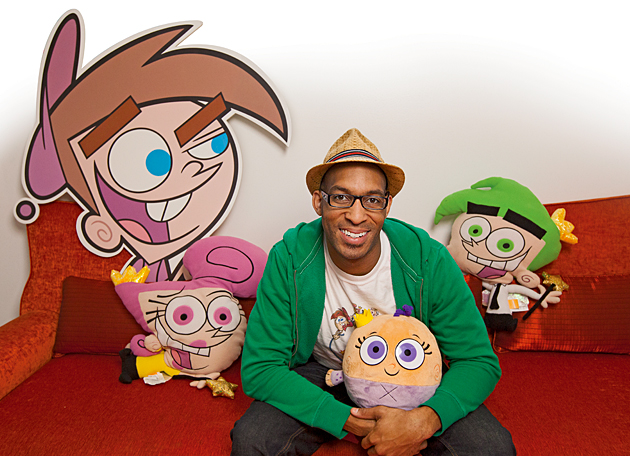

Thanks to his connections at Nickelodeon, Wade now works at Fairly Odd Parents, overseeing production from script to final design. And he gives back by mentoring interns as well.

“From the time I arrived in L.A., I knew that animation and entertainment were my world,” Wade says. “I just wasn’t exactly sure where I fit into it. But the idea of moving backward was more terrifying than anything, so I just kept moving forward.”

The Poli-Sci major who flourished as an actress

In fifth grade, Pooja Kumar, AB ’01, played Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew. “I played the guy role,” she says, “and that’s when I knew I had to go into acting.”

Her mother introduced Kumar to Indian classical dance at an early age, and Kumar enjoyed performing. While growing up in St. Louis, she acted in musicals such as Oliver, Grease and Annie at the Muny, a well-regarded summer theater company.

When she was 18, Kumar auditioned to dance during show interludes at Miss India Illinois, a regional beauty pageant. The organizers wanted her to be a contestant, and, though she’d never done a beauty pageant before, Kumar agreed. “I thought it’d be great to meet other women who were interested in education and doing something for their community,” she says.

“The university gave me a sense of myself. It did actually create my voice.”

— Pooja Kumar, AB ’01

Then she won. She went on to the national Miss India USA competition and won that too.

“Doors opened up in India after that,” Kumar says. “But coming from a South Asian family, entertainment was not the field that one was supposed to aspire to.”

So Kumar enrolled at Washington University, where she studied political science. And, as long as she was getting a good education that offered other career possibilities, her parents also supported her acting pursuits.

Kumar entered a competition sponsored by Amitabh Bachchan Corp., an Indian entertainment company looking for up-and-coming stars to launch. Sixty thousand people applied, and Kumar was one of only 10 winners.

“That gave me a sense of credibility and the drive,” says Kumar, who then took a year and a half off of school to pursue acting opportunities in commercials and TV. In 1997, she landed her first leading role in the feature film Kadhal Rojavae, a movie in Tamil. While Kumar is fluent in Hindi, she doesn’t know Tamil; therefore, her lines had to be written out phonetically. “Basically it was memorizing gibberish,” recalled Kumar in an interview.

Afterward, she returned to Washington University and finished her studies, even interning for U.S. Rep. Jim Talent in Washington, D.C. In 2001, she moved to New York and studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts to hone her craft. She also wanted to work in the United States, where she saw a dearth of South Asian actors.

Her first American movie, Flavors, netted her the Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Emerging Actor at the St. Louis International Film Festival. “I was on cloud nine when I got that award,” she says.

Kumar has since been in more than a dozen films in India and the United States and has done television work, such as Law & Order: SVU and Bollywood Hero, a 2009 miniseries on IFC, in which she plays the love interest of Chris Kattan. This year, Kumar was in the film Vishwaroopam, an action caper released across South Asia that has become one of India’s top movies, grossing more than $30 million.

Though she didn’t go into politics, Kumar says Washington University still prepared her for her career. “The university gave me a sense of myself. It did actually create my voice,” Kumar says. “I wouldn’t have had one if I hadn’t gone to college.”

The biologist who grew into a businessman

Growing up in New York, Dean Shulman, AB ’77, spent hours in his basement making models of balsa wood, ignoring his mother’s calls for him to come up for dinner. “I was always interested in science and always kind of a tech guy,” Shulman says.

When he enrolled at Washington University in 1973, he wanted to become a doctor. So he followed the pre-med track and majored in biology but was subsequently rejected from medical school. He stayed in St. Louis, however, and worked at Barnes Hospital as a research assistant. But when he got waitlisted for med school the following year, he headed back home to New York.

“I ended up doing what a lot of people did back then,” Shulman says, “I took a sales job.” He worked for Savin Corp., a copy-machine business. Over his seven-year stint there, Shulman rose through the ranks, eventually heading up Savin’s information systems division.

In 2009, Shulman took over Brother’s sewing and embroidery division, “about which I knew nothing. But I knew I wanted to turn this from a hardware business into a fashion business.”

— Dean Shulman, AB ’77

In 1986, after earning a master’s degree in marketing from Baruch College in New York City, Shulman was asked to be the first director of marketing for Brother International, a Japanese company known for its sewing machines and typewriters.

The first device Shulman had to market was the P-Touch, a hand-held label maker. Thinking that the device’s market wasn’t organized types but guys and baby boomers, Shulman bought time on the new, incendiary Howard Stern radio program.

“We got hate mail all the time,” Shulman recalls. “But that’s what put P-Touch on the map.”

Under Shulman’s guidance, Brother also became an early advertiser on CNN. Shulman bought two weeks of airtime starting Jan. 14, 1991, because the United States was threatening to go to war with Iraq if it didn’t withdraw from Kuwait by Jan. 15.

Iraq didn’t withdraw. “Everybody was glued to their TV,” Shulman says. “Every advertiser wanted to jump in, but, of course, they got pre-empted, and literally all you saw on CNN for two weeks was a P-Touch commercial.”

In 2009, when the head of Brother’s oldest division stepped down, Shulman took it over. The division was sewing and embroidery, “about which I knew nothing,” he says. “But I knew I wanted to turn this from a hardware business into a fashion business.” Shulman, who is now senior vice president and a member of Brother International’s board, partnered Brother with Heidi Klum’s reality TV show Project Runway, which proved a prescient move. Not only are all the show’s sewing machines made by Brother, but Brother also sells the only Project Runway sewing-machine line.

The Project Runway pairing and other Brother sewing-machine innovations have made Shulman the seventh most influential person in the garment-decorating industry, according to Stitches magazine’s 2012 Power 75 list. They also earned him a spot in the Sewing Hall of Fame in 2012.

Shulman says it was his time outside of the classroom at Washington University that helped prepare him for his future. He managed Fat Albert’s, a coffeehouse on the South 40 for three years. “At Wash. U. the classes were great, and all the teachers were great, but for me it was the South 40 experience that really made me love the university. It was intramural football, Thurtene Carnival, Walk In Lay Down Theater showing movies at night, and doing a raid on Fontbonne. It was,” he says, “a wonderful time.”

Rosalind Early, AB ’03, is a freelance writer based in St. Louis as well as assistant editor for St. Louis Magazine.