Relationships. Connection. Interdependence. For Michael A. McClure, AB ’91, and Ursula Emery McClure, AB ’92, these concepts form the foundation of their lives — from their marriage to their architectural practice to their shared research.

They ponder tectonics — the theory, art and science of building, and the relationship of the parts to each other and to the whole.

They work to use successful adaptations of the past to inform the innovations of the present, combining old and new rather than choosing between them.

For the McClures, the parts that constitute the whole are culture, ecology, geology, infrastructure and more. They work to use successful adaptations of the past to inform the innovations of the present, combining old and new rather than choosing between them. They also take the lessons learned from Louisiana’s unique culture and geography and apply those principles globally.

At the heart of their work is the “terra viscus,” a “super-saturated condition, never completely solid or liquid. It consists of geological, economical, cultural and ecological conditions that interweave and overlap.” Their exploration and articulation of this analytical methodology won them the coveted Rome Prize in Architecture, as well as “a place at the table” in the national discussion on how to rebuild New Orleans and manage wetlands in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Convergence

Ursula speaks enthusiastically, her observations coming so quickly that they spill from her lips in spirited succession, punctuated by wry humor. In contrast, Michael speaks more deliberately, his phrasing fully formed before utterance.

Ursula’s father is noted medieval scholar Kent Emery Jr. She and her five siblings, all named after medieval saints, were uprooted several times as his career progressed, and there was never any doubt that they would pursue academic degrees. Michael, hailing from a small Oklahoma farm town, “dreamed big” of college in the big city.

Despite these differences, they clearly share professional passion, curiosity and ideals.

“So much of who you are as an architect has to do with how you were educated,” Ursula says. “We both went to Washington University for undergraduate architecture, which is not a professional program. That means we went there already knowing, somewhere in our minds, that we wanted to have a research practice.”

“We’re proud of the fact that we have liberal arts degrees from Washington U.,” Michael says. “That broad-based, multidisciplinary education informs our work as architects. Architecture is part of a larger whole. It comes out of all the other disciplines of the humanities. Architecture is a reflection on those things.”

“We went to Washington U. together,” Ursula adds, “but we didn’t know each other there, which is weird. We didn’t actually meet until we went to graduate school at Columbia.”

“We went to Washington U. together,” Ursula adds, “but we didn’t know each other there, which is weird. We didn’t actually meet until we went to graduate school at Columbia.” There, the two found out they’d had the same teachers and many of the same friends at Washington University, and that both of them knew they were going to do something different than just be a professional architect.

The couple married in 1995. After graduating from Columbia — Ursula in 1995 through an accelerated program and Michael in 1996 — they practiced their craft in New York City. Ursula worked for a midsize firm that built public schools. Michael worked for two boutique firms before becoming a project manager at Robert A.M. Stern Architects.

Then, in 1999, they made the move that changed everything: accepting teaching positions in Louisiana and transplanting their firm, emerymcclure architecture.

“Isn’t it funny we both chose this liberal arts school in St. Louis that greatly affected the way we think?” Michael asks. “And then we went to a school that was in many ways its opposite for graduate work, and that changed the way we think, separately. Then we got together, with the formation of our thoughts, separate but really coming from the same history. Together we decided to move to Louisiana, and that was a huge paradigm shift.”

Synergy

“I guess the most important thing to understand is that we are architects; we have a firm; and we build small projects,” says Ursula, who is the Emogene Pliner Associate Professor in the School of Architecture at Louisiana State University. “We also do what’s called ‘research practice’ that’s based on speculative architectural questions, which means we are imagining and designing ideas for discussion.”

Ursula further explains that their teaching and their work are all integrated, so the research that they do and talk about affects the smaller built works that they do. They also choose projects that work toward their research.

“We also do what’s called ‘research practice’ that’s based on speculative architectural questions, which means we are imagining and designing ideas for discussion.”

“We have commissions, but they’re often commissions for ideas, not actual projects,” she says. “People commission us to think about stuff.”

The research practice has a great tradition in architecture but is rare these days, says Michael, associate professor in the School of Architecture at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

“For the first few years after we moved down to Louisiana, we were writing and publishing critical theories about how what we saw in Louisiana fit into the larger world,” he adds. “That’s where the term ‘terra viscus’ came out, as a way of understanding the issues of how we were building things. It’s a way of thinking about culture, infrastructure, ecology, geology.”

And then the storms came.

Hurricanes Rita and Katrina devastated Louisiana. The McClures decided then that it was time to build upon the ideas they had been writing about and become part of the discussion of what to do in the aftermath.

“Basically, we weren’t satisfied with the either/or discussion that was going on nationally,” Michael says.

According to the McClures, one camp wanted to return the low-lying areas of New Orleans to the natural ecology, and the other side argued that there’s an important culture in the lower 9th ward and those people deserve to live there.

“Our answer was, both sides are right,” Michael continues. “Architects can do more than solving one problem or another. We can actually understand the larger problem and engage in changing the way we think about urbanism and culture and architecture.”

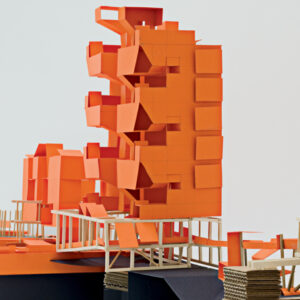

What might a new city look like, embedded in the culture, geography and ecology of the Louisiana coast? This was the essence of NOkat (No Katrina, No Catastrophe, No Category), a search for relevant building techniques in the “terra viscus.”

The McClure’s entry in the 2006 High Density High Ground New Orleans Housing Competition was among the top 20 chosen for display at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. This was followed by NOkat, their design entry for a broad symposium hosted by the University of Texas School of Architecture, which was selected for exhibition at the Venice Biennale 2006. Their intricate designs work with natural systems to include such features as permeable solar-screens, canals, agriculture and multi-level cityscapes that remain deferential toward New Orleans culture and tradition. (Visit www.emerymcclure.com.)

Working with the Coastal Sustainability Studio at LSU, they also have explored solutions that protect the wetlands, while making them more accessible in rural areas hard hit by hurricanes Rita and Katrina.

Harmony

The complexity and clarity of these musings won the McClures the coveted Rome Prize for Architecture and a yearlong stay (along with daughter, Ada, now 8) at the American Academy in Rome, where they were given studio space and resources, fed, housed and nurtured. There, they shared ideas with prizewinners from other disciplines and explored the “terra viscus” of Ostia, the ancient Roman port city whose wetlands — like those in Louisiana — have been radically altered over time through both natural processes and the effects of human occupation.

Primarily, says Ursula, the Rome Prize is the “gift of time,” an opportunity to take a vacation from the distractions of ordinary life and focus completely on intellectual pursuits in order to open your mind for the rest of your career. It gave the couple renewed confidence in the global relevance of their ideas.

“We need to be contemporary because we’re in a contemporary world,” Michael says. “It’s harder to try to move tradition forward. Yet we don’t need to get rid of all the historic typology — that’s how we got here.”

“We need to be contemporary because we’re in a contemporary world,” Michael says. “It’s harder to try to move tradition forward. Yet we don’t need to get rid of all the historic typology — that’s how we got here. The Pantheon in Rome is a place where academics go to study, but tourists from all over the world go there, too. If we could somehow tap into that kind of effect with our architecture, then we’re doing something great.”

Ursula continues the thought: “We don’t think about style. We think about how it operates, not the way it looks. Traditional Southern architecture takes a lot of that into account — climate, lifestyle, sustainability. But we don’t have to mimic or copy that style. What we build must just act in that manner.”

“Here’s the rub,” Michael says, “contemporary architecture doesn’t do that. As a society, we’ve become more concerned with how it looks than how it operates. For example, one of our clients, the Greenes, already had a back porch. But it didn’t act like a porch. On the south side, the sun was always bearing on them. And the porch wasn’t big enough; it wouldn’t allow them to get together and have dinner or do any of the things you would normally want to do on a porch. So our job was to make it act like a porch and not just look like one.”

For the McClures, sustainability must be cultural and economical as well as ecological in order to be relevant. But mostly, they say, their work is about asking the hard questions and negotiating opposing sides.

Michael is teaching in Paris this summer, so soon the McClures will be taking Ada to France. There, they will work on a new article describing the graphic collages their exhibitions are known for.

“We haven’t written before about the intellectual part of this and why we work that way,” Ursula says. “But it’s all part of the process.”

Terri McClain is a freelance writer based in St. Charles, Mo.