Where else can one see a diamond glow under black light, look at a meteorite from Mars, compare mastodon to mammoth teeth, see sand fused into glass by the atom bomb test at Trinity, or watch angry red ring appear on a monitor when the basement seismometer picks up a distant quake?

To celebrate the naming of Rudolph Hall, eight years after it opened, the following are several stories about the building’s construction and its contents. (To learn more about the May 4 dedication ceremony paying tribute to Scott and Pyong Rudolph and featuring Bill Nye, “The Science Guy,” visit the university’s Newsroom.)

1. Rudolph Hall is an optical illusion.

One of the instructions issued by the Board of Trustees for the new building was that it was not to overshadow the iconic Brooking Hall from any vantage point.

“They shrank it vertically. The east-west wings step down to the street, and the south wing, toward Brookings, is shorter than the north wing.”

—Robert Osburn

The architects used every trick in the book to make it look smaller,” says Glenn R. “Robert” Osburn, laboratory administrator, geologist, museum curator and spelunker.

“They shrank it vertically. The east-west wings step down to the street, and the south wing, toward Brookings, is shorter than the north wing.”

For these reasons, Rudolph Hall appears to nestle into the foot of the hill Brookings Hall crowns.

2. Early design exuberance turns to practicality.

In the early designs for the building, the library was a separate little castle to the south of the main building and joined to it by an arch. However, the first round of cost estimates knocked out this Gothic fantasy.

3. Seismometer picks up quakes from across the world.

Rudolph Hall sits on feet in a layer of shale beneath the building, but the crew drilled to bedrock for the seismic pier, a freestanding pillar of unreinforced concrete in the building’s capacious basement. The pier transmits ground motion with minimal distortion to the seismometer that sits on top of it. The seismometer signals are then sent to a computer display on the second floor, a favorite spot for television interviews of seismologists after major earthquakes.

Many visitors assume that the monitor is somehow fed from a remote site, but it is instead recording what is happening directly beneath the building itself.

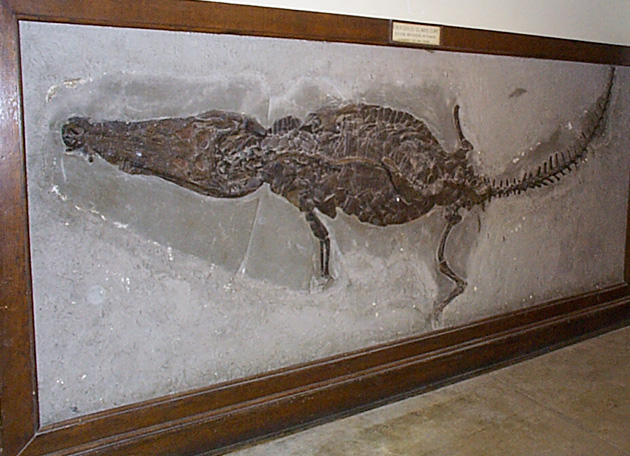

4. Building houses huge crocodile, originally from downtown campus.

Mounted on the walls of Rudolph Hall are many spectacular fossils of creatures long extinct, some of which come from famous German lagerstätten, or fossil beds, where animals were preserved in exquisite detail.

The biggest fossil in the building is the 12-foot crocodile on the first floor. It was collected some time in the 1800s by Gustav Hambach, a German immigrant who became head of the geology department in 1887. He remained department head until he was forced to retire in 1906, after he was run down by a fire engine in downtown St. Louis the day after Christmas in 1905. He lived for another 20 years.

5. Sea urchins discovered during Famous-Barr excavation are on view.

The spineless sea urchins on the second floor of Rudolph Hall were discovered during the excavation for the Famous-Barr department store in downtown St. Louis. They date from the Mississippian subperiod when most of the mid-continental United States was a salty inland sea and St. Louis was under water.

6. Amethyst filled geode was rediscovered during move from Wilson.

Geology, it has been said, has accumulated much more loot than any other department at the university, much of it on display in the Matthew A. Grossman Museum on Rudolph’s first floor.

Several interesting geological specimens, including a large geode, sat for years on the flared bottom step of the staircase in Wilson Hall, geology’s former home, gathering dust. When the geode was moved over to Rudolph, Osburn took a hose to it and discovered it was lined with amethyst.

He later learned from Pyrite Deposits of Missouri that our geode is the second-biggest geode ever found at the open pit iron mine in Sullivan, Mo. Apparently a farmer somewhere has a bigger one in his yard.

7. Many of the museum specimens are gifts from people who just like rocks.

Almost every specimen in the museum has a story.

“We took a photo of the rock, because we thought that was all we were going to get. But Nichols walked in again another day, set the fossil on my desk and said, ‘If I gave that to you guys, could you do anything with it?’ And I said, ‘It would go into the case today.’ And it did.”

—Robert Osburn

For example, while the building was going up, the construction superintendent Eric Nichols said to Osburn, “I’ve got a fossil I’ve had ever since I was a kid. I wonder if you’d look at it and tell me what it is.”

It turned out Nichols had a beautiful fossil. “I was just speechless because people don’t just walk in with things of that quality,” Osburn says.

Harold “Doc” Levin, PhD, emeritus professor of paleontology, identified the fossil as two species of crinoids.

“We took a photo of the rock, because we thought that was all we were going to get,” Osburn says. “But Nichols walked in again another day, set the fossil on my desk and said, ‘If I gave that to you guys, could you do anything with it?’ And I said, ‘It would go into the case today.’ And it did.”

8. Scott Rudolph donated 33 boxes of specimens to the museum.

In his remarks at the dedication ceremony, Scott Rudolph, now a member of the WUSTL Board of Trustees, said that he became interested in geology and mineral hiking while exploring the landscape of Canyonlands National Park in Utah.

The week of the dedication he sent 33 boxes of mineral specimens to the Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences (E&PS). Six specimens are on display in the first floor museum as of this writing, but Rudolph says the geologists haven’t found “the good stuff” yet.

9. The rover in the atrium is a NASA publicity model.

In addition to the E&PS department, Rudolph Hall is home to the McDonnell Space Science Center.

Taking pride of place in the building’s atrium, deliberately designed as a gathering space, is a publicity model of the Mars Exploration Rover (MER), nabbed for the department by Ray Arvidson, PhD, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and deputy principal investigator on the (still-ongoing) MER Mission.

10. Featured photo shows hazards of field geology.

The erupting volcano on the wall in the rover atrium is no stock photo. It is one of many photographs made by a team of WUSTL researchers led by Doug Wiens, PhD, professor of geology and chair of the earth & planetary sciences department, when they were installing seismometers in the Mariana Islands in 2003.

The researchers installed a broadband seismic station atop what they thought was a dormant volcano on the remote island of Anatahan. However, four days later, as they were returning to base, they saw lightning over the island at night and in the morning a towering pillar of ash and steam.

11. Art and science jostle in a mural.

The murals in the atrium are oil paintings on canvas designed by display consultants from photographs the geologists provided.

In the mural, the Moon, Mercury and Venus, vastly enlarged, float above the snowscape. “It doesn’t seem to bother other people as much as it does me.”

—Robert Osburn

The foreground of the one mural replicates the background of a photo Randy Korotev, PhD, the department’s meteorite expert, made while hunting for meteorites on the Antarctic ice. It shows the Lewis Cliff ice tongue, where more than 1,900 meteorite stones have been collected, including a Martian meteorite.

In the mural, the Moon, Mercury and Venus, vastly enlarged, float above the snowscape. “It doesn’t seem to bother other people as much as it does me,” Osburn says.

Korotev considers it “space art” for which different standards apply.

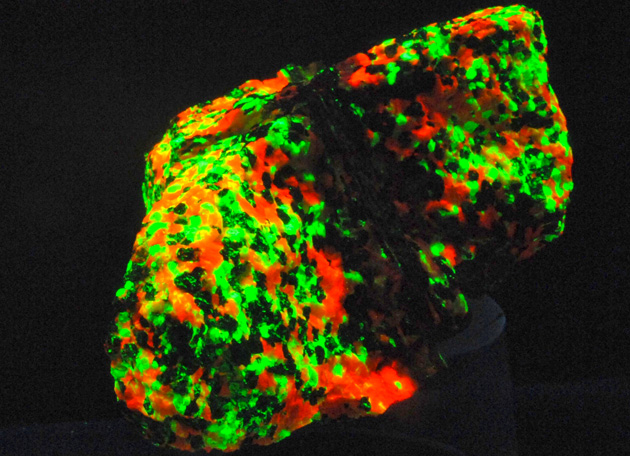

12. Rocks that glow are the most popular specimens in the building.

The most popular display in Rudolph Hall, provided you can find it, is the one with the fluorescent rocks.

Some of the specimens in the display belong to Jill D. Pasteris, PhD, professor of earth & planetary sciences, who was allowed as a graduate student to enter one of two New Jersey mines famous for fluorescent rocks and bring out as many as she could carry.

“I think everyone is attracted to fluorescent colors, since they are different from the colors we are used to seeing,” Pasteris says. “But it’s actually the element magnesium, not zinc, that makes the rocks fluoresce.”

Osburn trawls gem and mineral shows looking for fluorescent minerals to complete the display. This turns out to be a bit trickier than one might think because most minerals that fluoresce, don’t always fluoresce — even fluorite, the mineral that gave its name to the phenomenon of fluorescence.

Osburn has a story about that. One day a visiting diamond merchant walked in his office and demanded to know why there was no diamond in the display. Osburn said they didn’t own one and, anyway, he didn’t know they fluoresced. The merchant then donated a diamond.

“The diamond in the case,” Osburn says, “is not a very big or impressive diamond, but it fluoresces. Other diamonds you put in there don’t do anything. My wife has a little three-stone diamond ring, and only one of the three stones fluoresces if you put it in the case.”

13. Some people ask that Pluto be removed from the planet walk.

The same care was lavished on the approaches to Rudolph Hall as on its interior.

The eastern approach features the “planet walk,” a scale model of the Solar System that captures the relative spacing of the planets, represented by bronze disks set in the pavement. The Sun is just outside the building’s door and Pluto nearly in Throop Drive.

And, yes, the occasional know-it-all drops by Osburn’s office to ask that Pluto be removed now that it has been demoted as a planet.

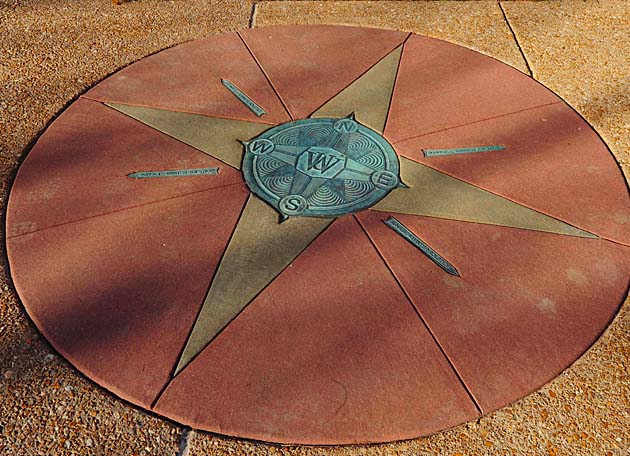

14. Aligning the compass rose wasn’t easy in the days before GPS.

Inlaid in the pavement on the western side of the building is an eight-pointed compass rose of the sort found on treasure maps. It, too, has a story.

The compass points to true, also known as geographic north, located by finding magnetic north and adding the known deviation of true from magnetic north.

The site superintendent thought he had lined up the compass right and wanted Osburn to check it before the concrete was poured into the forms. But there were 50 pounds of rebar within five feet of the superintendent’s compass.

Rebar, which is made of steel, can easily be magnetized and might — who knew — be throwing off the compass reading.

Osburn and Robert E. Criss, PhD, professor of earth & planetary sciences, set to work to find magnetic north. At one point they thought they’d have to do a Sun shot to get it right. Yet, they eventually discovered that the superintendent was off by only 20 degrees!

Criss and Osburn knocked the frame into alignment with a sledgehammer.

15. The rock walk reproduces Missouri stratigraphy.

Tucked into a steep hill between Rudolph and Compton Halls is the “rock walk,” which Osburn calls an imperfect attempt to show off the rocks of Missouri in stratigraphic order.

The passerby slowing to climb the hill has time to contemplate the rocks, and perhaps to notice the petrified ripples in one of the sandstone slabs.

When that slab arrived, Osburn delegated to a graduate student the duty to examine both sides of the rock while it was still suspended (the rocks were lifted into place by a crane whose arm extended through the crack between Compton and Rudolph halls) to see if there were ripples. The student reported there were none, and so the rock was lowered into place.

The toast always falls butter side down. Of course, there were ripples, and, of course, they were face down. The sandstone block has since been lifted and flipped.

“They’re not great ripples,” Osburn says, “but they’re definitely ripples. In the student’s defense, he is a planetologist.”

Diana Lutz is the senior science writer in the University News Service of the Office of Public Affairs.