Two decades have passed since researchers have made new advances in the pharmaceutical treatment of depression. But there may be new hope on the horizon, thanks to researchers at the medical school’s new Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research.

To date, drug investigators have focused on tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which tweak the balance of the brain’s neurotransmitters, in turn controlling mood, pain and other sensations. The familiar list of brands includes Paxil and Prozac.

Although current medications are helpful, many have major limitations in terms of their effectiveness and potential for negative side effects. And often, psychiatric drugs do not target the fundamental mechanisms in the brain that contribute to illness.

That means millions of people aren’t getting the help they need. It’s estimated that 5–10 percent of the adult U.S. population suffers from major depression. Within that group, 30–40 percent of individuals have either a partial or no response to current treatments. “Given a population of over 300 million in the U.S., this means there could be 5–10 million or more individuals with refractory forms of depression in need of treatment,” says Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobiology and head of the Department of Psychiatry at the Washington University School of Medicine. “These are staggering numbers.”

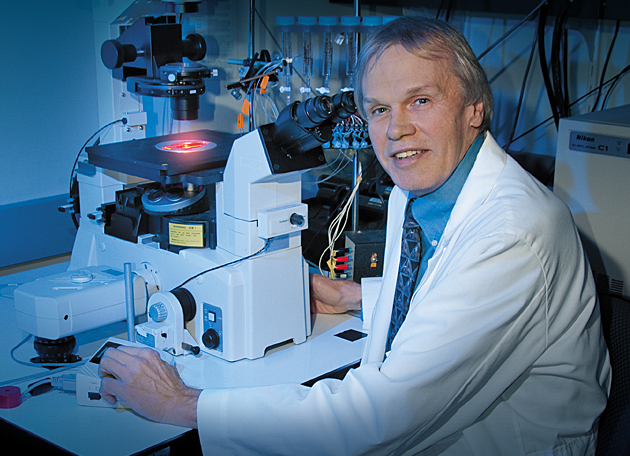

Taking an entirely different path, researchers at the School of Medicine are investigating a relatively new line of research on neurosteroids, which have not yet been targeted by current drug therapies.

Depression costs the U.S. economy $80–100 billion per year in terms of health-care costs, death and lost productivity. It is among the leading contributors to disability and is the leading cause of suicide, which claims the lives of 30,000 people every year. Further, many end-stage illnesses — heart and lung disease, stroke and cancer — are related to alcoholism, nicotine dependence, drug abuse and other psychiatric problems.

Taking an entirely different path, researchers at the School of Medicine are investigating a relatively new line of research on neurosteroids — brain chemicals involved in behavior, stress, memory and depression — which have not yet been targeted by current drug therapies.

Unlike most of the body’s potent steroids, which are made in the sex glands, neurosteroids are synthesized in the brain. “During conditions of acute stress, neurosteroids help to regulate nerve cell function in local regions of the brain and, in turn, in key neural circuits that underlie emotion, motivation and cognition,” Zorumski says. But under conditions of chronic stress, as occurs in depression, production of these neuromodulators is diminished, which may contribute to or worsen mental dysfunction. “While we don’t fully understand how neurosteroids are downregulated with chronic stress, the dampening of neurosteroid-mediated modulation suggests that treatments that help to replenish or replace neurosteroids could be effective,” he says.

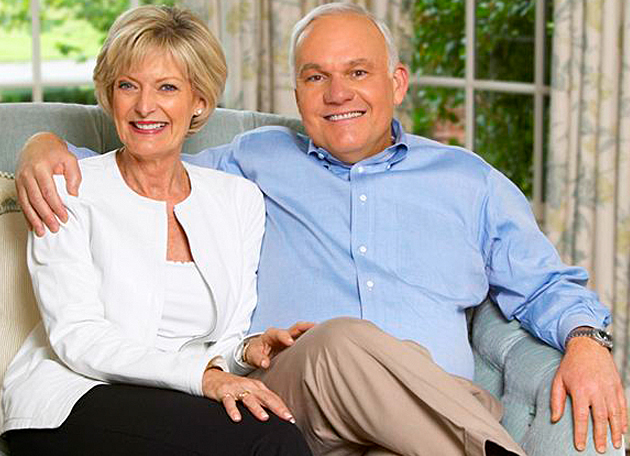

Research into the potential for novel treatments of depression and other stress-related conditions, including neurosteroids, is the first order of business for the new Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research, established with a $20 million gift from Andrew and Barbara Taylor and their family. “The initial goal is to support the efforts of a highly integrated and hierarchical group of scientists in an effort to develop neuroactive steroids as therapeutic agents for psychiatric and neurological disorders,” Zorumski says. “Over time, we hope to expand the institute to include other scientists from the Washington University community in an effort to develop other novel pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches for treating a wider-range of psychiatric disorders, including those occurring in children and adolescents.”

Ultimately they hope to develop new drug therapies for mood disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, alcoholism, sleep disorders, chronic pain, epilepsy and neurodegenerative illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease.

For those suffering from mental dysfunction and unassisted by current medications, it’s about time.